MACON, Ga. — A federal judge held the Georgia Department of Corrections in contempt of court in April after failing to correct “draconian” conditions at the system’s highest-level – and "harshest" – prison: the Special Management Unit in Jackson.

But nearly seven years earlier, psychologist Craig Haney walked through the halls of the SMU.

After the contempt order, Haney spoke to 13WMAZ about that visit. What he found "shocked" him.

“As I entered the unit, there were a number of prisoners who were trying to grab my attention – crying out, banging on doors,” Haney said. “I was struck by the desperate condition of the people who were inside the cells.”

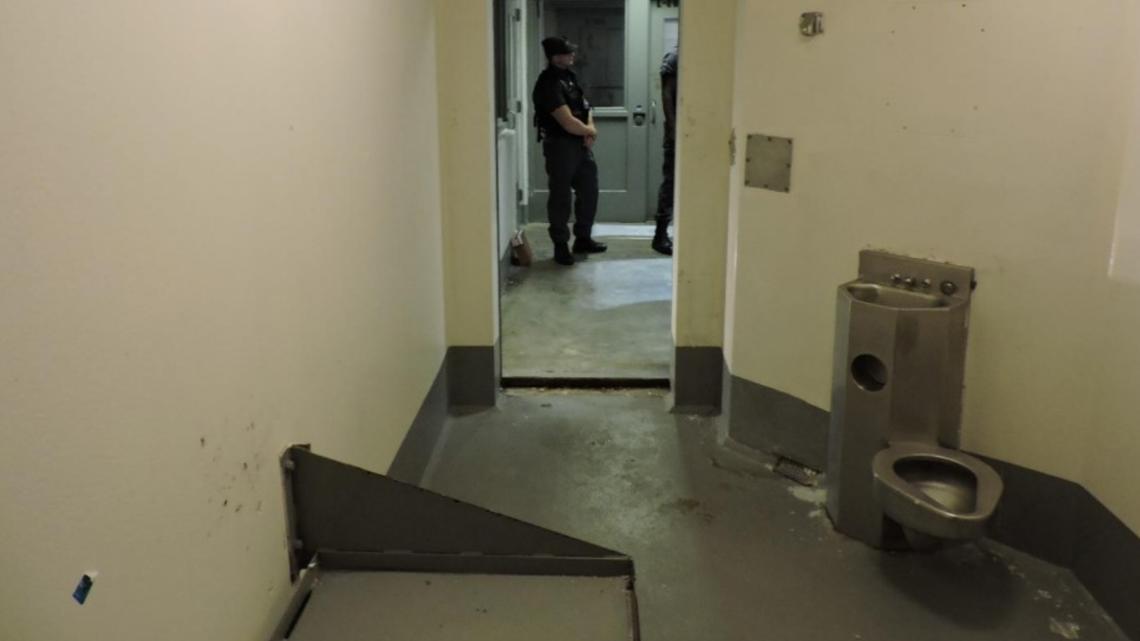

The Special Management Unit, which is nearly 40 miles from Macon, holds the toughest inmates to control.

Inmates were held in solitary-confinement-like conditions, remaining in tiny cells for almost all day. Haney said they received nearly no time out of their cell and few chances to stimulate their brain.

What he saw could only do one thing: “People were being subjected to a significant risk of serious harm, and many of them were clearly harmed by the way in which they were being treated,” he said.

Haney wrote a report that led, in part, to a federal injunction against the Georgia Department of Corrections. The department agreed in 2019 to make changes to bring conditions in line with the Constitution.

But in a 100-page order holding the department in contempt, a federal judge in Macon Marc Treadwell found the GDC blatantly violated nearly every term of the injunction.

“It was evident to the Court that the defendants were figuratively thumbing their noses at the Court and its injunction,” the order read.

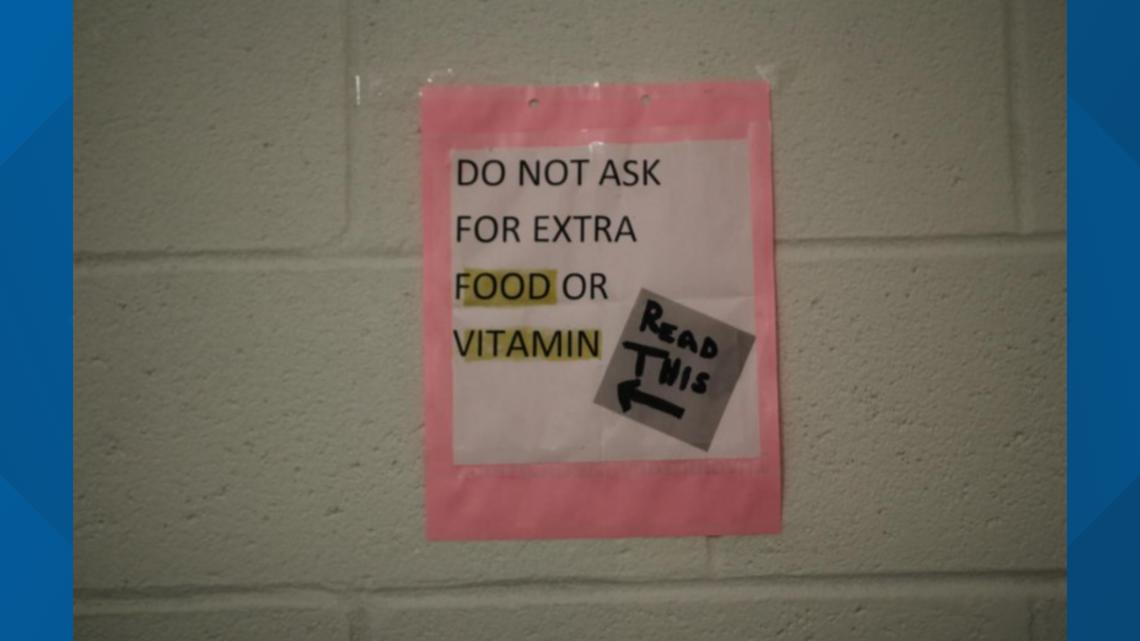

The judge found the GDC didn't provide mandated out-of-cell time, didn't follow admission/release standards and didn't go around the unit with a cart of books. That's among many other requirements.

“It sounded terribly similar to exactly what I wrote about in the report years earlier,” Haney said. “I haven’t seen it with my own eyes. But as I read it, it sounded all too familiar.”

In the aftermath of the contempt order against the Georgia Department of Corrections, Haney recounted his experience at the SMU back in 2017 and what impact the continued treatment could have on the inmates held in those conditions.

“Assuming it was uncharged – or largely unchanged – from the time I inspected it and interviewed the prisoners who were there, [it] could only do more damage,” Haney said.

Scenes of ‘a unit in crisis’

In the seven years since his visit, the desperation that Haney saw still lingered with him. He said his visit was “memorable” – and not for a good reason.

“On every front, they were in truly dire straits,” Haney said

One inmate said they had been in darkness for days since his light was not working; somebody else showed him blood and "an open gash" after attempting to harm themselves moments before; another put up a sign saying “Please help me.”

“These folks were just really in need of help and they made it very clear,” Haney said “I was taken aback by how desperate and distraught they were – and it was consistent.”

According to Haney, that kind of treatment has consequences.

“Nothing good could be expected of a prolonged confinement in a unit like that,” Haney said.

But while inherently unpleasant, he said a few things made conditions particularly mentally damaging: the length of time inmates were being held, having no clear way to get out and systemic mental health issues.

‘Exacerbates the pain’: Solitary confinement ad nauseam

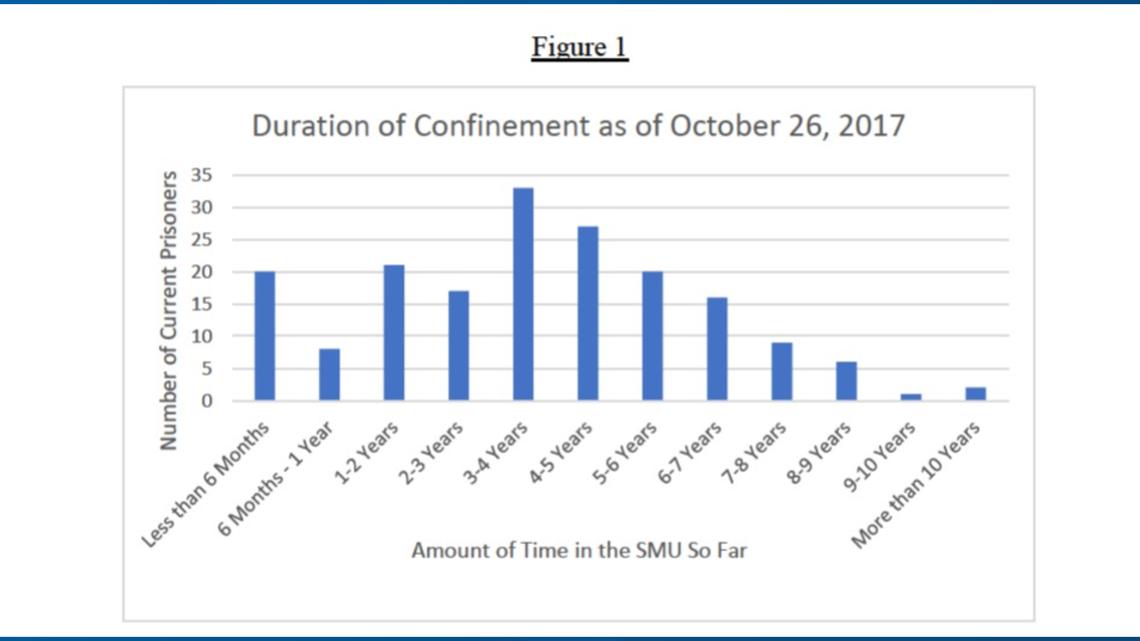

Haney said inmates were being held for years on end in the SMU, and they reported not knowing what they needed to do to move out of the unit.

“When you are in an environment where you are in pain – and these folks were all in pain — not knowing how to end that pain or not knowing when the pain will end, that exacerbates the pain,” Haney said.

After the injunction, the GDC could not keep inmates in the SMU for longer than 24 months unless they met specific exceptions. However, the federal judge found that was repeatedly and systematically ignored.

“In short, solitary confinement had become a final stop rather than an interim rehabilitative step,” Treadwell wrote.

‘A vulnerable population’: Mental illness behind bars

Mental illness among the inmates was another concern. In his report, Haney said nearly a third of inmates were suffering from clear mental illness.

“This is a vulnerable population," Haney said. "Not to suggest it is OK to put anyone in these conditions for long periods of time, but especially the mentally ill.”

The reason behind that is simple, Haney said. He says a person with mental illness held in “severely harsh solitary confinement” is more likely to face “deterioration and harm” than a regular person.

Because of their additional risk, the injunction required mental health assessments before and during inmates' time in the SMU, but the judge found numerous documentation problems and possible forging of documents.

For the people working in the unit, Haney said it seemed that employees became accustomed to the conditions. Because of the lack of outside oversight, he suspects it just became business as usual.

“Nobody said, ‘My word what is going on in this unit? Look at all the number of instances of self-harm…. Look at the people crying out for help, the mental health crisis,’” Haney said. “Not only did we have people in crisis, but this unit is in crisis.”

Why care for the worst of the worst?

While the inmates held in the SMU are the worst offenders – murderers, gang leaders, etc. – inmates don’t lose their constitutional protections against “cruel and unusual punishments” once they get to the prison gates, Haney said.

“There’s a basic level of human dignity they deserve,” Haney said. “The Constitution doesn’t say people are free of cruel and unusual punishment unless someone decides they’re despicable in which case the 8th Amendment does not apply. It applies to everybody.”

But beyond the inmate's “dignity,” Haney says there is a public safety perspective, too. Most inmates will eventually get out of prison.

“All of us have an investment in what kind of person they will be when they get out,” Haney said. “And that investment, it seems to me, ought to include not damaging them.”

To Haney, it raises the question of why prison systems across the country use solitary confinement in the first place.

“Solitary confinement achieves nothing positive… it makes people worse,” Haney said. “That’s not just a problem just for them – it's a problem for all of us.”