MACON, Ga. — Central Georgia has seen it all before: churches, schools and theaters shut down, quarantines, face masks in public.

But it's still never seen anything else like the 1918 Spanish Influenza pandemic.

It killed thousands of Georgians, and in the end, state health officials admitted they just lost count. But compared to other Eastern states, Georgians said they got off easy.

Worldwide, scientists estimate that the flu killed 50 million to 100 million and may have infected half the human race.

But in Macon, the Spanish flu brought unprecedented questions that seem very current today: Who's at risk? What is safe? Should government put safety ahead of commerce? And should the fair go on?

FROM THE TRENCHES TO THE HOMETOWNS

The flu started as just another blow to a world already tired and bloodied by World War I.

Scientists believe it started near the front in France, hitting soldiers in the trenches and the barracks. Then it spread across the globe.

The first U.S. cases were reported in March 1918 at an Army base in Kansas.

Victim often died within several days -- sometimes even developing symptoms in the morning and dying that night.

This flu was also unusual and scary because it seemed to hit healthy young people between 20 and 40 just as hard as the old and young.

Throughout the summer, it jumped from one military base to the next across the U.S., hitting the Northeast especially hard.

By September, it was Georgia's turn.

Late that month, new soldiers at Fort Screven outside Savannah turned up seriously ill.

On Oct. 1, the number of cases at Augusta's Camp Hancock jumped from 2 to 716 in a few hours. By the night of Oct. 5, 50 soldiers were dead.

The camp was quarantined, with 3,000 cases, but the flu had already reached Augusta.

Meanwhile, Fort Gordon outside Atlanta was also under quarantine, with hundreds of cases.

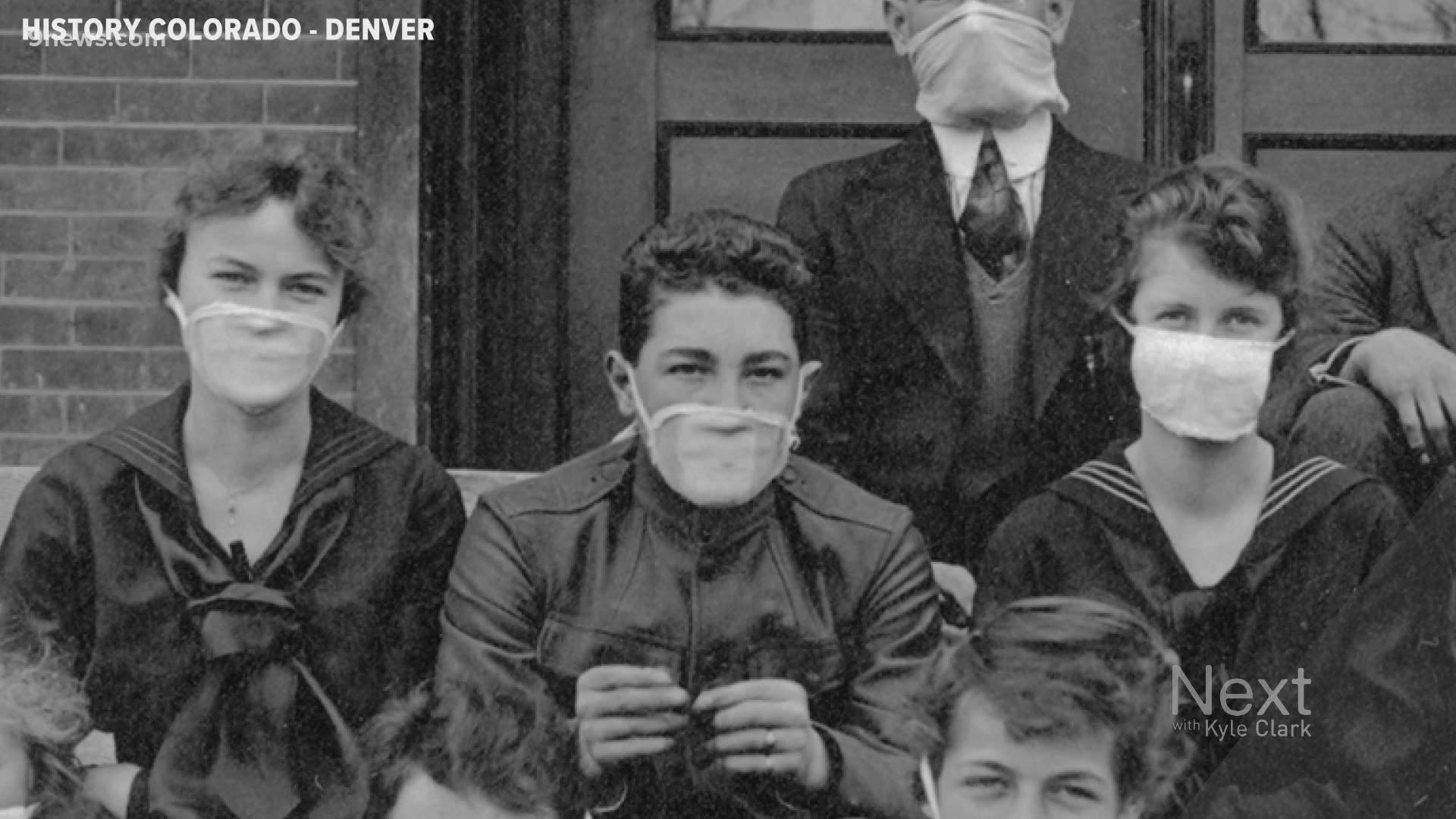

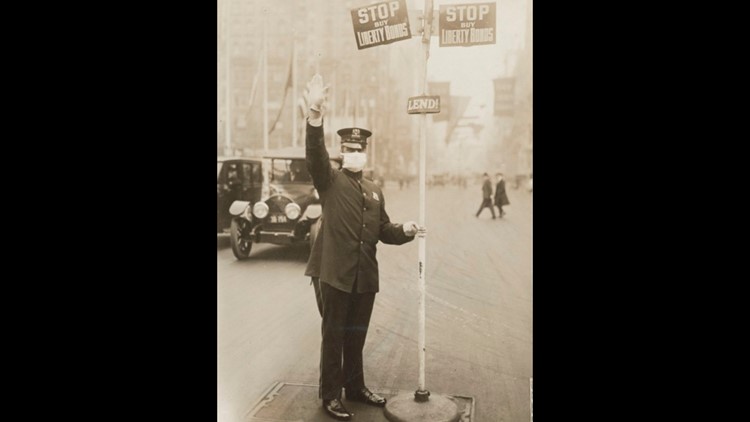

The base's chief surgeon implemented better sanitation in the barracks, required all officers and soldiers to wear masks and, a few days later, ordered soldiers to sleep outdoors in the fresh air.

Still, nearly 2,000 soldiers at Fort Gordon were treated for flu and pneumonia, and 94 of them died.

City officials told Atlantans not to worry -- with the base on lockdown, they were safe.

In late September, doctors at Camp Wheeler, the 21,000-acre Army training site outside Macon, also reported that the flu hit epidemic levels there.

Camp medical records showed that Wheeler's hospital handled about eight to 10 flu cases a day until then. But by Oct. 21, the base outbreak peaked with 118 new cases.

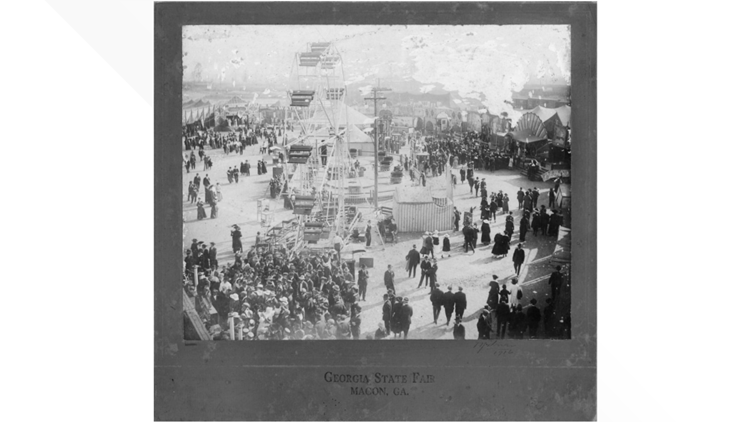

It was big news in the Macon Daily Telegraph that the global epidemic had come to the city's doorstep, but city leaders were debating another big story as well -- the fate of the Georgia State Fair.

'THE SAME OLD GRIPPE'

Macon and Bibb County's population in 1918 was just around 100,000. Fort Valley State history Fred J. van Hartesveldt wrote that much of Central Georgia was just beginning to build a public-health system.

Fort Valley and Milledgeville talked that year about building their first hospitals, and Macon planned to expand theirs.

Throughout 1918, Central Georgians had watched the flu jump the Atlantic and creep across the U.S.

But now it threatened the state's small towns and rural counties.

October was the epidemic's deadliest month: An estimated 697,000 Americans died from the Spanish Influenza, and a quarter of them died that month.

By then, Atlanta had already closed its churches, schools, libraries, theaters, movie houses and dance halls.

While people in Macon were concerned, not everybody wanted to cancel the annual highlight of the fall season, the Georgia State Fair.

The fair brought thousands of visitors to Central City Park. It was also popular with the soldiers at Camp Wheeler.

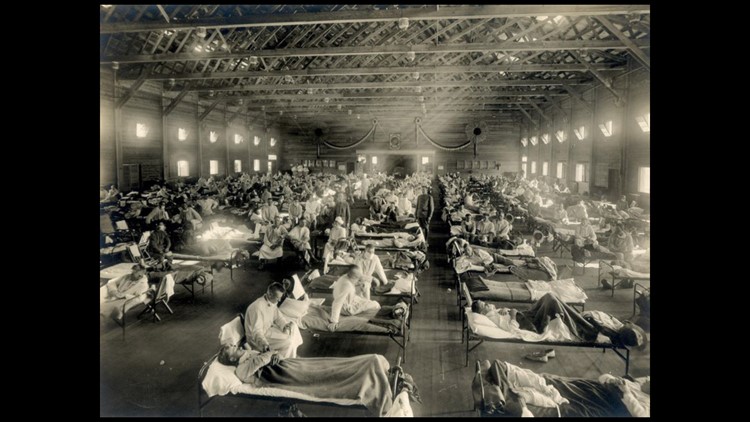

Spanish Flu in the U.S.

The Telegraph reported that every fair in America in 1918 had lost money due to the flu panic.

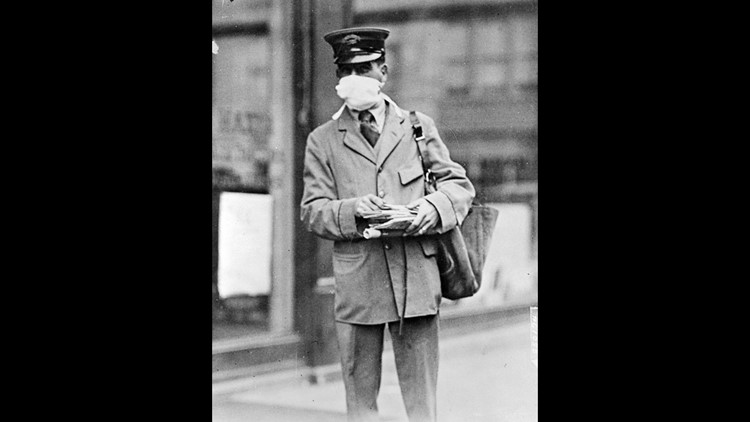

But it also reported that the city's order requiring people to wear masks "will practically eliminate all the danger."

On Oct. 22, a Telegraph headline said, "Council not afraid of the little bug."

It all came to a head at a city meeting during the last week in October.

Organizers decided to cancel the 1918 fair. Then after business people protested, they agreed to reconsider.

Van Hartesveldt described the fair debate in an essay, "Pestilence in the Mid State."

He wrote that the fair's director predicted serious losses if Macon canceled the fair. A business group offered to put up $30,000 to cover costs if the fair was postponed.

But one local doctor scoffed at the concerns. Dr. W.J. Little mocked the "scare talk" about the "same old grippe" seen every year.

Besides, fair backers said, the flu was already declining at Camp Wheeler and elsewhere.

City leaders agreed to let the fair go ahead, starting Nov. 11. In its same issue, the Telegraph reported that the Superior Court had canceled its November trials due to the flu.

And two days later, the Telegraph reported 93 new cases and eight deaths at Camp Wheeler.

"The fair opened as planned," van Hartesveldt wrote, "and there was little said to suggest that the epidemic was continuing."

Macon ended its mask requirement on Nov. 6 and school reopened on Nov. 11, the same day the fair gates opened up.

On Nov. 20, Macon had 104 new cases, but city leaders decided there was no need to shut the fair down early, re-close the schools or stop public meetings.

As the fair ended, a Telegraph editorial said, "The influenza is probably worse in Macon right now than it ever has been,"

Van Hartesveldt fumed, "It is hard to avoid the conclusion that the Macon authorities chose saving the Fair over protecting the health of the patrons."

He blamed the "personal venality" of fair organizers and business leaders.

The 1918 fair also lost money, $3,000. He called that poetic justice.

'COMMUNITY AND COMPASSION'

October was worst of it, but the Spanish flu gripped Georgia well into 1919, fading and then coming back, several times.

In the end, historians say, it struck every Georgia city and town, even remote rural areas.

Augusta was hardest hit. So many nurses became ill that a hospital put nursing students in charge of shifts and hired teachers to work as nurse, cooks and clerks.

In Athens, the University of Georgia suspended classes indefinitely.

And in Atlanta, city leaders did everything from shutting down public gatherings for two months to ordering the city's streetcars to keep their windows open, for ventilation.

But the plague still killed untold thousands -- one UGA report estimated Georgia's death toll at 30,000.

In the end, state officials admitted they were too overwhelmed to give the U.S. Public Health Service accurate final numbers.

The Atlanta Constitution estimated statewide losses at $45 million from medical costs, funerals and lost wages.

Printers, retail sales and meat packers were some of the fields hit especially hard.

But van Hartesveldt wrote that the "poorly understood horror" of the 1918 flu brought health reforms to Georgia and the midstate.

The next year, a doctors' group met in Macon to review the pandemic. They recommended that every Georgia county have a board of health, supervised by the state.

They urged the state's smaller cities to expand their health-care systems. And they said coroners should issue a death certification for every death.

"Overall, the region's institutions and people acted well," van Hartesveldt wrote. "Goverment, managed, with the help of the medical and public-health authorities, to fnd help for the ill. The schools made a real effort to protect pupils from infection. That they failed was due to ignorance that went beyond the school board."

He added, "The willingness of people to help the ill and their families, even crossing ractal lines, which was certainly beyond the custom of the day, showed true senses of community and compassion."

NOTE: Information from various online historical sites was used in compiling this story, including the National Archives, the Centers for Disease Control, Influenzaarchive.org, The New Georgia Encyclopedia, U.S, Army medical records, flutrackers. com; and Fred. J. van Hartesveldt's "Pestilence in the Mid State: The Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919 in Middle Georgia."

MORE HEADLINES

STAY ALERT | Download our FREE app now to receive breaking news and weather alerts. You can find the app on the Apple Store and Google Play.

STAY UPDATED | Click here to subscribe to our Midday Minute newsletter and receive the latest headlines and information in your inbox every day.

Have a news tip? Email news@13wmaz.com, or visit our Facebook page.