MACON, Ga. — Have you ever used platforms like "ancestry.com" or "23 & me" to trace back your family history? Have they left you wanting to know a little more?

Well, researchers in Macon have been working on a genealogy project since 2018 that will help Central Georgians dig a little further into their family tree.

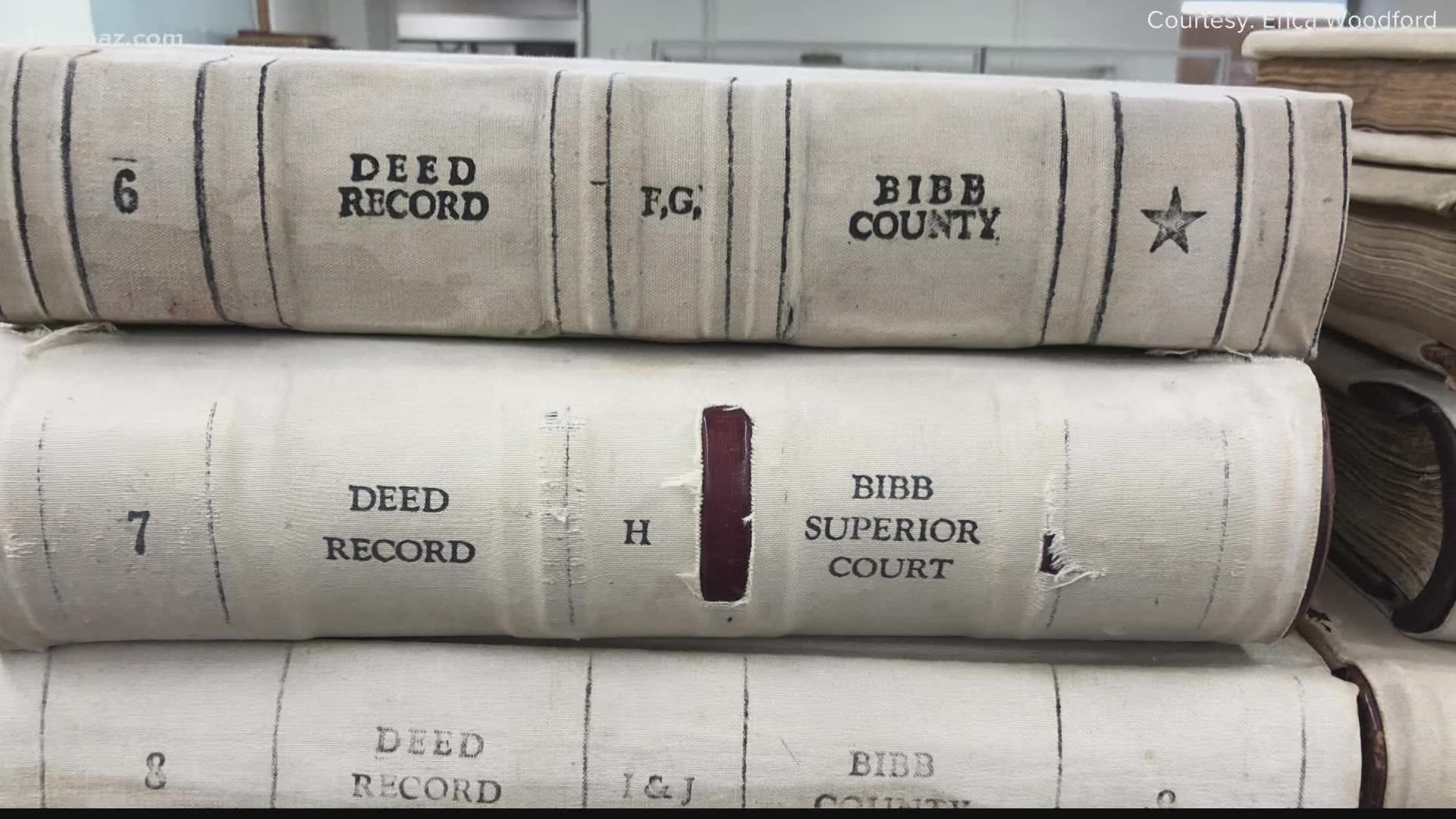

Untold Stories of enslaved African Americans have been sitting in the Bibb County Courthouse for decades.

That is, until Superior Court Clerk Erica Woodford stumbled across slave deeds in a vault of the courthouse.

She came upon a written record of an 11-year-old girl described to have fair complexion and long-straight hair. She was described as "warranted to be sound and well" and she was to be sold for $750.

"It gave me goosebumps, and made the hairs on my arm and the back of my neck stand up because it was so unreal to find these records," Woodford says.

So she gathered a team, including Chief Deputy Clerk Stephanie Miller, Mercer University's Director of Africana Studies Dr. Chester Fontenot, and students from the university to catalogue and digitize the information in the deeds.

They are now working to turn that information into a more accessible, searchable website.

With 980 slave transaction documents found in the Bibb County Courthouse, researchers say that soon, many people will be able to learn a lot more about their family's past.

"Our family is basically from Hancock County, then it migrated to Washington County, and then from Washington County to Macon," says Brenda Williams.

Williams is her family historian, studying their history since 2013.

"I wanna know who I am, and where I come from. The other piece of that that's really important is I wanna know who owned us," she says.

Williams says the research hasn't been easy, because to find history of written documents prior to the 1870s, you'd have to go to a courthouse.

"Most of the courthouses burned. Had it not been for the clerk taking the time to index those books, or getting the books indexed, we would have lost all that valuable history," she adds.

She says with these documents, she was able to access more information about her great great grandmother Linnie Haines.

"That was very challenging when I found those records to know who did that. Not that I hold them responsible, I don't hold anyone responsible for what their ancestors did, but its still good to know," she says.

She was also able to help other relatives.

"I was able to go there with my cousin when she came to visit, take her there and find out information about her great great grandfather just through those books," Williams says.

Dr. Chester Fontenot says not knowing family history is a common thread in African American culture.

"What characterizes the African American experience, no matter where we are, is disruptions as a result of slavery. Most people don't know where they come from," Fontenot says.

But this research will give them primary source documents to help them build-up their knowledge. He says the books also show how much slavery was embedded in Middle Georgia culture.

"Anytime the mayor could use city funds to purchase a slave for his use, to work in his office, and also at home, but also in his office, I think that's huge," he adds.

These books also tell us more about the enslaved people in the community.

"These enslaved people were used to build roads, and do road repair for the city. They were leased out to the railroad to build the railroad here," says Woodford.

She says they also had connections to churches, and says some were used as collateral to make purchases.

They say this research has even uncovered ties to street names.

"It was amazing to me one day when I put two and two together, when I'm driving down Napier Avenue, and I just read five deeds that conveyed humans as slaves from one Napier to the other Napier," Woodford adds.

Stephanie Miller adds that this project could change the community outlook moving forward.

"We need to understand where we've been, so maybe we will be a little less casual when we decide to name a community some type of plantation. Maybe we'll decide that's not the type of community we want to be anymore," Miller says.

No matter who you are, they say this research is for everyone.

"There are genealogical purposes that are available to anybody who is part of this community, so its really about highlighting the fact that we are a family. We are a community in more ways often then we think, and maybe its that we even share blood, says Miller.

They say this also isn't to point blame or cause shame.

"We're promoting history, and this history will prompt healing. This isn't to point fingers or to blame. Its to shed light on the rich robust history of Macon and Bibb County," says Woodford.

"I see freedom in this, I see love in this project, and I also see healing in this project," added Woodford.

Williams says her goal is to donate all her family research to the Georgia Historical Society in Savannah, to make it easier on future generations.

All research dating back to 1823 is currently available here.

However, their planned searchable website won't be available until 2023.

If you'd like to follow along with Williams's search and deep dive into her family history, you can check out her website Let the Ancestors Speak.

WHAT OTHER PEOPLE ARE READING: