'It's a matter of life and death': How a brutal family history drives a Macon woman to the polls

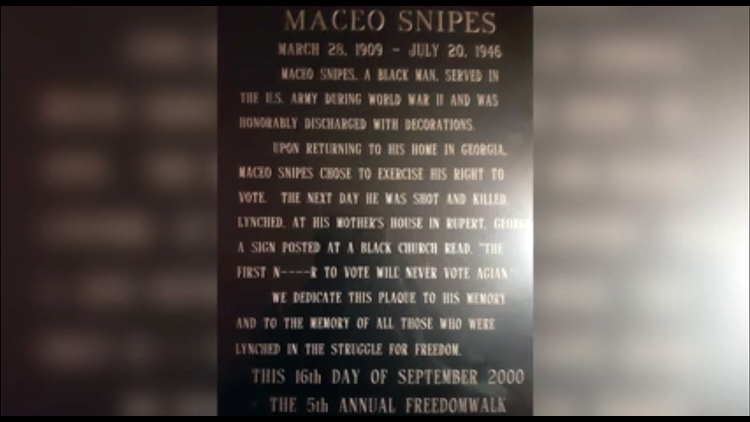

Maceo Snipes was the first Black person to vote in Taylor County. His family says his vote cost him his life.

'If any Blacks come to vote, they will be killed'

Early voting in Georgia ends on Friday before Election Day on Tuesday.

Georgia voters are shattering records as they head to the polls this year. However, the right to vote didn't include a lot of people for many decades, and for some, it was downright dangerous to even try.

Cassandra Jones-Deshazier from Macon says voting is personal to her.

"I feel like it's a matter of life and death," Jones-Deshazier said.

Her step-grandfather, Maceo Snipes, was a World War II veteran. According to historians, he was also the first Black person to vote in Taylor County during the Georgia gubernatorial election in 1946.

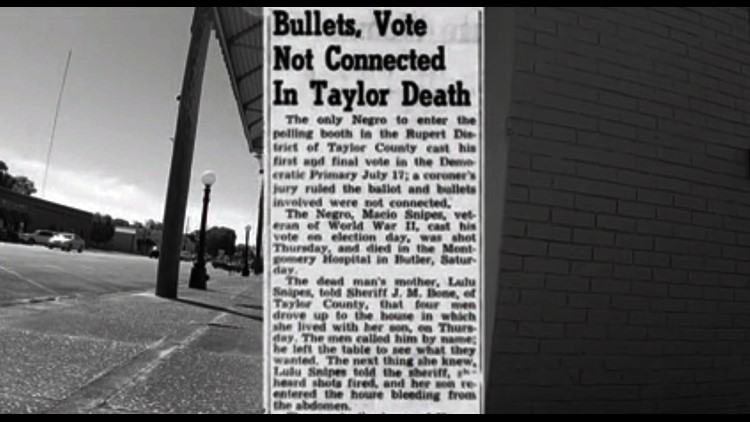

"He went and voted, and he was gunned down," Jones-Deshazier said.

She says her grandmother told her a leader in town warned that if "any Blacks come to vote, they will be killed."

She says shortly after Snipes voted, several men showed up to his home, asked him to come outside, and shot him.

Brutal family history drives Macon woman to the polls

"My recollection from what my grandmother told me was that the hospital was so far, and he walked," Jones-Deshazier said. "When he got to he hospital, he had lost so much blood, and they didn't have any 'Colored' blood to give him, so he bled to death and died."

The threats didn't stop there. Jones-Deshazier said her family was then threatened that they'd meet the same fate if they attended Snipes' funeral. She says her step-grandfather was buried in secret, and to this day, his burial site is unknown.

She says the fear and violence her family endured now drives her to vote.

"My step-granddaddy lost his life, but there are so many other people who lost their lives and died and paved the way for us to be able to do this," Jones-Deshazier said.

'The best weapon we have is making a plan to vote'

One person who doesn't take the responsibility of voting lightly is former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams. After she narrowly lost the governor's seat, she dedicated her career to voting rights and created her voting organization, Fair Fight Action.

"Voter suppression may take different forms, but it's been around since the beginning of this country, and it has three pieces: can you register and stay on the rolls, can you cast your ballot, and does your ballot get counted?" Abrams said. "What preceded the Voting Rights Act is a very violent approach to imposing those three impediments to the right to vote. What we have found in the 20th century is those same attacks on our right to vote look like administrative rules, they look like bureaucratic barriers, they look like user error, but we need to understand is, often, it's not you, it's them. It is the system."

She says there's one way to overcome the barriers.

"If we want voting to be easier this cycle, if we want Election Day to be the right process, and we want election season to go smoothly, the best weapon we have is making a plan to vote," Abrams said.

It's advice Jones-Deshazier heeds as she prepares to cast her ballot. She urges everyone to exercise their right and make the choice to vote.

Snipes' killer never faced any charges, but his death did spur a then-sophomore at Morehouse College to write a letter about basic rights to the Atlanta Constitution newspaper. The student was Martin Luther King, Jr.

What is voter suppression?: A closer look

Voter suppression is actually part of the US legal code, Title 18 Section 594, to be exact.

By definition, voter suppression is any effort, either legal or illegal, by way of laws, administrative rules, or tactics that prevents eligible voters from registering to vote or voting.

In practice, it's enforcing voter ID laws, closing polling places in certain neighborhoods, reducing hours or purging registrations.

Those tactics disproportionately impact the communities of color and the elderly.

The Voting Rights Act of 1965 tried to eliminate them, but in 2013, Supreme Court case Shelby County v Holder rolled back a lot of those protections, especially in southern states.

In a 5 to 4 decision, Chief Justice John Roberts wrote that the law was based on "decades-old data and eradicated practices," and that there was "no longer such a disparity" for communities of color.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg famously dissented that's like "throwing away your umbrella in a rainstorm because you are not getting wet."

Since that Supreme Court decision, 25 states -- many in the south-- have put in place new voter restrictions, like ID requirements and cutbacks in early voting.

More on Maceo Snipes, 'A man whose death inspired the teenager who led the movement'

An excerpt of an article from The Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project at Emory University:

Maceo Snipes must have felt a great sense of pride after he cast his first vote in the contentious 1946 Democratic primary for governor. Like many black World War II veterans, Snipes returned home, to Butler – a town in western Georgia with 1,972 residents – with an honorable discharge and a determination to exercise his rights as a citizen.

For months, Snipes had considered the risks associated with his exercise of the franchise. Even by Jim Crow standards for racially charged elections, this was a particularly fragile time for a black man to seek to vote. The most provocative campaign issue was specifically whether any African-Americans should be allowed to vote in the Democratic primary. Georgia had long allowed only whites to vote in the Democratic primaries; advocates of the whites-only primary said blacks could vote instead in the general election. But since Georgia was essentially a one-party state where winning the primary assured victory in a pro forma general election, the black vote had no influence.

In a decision the Georgia political establishment vowed to defy, federal courts earlier in 1946 had struck down the whites-only primary. So Snipes was seeking to vote in the first election held without the statewide ban on black voting. That campaign pitted one of the most racially polarizing figures in Georgia history, two-term former Gov. Eugene Talmadge, who pledged to reinstate the all-white primary, against a somewhat more progressive James V. Carmichael.

Despite threats from the Ku Klux Klan in the run-up to the July 17 primary, Maceo Snipes took the bold step to become the first African American to cast a vote in Taylor County. What happened over the next several days in Butler and two hours away in Monroe, Georgia, would grab headlines across the nation, especially in the African-American press, and prompt a young Morehouse College student, Martin Luther King Jr., to write a letter of response to the editor of The Atlanta Constitution.

The day after Snipes voted, four white men arrived in a pick-up truck outside of his grandfather’s farmhouse, where Snipes and his mother Lula were having dinner. The men, rumored to be members of the local Klan chapter, called for Snipes, who came outside to meet them. During their encounter outside the house, Edward Williamson, who sometimes went by the name of Edward Cooper, shot Snipes in the back. Williamson, like Snipes, was a World War II veteran.

As recounted by his descendants, Snipes was wounded and struggling but still ambulatory as he and his mother walked about three miles to the home of Homer Chapman for help. Chapman owned the land where Snipes and his mother worked as sharecroppers. By one account published at the time, Chapman “helped take the wounded Negro to the hospital.” Snipes’ descendants today say Snipes and his mother went to the home of Snipes’ sister Katie, whose two sons, Sam and Eddie D., drove their uncle to Montgomery Hospital in Butler. Snipes waited in a hospital room that better resembled a closet, as the doctor on duty attended to other patients.

Approximately six hours lapsed from the time Williamson shot Snipes until the doctor performed surgery to remove the bullets, the family would later say. The story that still resonates from that day in the Snipes family carries the same theme of medical neglect found in other Georgia civil rights cold cases: Not long before he died, Snipes was talking actively with his family. The white doctor at one point said Snipes would need a transfusion, then said it would be impossible because there was no “black blood” available at the hospital. Mirroring every other facet of life in the Jim Crow South, the enforced separation between blacks and whites extended to blood transfusions. Without a transfusion, Snipes died from his injuries two days later, on July 20.

More historical information:

A 2015 commemorative look at one of the most important pieces of legislation of the civil rights movement: the Voting Rights Act of 1965, from the Library of Congress.