Killed on camera: Macon woman's death caught on Facebook Live

Facebook took the video down, but not before a copy was uploaded to another site. There, it racked up more than 200,000 views.

'What we lost, we can never get it back'

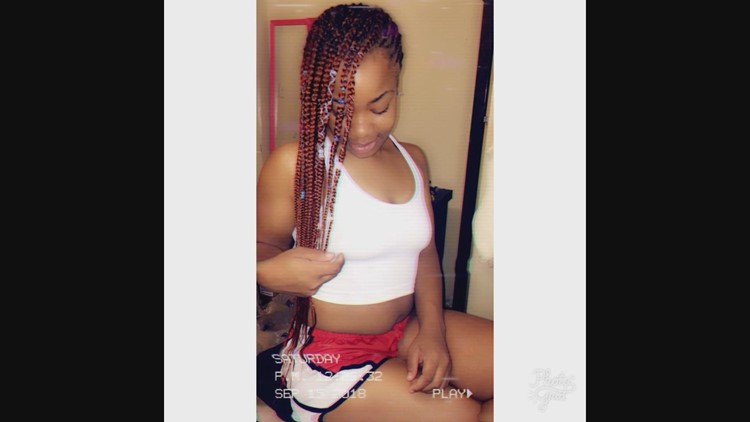

39 people had already been killed in Macon last year when Tynesha Hammonds stepped into the car.

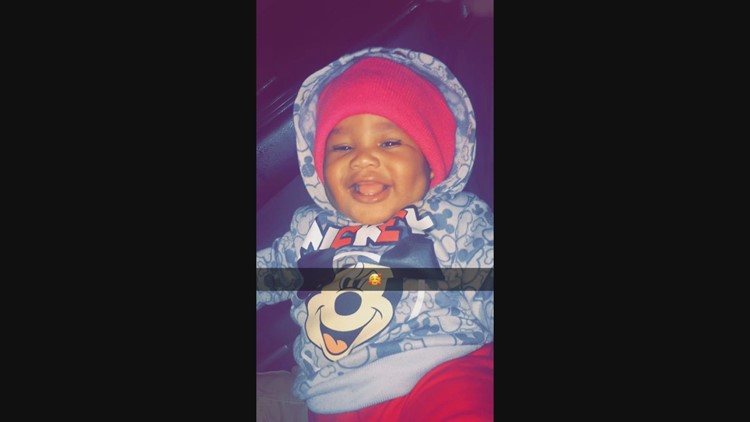

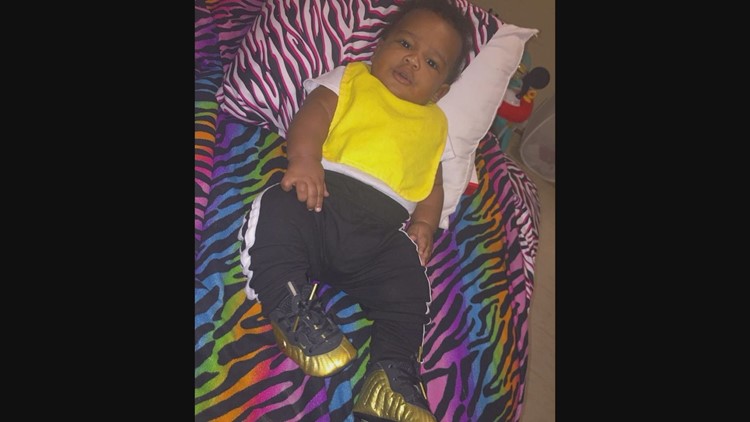

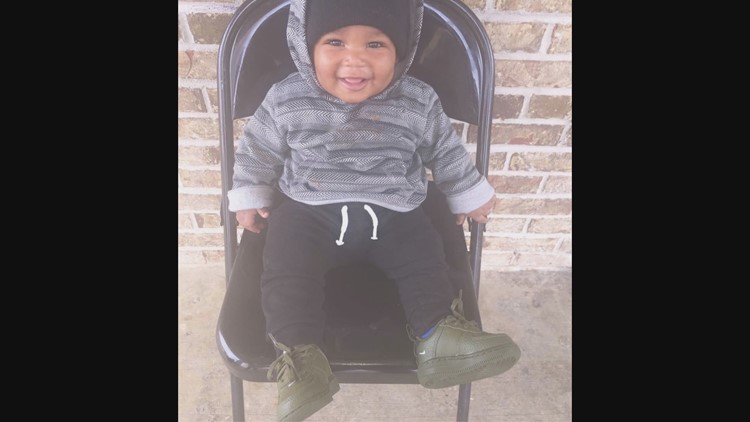

It was just days before Christmas. Tynesha left her baby boy Amari behind as she headed out to enjoy a night with friends.

Hammonds began streaming her night on Facebook Live. Her friends were watching in real time, when something went dangerously wrong.

Just 20 years old, Hammonds was dead. She'd been shot to death less than a block from her mother's house. Her Facebook Live video captured it all.

The crime shook up her Bloomfield neighborhood.

"I keep my kids in the house," said Joey Stephens at the time. "It's sad, you know what I'm saying? Because they be wanting to come out and play but it's just too dangerous right now."

And it rocked Tynesha's family. "My fiancé had to tell me actually, 'When they mention a white sheet, it's -- I don't think she's here anymore,'" said Sara McMiller. "I just, I couldn't, I couldn't wrap my mind. Not her, not Tynesha."

McMiller, who is soon to be Tynesha's cousin-in-law and who says she's known Tynesha since she was a baby, says Facebook soon took the video off their site. However, somebody apparently made a copy of it first.

That copy was quickly uploaded to flyheight.com, a site full of provocative user-uploaded videos.

Despite the family's wishes, for months the video of Tynesha's last living moments remained on the site, racking up more than 200,000 views.

McMiller says she emailed the site, asking them to take it down. "Once it's on the internet, it's out there, but I'm like, as much damage control as y'all can do, please, please take it down," she said. "Amari's not going to be a baby forever. Her son is gonna have a social media one day. I would hate for him to come across that video."

PHOTOS: Tynesha Hammonds and family

Sara McMiller understands getting a video removed from the internet can be a complicated legal situation, but she says the moral question has an easy answer.

"If you have a heart, take it down," she said. "Think of her child -- if you won't take it down for anybody else, think of her mother and her child. Her mother had to bury her daughter."

In the end, it appears Flyheight agreed. We reached out to the website asking about the video. We didn't get a written response, but days later, the video was removed.

Months in the making, Tynesha Hammonds' family finally got the result they were looking for, but what rights would you have if you found yourself in a similar situation?

Tynesha's is an awful, extreme case, but almost all of us now have images of one kind or another we don't want made public.

"The facts about internet usage, people's behavior on the internet, all of the things it makes possible both for good and for bad are changing so rapidly, the law hasn't really had time to catch up," said Adam Holland, a legal scholar at Harvard's Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society.

He says by recording an image, you automatically get a copyright for it.

"By the mere act of making that video, you have a copyright in it," said Holland. "You don't need to fill out a form, you don't need to do any registration. The moment that the content becomes fixed in a tangible medium, that's a quote from the law, you have a copyright."

According to the scholar, that can work to your advantage.

"You could absolutely go to a website...and say I have copyright in this particular video, there is a copy of that video located...on your site...I'm the copyright owner and I want it taken down," he said.

In technical terms, it's known as a DMCA takedown notice. DMCA stands for the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Passed in 1998, Holland says it gives legal muscle to online content removal requests.

"The vast majority of websites will comply with a DMCA notice," he said. "A DMCA notice is the official way with which you ask for something to be removed based on your copyright in it."

According to Holland, "it's extremely easy...you basically just have to send whoever is linking to or hosting the material a short letter that checks five or six boxes, you know, you say 'I'm the holder of the copyright or I represent someone who does, here's where (the video) is located, I believe that it's infringing, date, etc., and that's it."

Specifically, the law states a notice must include the following:

--A physical or electronic signature of either the copyright holder or someone who is acting for them

--Identification of the copyrighted work you think is being infringed. In other words, proof that the content you're talking about really is content you created.

--Identification of where you believe the infringement is taking place. In other words, where your work is being posted without your consent and infringing on your copyright.

--Your contact information (address, phone number, email, etc.).

--A statement in "good faith" saying, essentially, that you believe you did not authorize the content to be posted by the allegedly infringing party.

--A statement under penalty of perjury that the information in your takedown notice is accurate and that you have the right to act on behalf of the copyright holder.

Most major sites provide online forms that streamline this process, like Facebook and Google. If they don't, you'll have to look up the site's copyright agent, typically locatable in the site's legal information tab, and send your takedown notice to him or her.

Doing all this, he says, does not require an attorney.

Holland says going to court is another option, if the DMCA notice isn't effective. There, you likely would need an attorney and would typically be asking a judge to rule that the content defamed you in some way. This can be costly.

Holland says the takedown notices are usually the most effective tool, but he cautions that the law is not "one-size-fits-all," and those takedown notices, he says, work better in some situations than in others.

And on sites where third party users upload content, which is common now, Holland says things can get even trickier.

"(A website) can, if they want, say, 'Well, we will pass this along to the user and let them know you've made a claim and then, you know, basically, you can take it up with them,' or they can honor it," said Holland.

But overall, he says they're usually a copyright holder's best line of defense, (other than, he says, never creating content that might cause problems for you in the first place).

As for Tynesha's family, this struggle appears to be over, but their search for justice is far from it. Her case is still open. The killer is still on the loose.

What they want now is answers.

"All we want is closure," said McMiler. "We may never move on. There will never be another Tynesha, but allow her mother to get to sleep at night. Give her that peace of mind, because what we lost, we can never get it back."

If you know anything about her case, you can call Macon Regional Crimestoppers at 1-877-68CRIME.