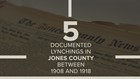

JONES COUNTY, Ga. — Through the end of the 19th century and most of the 20th century, Georgia carried a dark past.

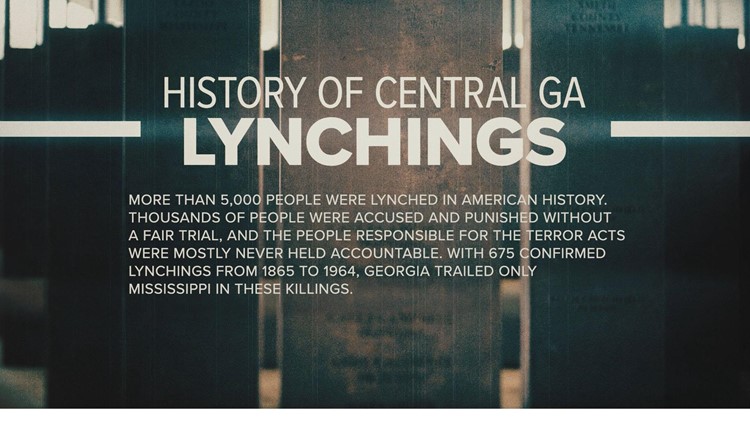

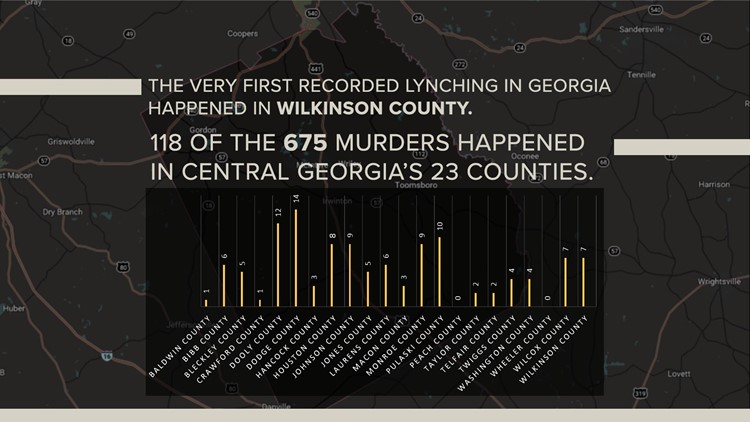

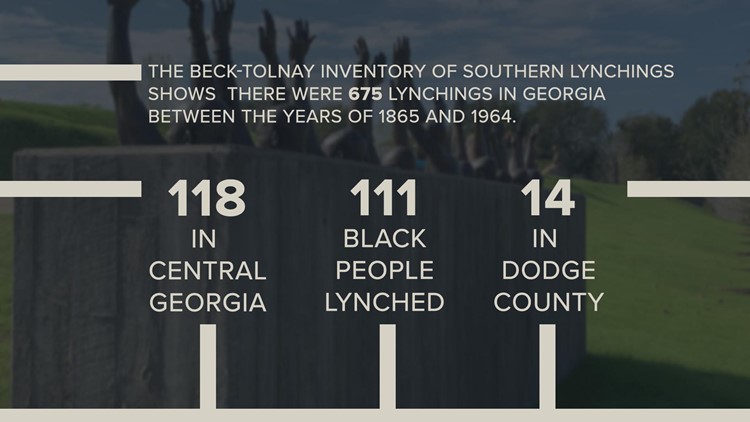

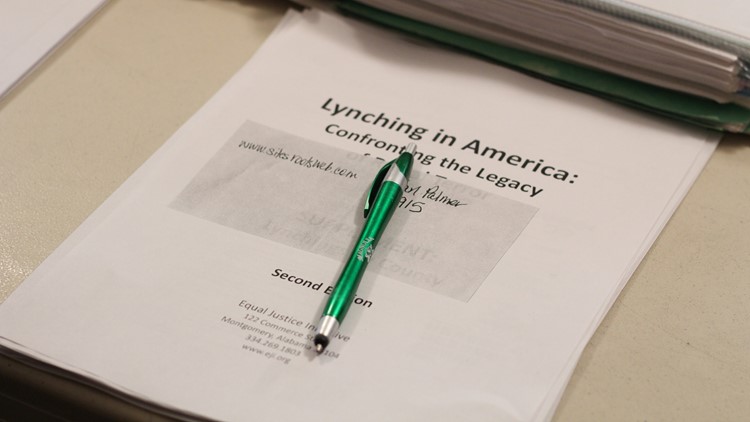

It’s documented that around 675 people lost their lives to lynchings in Georgia during that time.

The majority of the people killed were African-American and nearly 120 of the 675 victims were from Central Georgia.

Those victims were often falsely accused of crimes, and their killers were seldom held responsible for the murders they committed.

A Jones County family knows that hopelessness all too well.

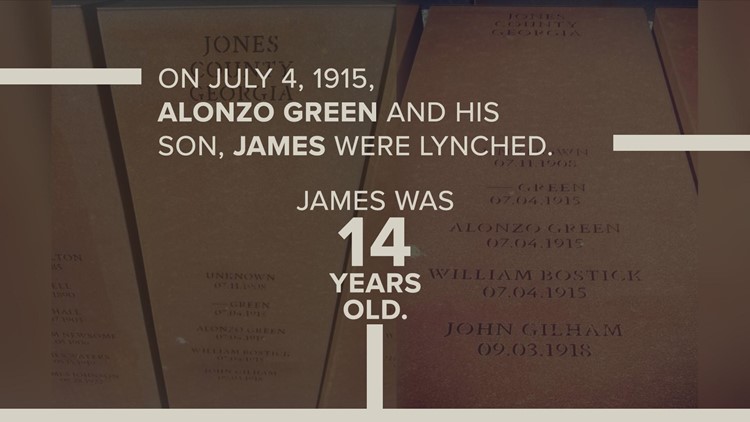

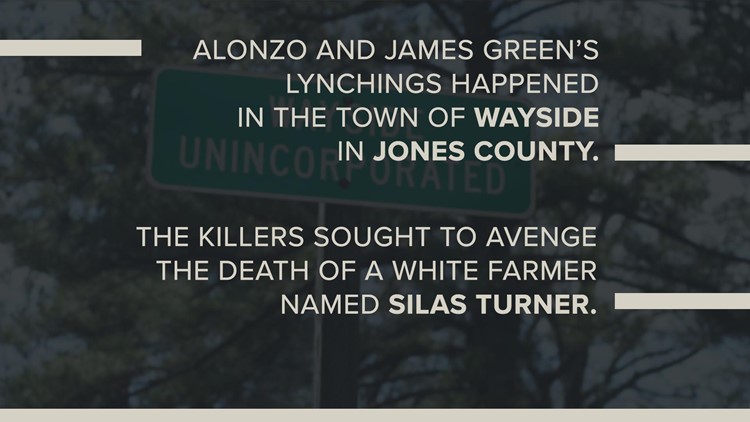

On July 4, 1915 in the town of Wayside in Jones County, Alonzo Green and his 14-year-old son, James, were on their way home when they were attacked by a lynch mob of hundreds of people.

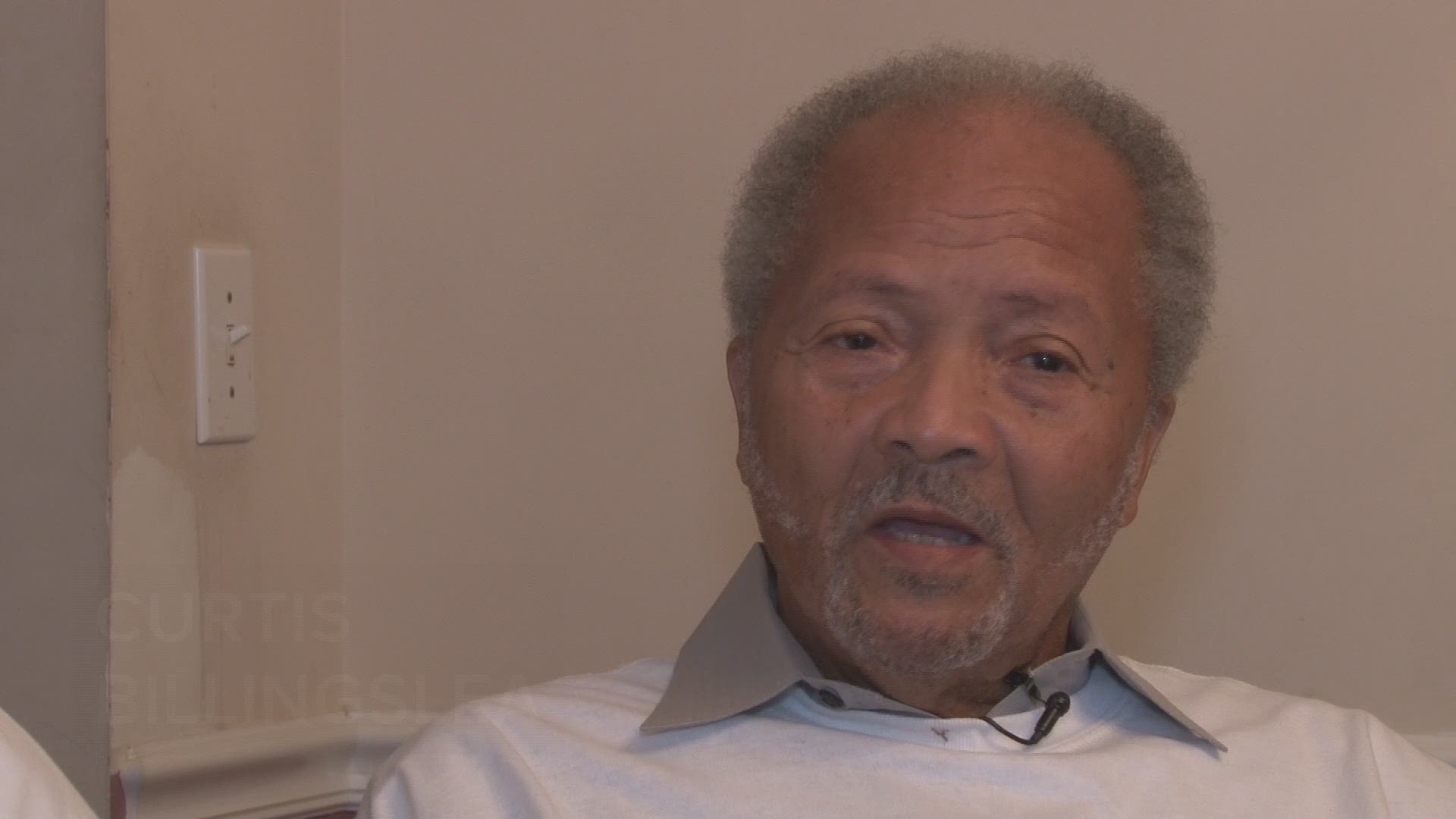

"[My mother-in-law] had an uncle that was riding home in a mule and wagon, and he was shot," said Curtis Billingslea, who heard the story from his mother-in-law. “He had a teenage son with him at the time, and he exclaimed to the crowd, 'I’m going home to tell my mother.' After his dad was shot, then he was shot.”

What happened to the two was rarely talked about in the community, but the oral history was passed down through the Green family.

Billingslea’s mother-in-law’s father was Alonzo’s older brother.

The family says at the time of the murder, Alonzo’s wife was eight-months pregnant with their daughter.

"It was just a 'picnic' to bring justice upon someone," Billingslea said. "It didn’t matter who."

The term "picnic" in the Jim Crow era often referred to feelings that lynch mobs would pick a "nig," or black person, to hang or punish for crimes they were accused of committing.

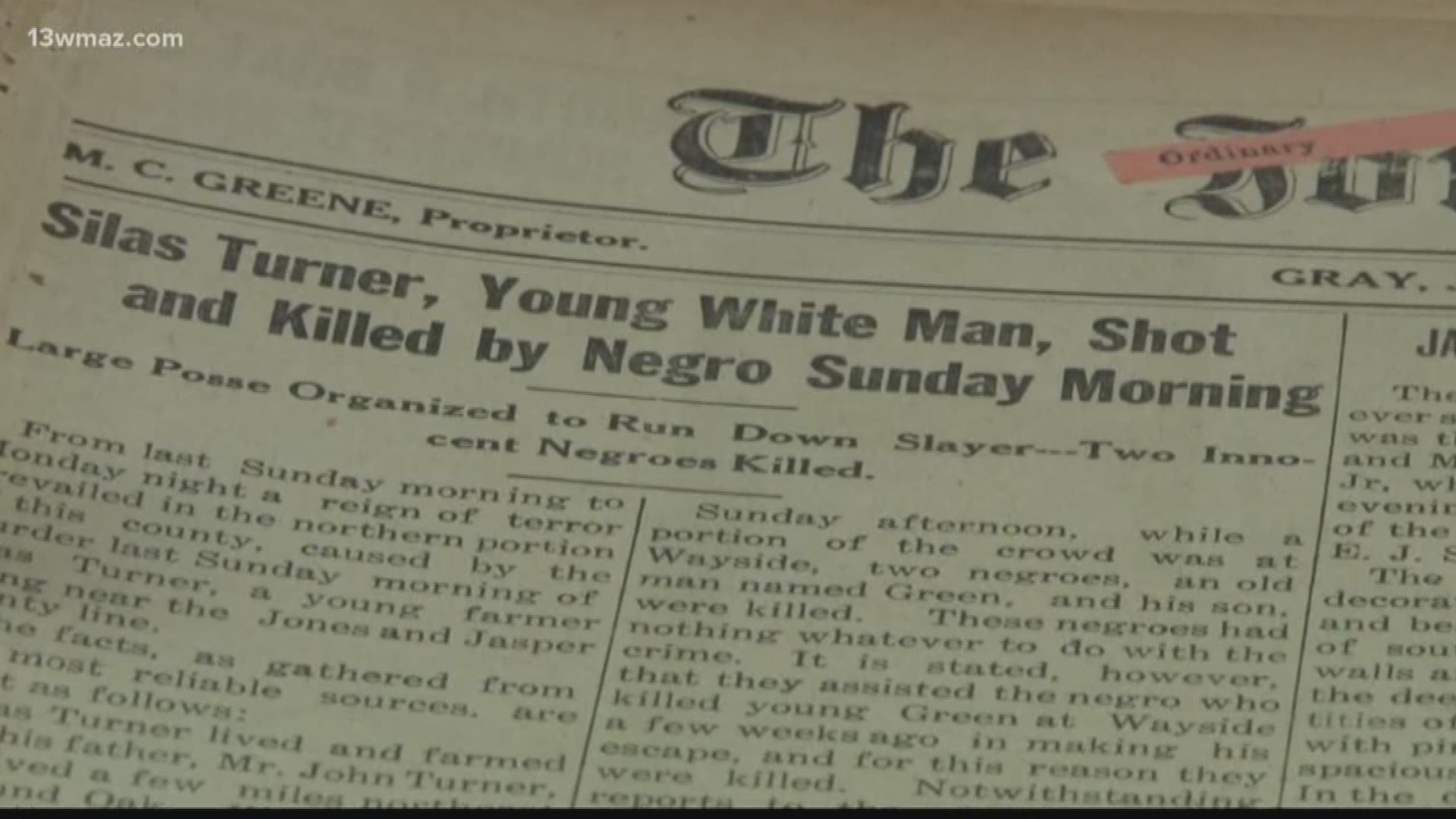

The Jones County courthouse temporarily houses the archived county newspapers.

In one article dated July 8, 1915, it states a mob was trying to avenge the death of a white farmer named Silas Turner.

The article says the mob ended up lynching three people over two days. However, in reference to the Greens, it says, "these negroes had nothing whatever to do with the crime."

DATA: History of Central Ga. lynchings

The family says it's sad and a shame that their lives were taken unjustly and senselessly.

"Totally unfair, due process is due everyone, but there was no due process there," Billingslea said.

During those years, there are some reports a white man named Woodall Green spent time in jail for killing the black Greens, but it's believed he was never charged.

After researching family history, Billingslea believes Woodall and Alonzo could've been related, since Alonzo’s grandfather was white.

"Justice was never served," Billingslea said. "Even if the person they caught was the guilty person, the lynch mob rule does not apply to justice."

But a new community group is working to achieve a delayed justice -- or at least recognition -- for the Green family.

"I thought that this was a piece of history that should come to light in Jones County," said Billingslea’s cousin, Janice Kitchens.

Kitchens spearheaded the group’s formation with the purpose of creating a memorial for lynching victims in Jones County.

Kitchens says she was inspired after visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama.

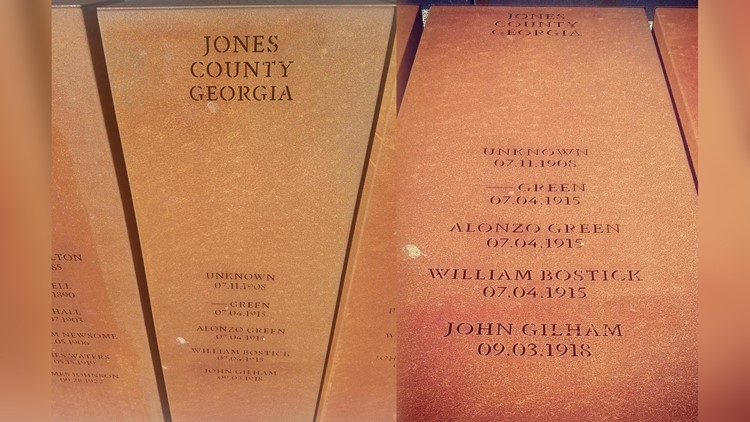

The museum honors more than 4,000 documented lynching victims in the country. They have pillars transcribed with the names of each victim in every county where a lynching occurred.

PHOTOS: Jones Co. group tries to find lynching site

Kitchens says a spokesperson from the museum told her they were making duplicates of the pillars available this year to counties that want them.

Kitchens says there is a process to bring the memorial home to Jones County.

The group will have to create a proposal, which they’re working on finishing, then make a historical marker and finally return to the site of the lynching to do a soil collection.

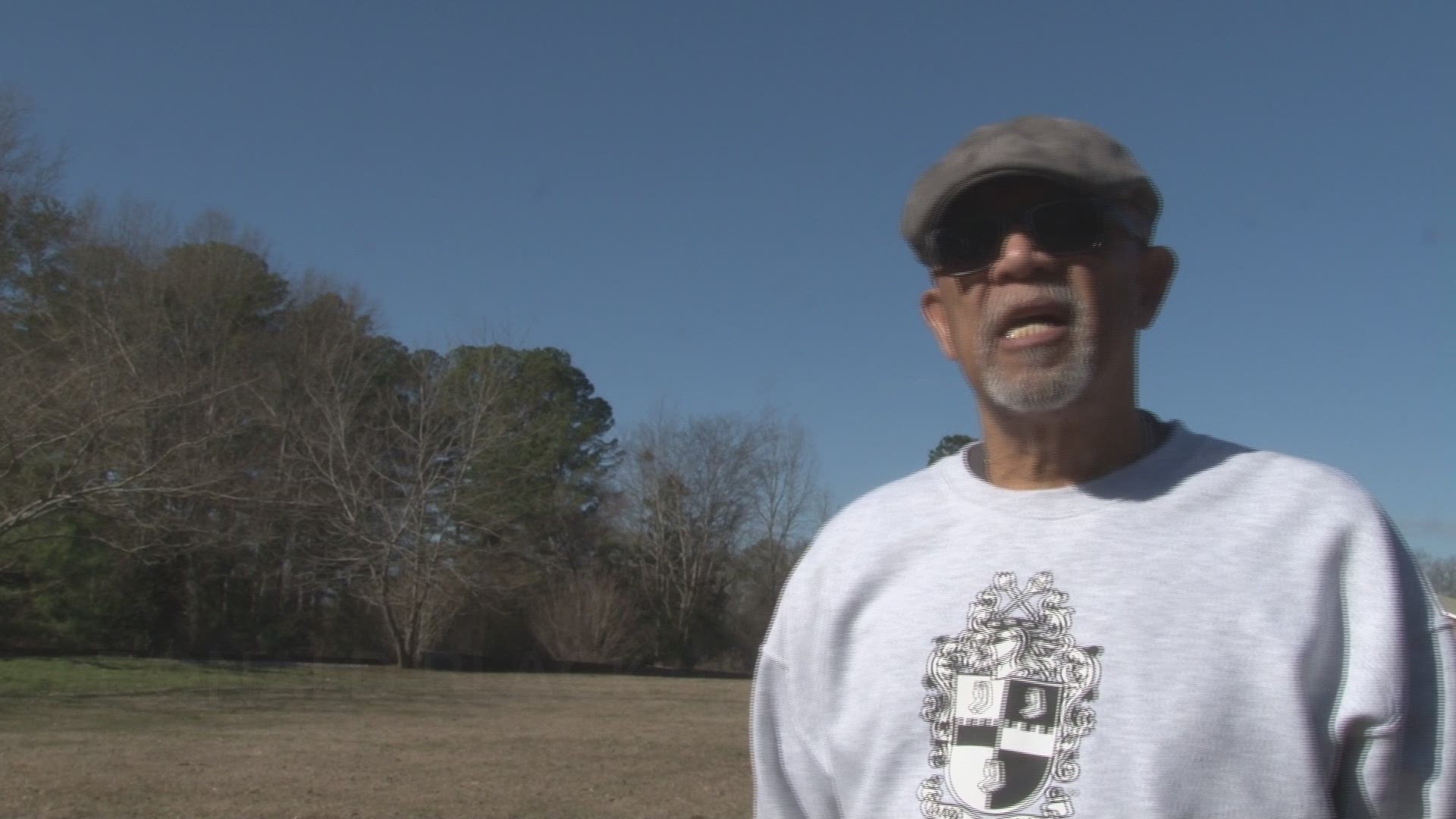

The group has spent time researching possible locations since it's not known exactly where the lynching happened. They believe the property of an old pimento factory would be the only place large enough to accommodate a crowd of hundreds in the early 1900s.

"If we can collect the soil from this place, it would assuage the spirits of Alonzo and his son James… that his ancestors that are here, we’re trying to make sure that we let their history be told," said Donald Black, a community leader who’s helping to bring the memorial to the county.

The group says they’re not looking to blame anyone. They just want to remember what happened in order to move forward.

"Digging up the past of those folks who were left out of the history books," Black said.

The group says they’d like to have the pillar back in Jones County by July, around the anniversary of the lynching. They’re hoping to work with county leaders to make it possible and are scouting potential final resting places for the marker, including the Jones County courthouse.