'I was forced out of farming': Central Georgia's black farmers still face struggles today

Black farmers in the south, including Central Georgia, have faced decades of discrimination trying to make a living off the land.

One of the largest industries in Georgia is farming.

Often, it’s a way of life passed down from generation to generation. However, for some black farmers, that way of life has sometimes been a fight filled challenges, discrimination, and land loss.

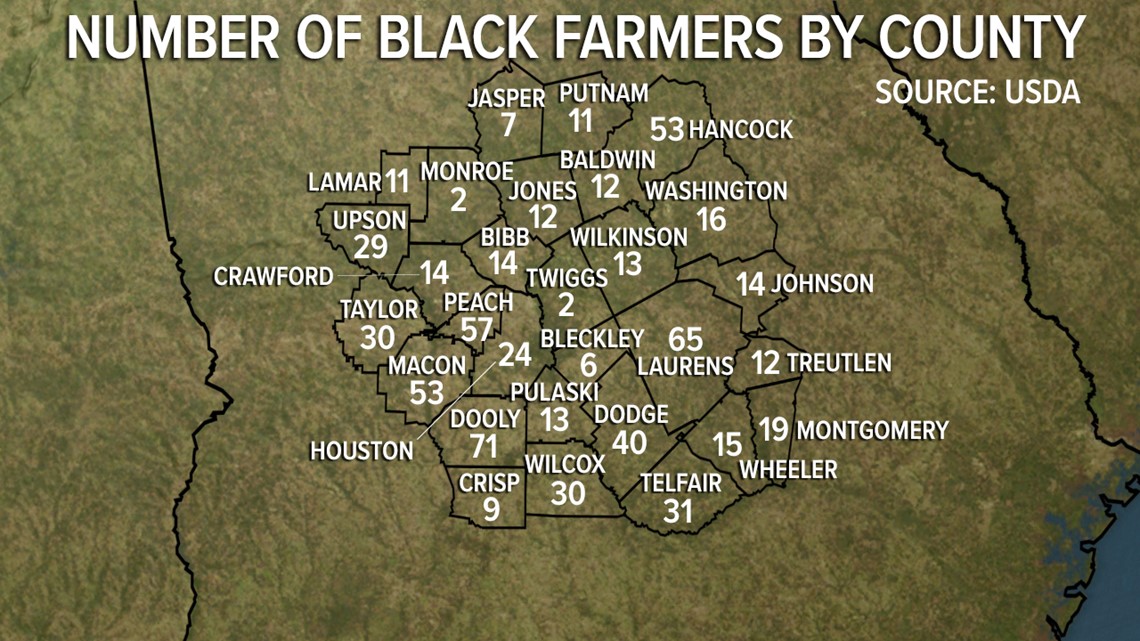

Black farmers by the numbers How many are in Central Georgia?

Across the country, there are 3.4 million farmers. According to the United States Department of Agriculture’s 2017 Census of Agriculture, there are 48,697 black farmers in the country, and 2,870 of those farmers are in Georgia.

Georgia has the fifth highest number of black farmers in the country, and many of them live in Central Georgia.

One of those farmers is Earl Rawls. He currently owns and farms on land in Pulaski and Houston Counties, but his family has owned land in Pulaski for generations.

“My grandmother and grandpa, everyone in my family still owns land,” Rawls said.

His cousin, Herbert Battle, also farms on passed down family land in Hawkinsville.

“When I come in the world, that place was there,” Battle said.

The two cousins say they remember growing up on the farm and helping their dads and uncles with the plows and mules used to tend the land.

A look back at farming from the beginning "It's in our DNA to love the land"

It’s work some say is entrenched in the black soul.

“It’s in our DNA to love the land and work with nature, so farming provides you the opportunity to feed that urge,” said Veronica Womack, executive director of the Rural Studies Institute at Georgia College and State University and Black Belt scholar.

Womack says the appreciation for farming goes back to Africans' earliest days in America.

“When enslaved Africans were working the field, many of them also had their own garden,” she said.

But she says slavery was just the start of challenging times.

“Rural communities are struggling, and black farmers who live in rural communities are also part of that struggle. Land retention is also challenging, heir property,” Womack said.

Successful generations that own land like Rawls and Battle’s family is unfortunately uncommon.

“At the height of African American land ownership, we owned about 15 million acres, and presently we own less than 3 (million),” Womack said.

She says that statistic is part of a raw Southern history.

“Many lynchings were connected to economic situations, and land was a part of that,” Womack said. “Many African-Americans simply had to leave the rural south, some in the dead of night, because someone wanted their property.”

The residual effect of slavery and Jim Crow presented itself in the following decades in the form of USDA loan and farm aid discrimination. That eventually led hundreds of black farmers to come together and file a class action lawsuit against the USDA in 1997.

That lawsuit was named Pigford v. Glickman. It claimed the USDA had racially discriminated against African-American farmers between 1981 and 1997. The USDA admitted their wrongdoing, resulting in a $1 billion settlement which is reported to be the largest civil rights settlement in history.

The settlement was supposed to give $50,000 and loan forgiveness to farmers who proved they were discriminated against and had filed a complaint against USDA before 1997. However, nearly a third of farmers' claims were denied, and many Georgia farmers say they still haven’t seen the benefits of the lawsuit.

“It did not solve the issues for African-American farmers,” Womack said.

The effects today Decades later, black farmers say they still struggle to get the financial aid they need.

Battle says he still struggles with getting the money he needs to run his business.

“A lot of the stuff I stopped planting, because I couldn't get the loan to work it with,” he said.

The Cooperative Extension Program at Fort Valley State University holds meetings to help farmers succeed. Many farmers who attend those meetings alongside Battle have similar complaints.

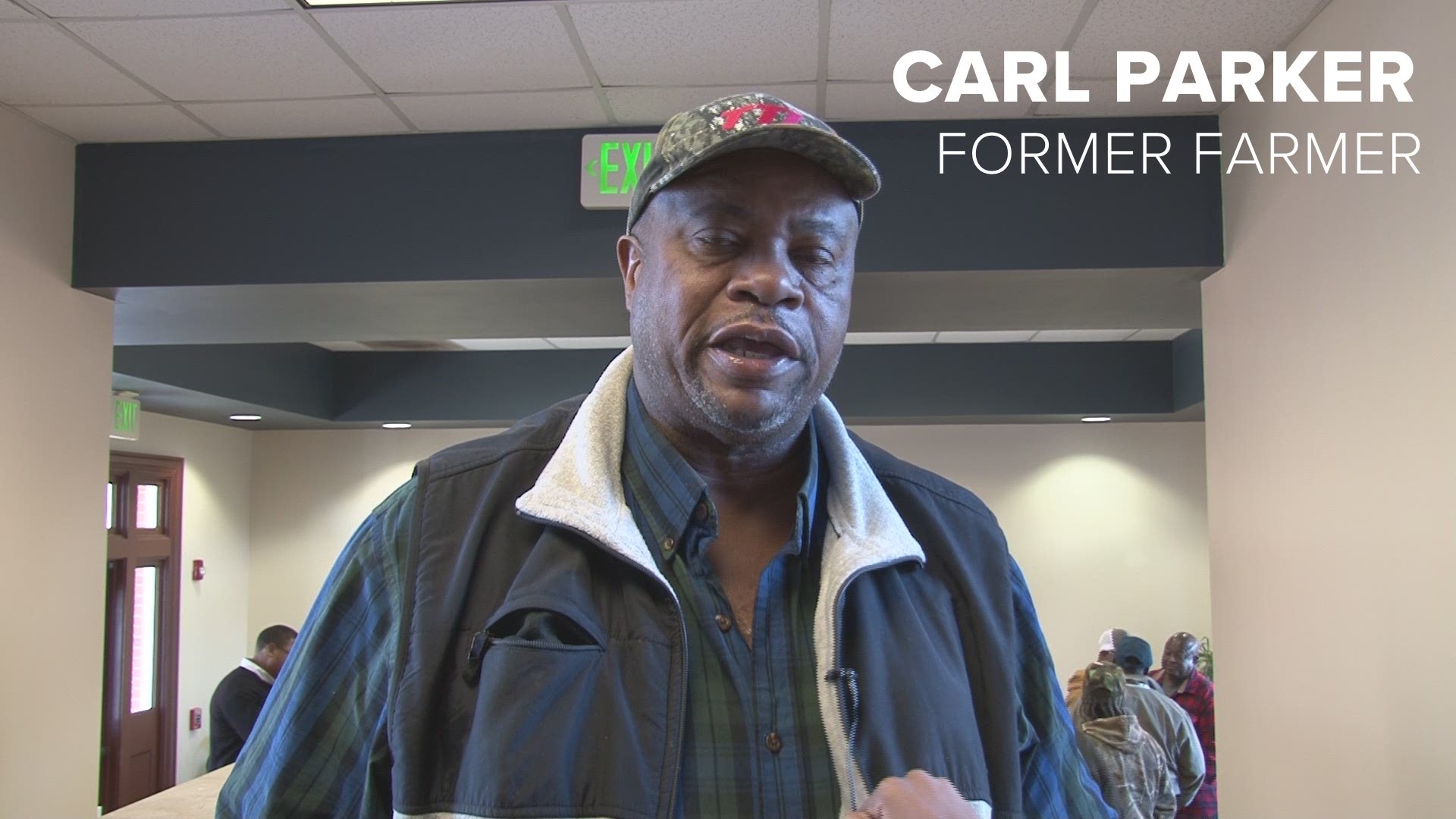

“I was forced out of farming, because I couldn’t get the money to fund my farm,” said Carl Parker, a farmer from Worth County. “I went in several times to try to get loans, and they told me if you've ever been delinquent with USDA, that you'll never be qualified for another loan.”

Womack says that’s been a common problem through her research.

“You find yourself in a situation where you can't get credit,” Womack said. “You have prior debt that you can't pay, and then you can't produce.”

She says that threatens more land loss.

“Folks worked really hard to get the land, and once it's gone, the likelihood of you being able to get that amount of acres in the future is very slim,” Womack said. “When you lose your family property of 150 acres, in some places that could be a million dollars worth of property that’s gone, depending on the land quality. Where do you find another million dollars?”

It’s a fact Rawls and Battle take seriously.

“Owning real estate, they don't grow any more of that,” Rawls said.

It’s why he and his family worked so hard to keep the land growing down the family line.

“One generation to the other one, they kept it fixed like that,” Battle said.

He says his family often gets inquiries from people trying to buy their land.

“They tell them it's not for sale,” Battle said.

They say a price tag can’t be put on generational wealth.

“I'm trying to generate mine, so my children and grand kids can have something to go with,” Rawls said.

His hope is that his land stays in his family for generations to come.

PHOTOS | Earl Rawls on his farm

STAY ALERT | Download our FREE app now to receive breaking news and weather alerts. You can find the app on the Apple Store and Google Play.

STAY UPDATED | Click here to subscribe to our Midday Minute newsletter and receive the latest headlines and information in your inbox every day.

Have a news tip? Email news@13wmaz.com, or visit our Facebook page.