WARNER ROBINS, Ga. — In 2024, Georgia public schools will screen kindergarten and first through third grade students for dyslexia. Before that happens, the state intends to train teachers on how to teach the students properly.

"A myth that gets repeated by a lot of people is that kids that have dyslexia aren’t intelligent, but in fact, the one in five that have dyslexia, most of them are above average IQ," mother and dyslexia advocate Hilary Laxson said.

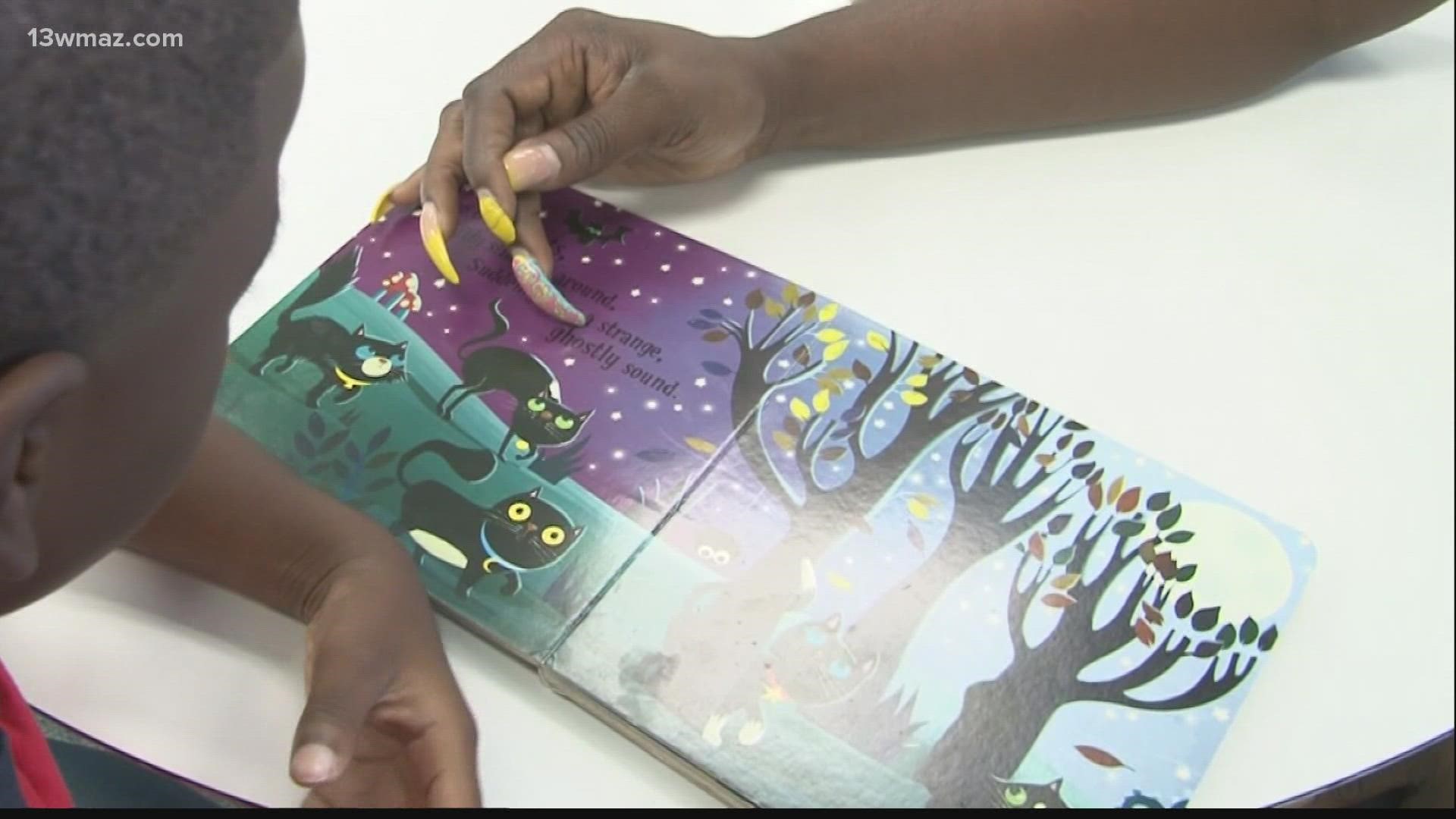

Dyslexia is a learning disorder that makes reading difficult.

Hilary Laxson says her daughter has the disorder along with ADHD and an auditory processing and language disorder. While in Houston County schools, she didn’t feel the county was equipped to meet her needs.

"It seemed like none of the teachers had any kind of training with dyslexia, they didn’t even know how to accommodate dyslexia, and forget it if I thought they were going to teach reading intervention to someone in middle school. They just had no training to even begin trying to help her," Laxson said.

Now, the state is investing $1.5 million to cover the costs of training teachers to help students with dyslexia.

"Our teachers receive informal training regularly from literacy coaches or intervention specialists that come into the classroom that address specific needs or concerns all the way to very formal instruction," Jenny Millward, Houston County Board of Education's Director of Student Services, explained.

She says they have many teachers currently trained to help.

“We are equipped to implement strategies and interventions that address students individual needs for reading," she continued.

She says parents who believe their child may be struggling with learning can ask for what’s called an individual education plan, or IEP.

"An individual education plan with specific goals and accommodations and services that students need to access the curriculum," Millward said.

"It’s a step in the right direction because before, there were no financial incentives to a teacher to take one of these classes, there’s no professional incentive for these teachers to expand their knowledge to work with the one in five that have dyslexia,” Laxson said.

Laxson has since started a support group to help parents who have dyslexic children.

Experts say some signs of dyslexia could be confusing or skipping small words when reading aloud, having trouble quickly recognizing common words, Difficulty learning (and remembering) the names of letters in the alphabet, and seeming unable to recognize letters in his/her own name.

Resources: https://thepromiseact.org/