MACON, Ga. — In the early 1900s, downtown Macon reflected segregation and widespread business opportunities for all. In the 1920s, evidence of success for black and white businesses could be seen across the city.

Some historians say Macon had its own “Black Wall Street,” with two banks and dozens of black-owned companies doing well. Historians say downtown Macon was very busy, and everyone who wanted to work had a job.

Even more interesting was that in that era of segregation, black and white-owned businesses worked side by side. There were white and black businesses across the street from each other in Macon. This was not a common occurrence for many different communities.

Many black own businesses prospered. The evidence of this was seen along Popular Street, Mulberry Street, Broadway and especially Cotton Avenue.

People with firsthand knowledge of Macon’s black business success shared their stories, and much of it can be found in the many historical resources available.

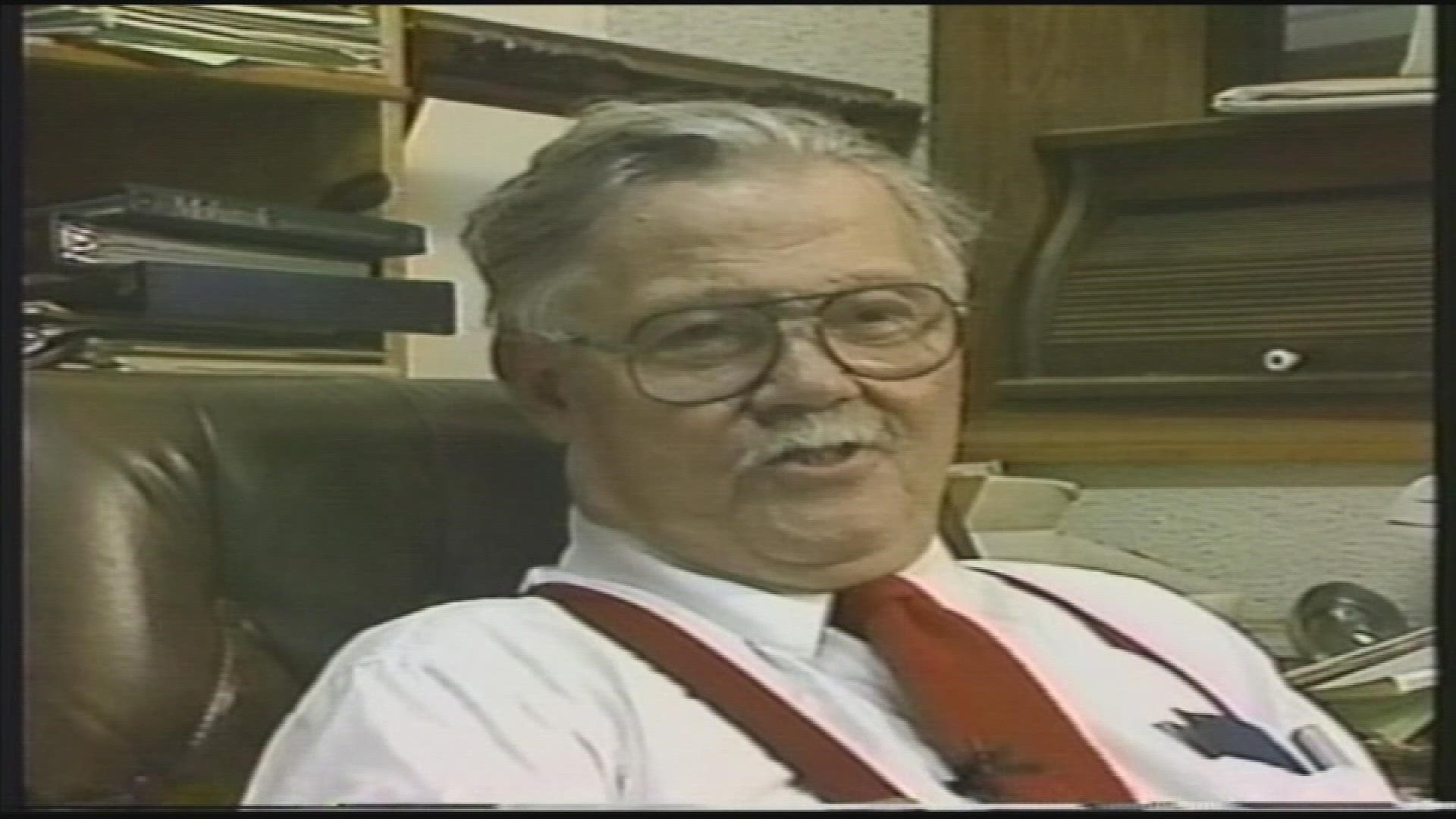

One of those documentaries, produced in 1993, was called Black Cultural History in Macon, Georgia. It included many interviews with individuals and family membered, many of who are no longer with us.

Macon Historian Dr. Thomas Duval has the historical records of the many businesses on Cotton Avenue and is the product of that prosperous time for African Americans. His father is the late William Duval. In the 1993 interview, he was the retired owner of Paul Duval and Sons Upholstering.

At the time of the interview, William Duval was of the third generation of a more than a 100-year-old company that was still in the upholstery business. The late Duval’s grandfather started working at a furniture factory in Macon and later started Paul Duval and Sons Upholstering.

Packing and shipping was big business in the early 1900a, and the railroad running through Macon was essential to the city’s economy. William Duval said his family’s business successfully made awnings and had a year-round upholstering business.

He said he started working there when he was 12 -year-old. Duval said Macon was surprisingly different in that black and white companies “were right together, intermingled.”

In that interview, William Duval said, “Macon was a different situation than it was for most surrounding towns that you see during that time. In most towns back then, the businesses (black) were crossing the tracks. You got to go to a certain side of town. But Macon has always been where businesses were everywhere all over town.” He said, “If you take Poplar Street down there, we had a lot of black businesses… like a black-owned real estate company, and Henry Williams had a big café.”

Duval said Macon had two black-owned banks, “A man named Douglass was on Broadway, and then a man named Hendricks has a bank on Cotton Avenue.” In the 1920s, Charles Henry Douglass made Broadway the ideal place to be.

He said when people got off work, they would pack Broadway. “Charles Henry Douglass had a bank, a hotel, a pool room, a shoe shop, a barber shop and a hotel annex. He employed a lot of people. In addition, he only has about five houses across the community that require a lot of care.” Benny Scott says he went to the Douglass Theatre often. Scott says the shows would include regular acts that traveled from New York.

“Even if you were a porter or maid, finding work around Macon was not hard for African Americans back then,” said Benny Scott. “There were plenty of jobs available because most of the businesses downtown there were booming, when they moved the blacks out, then the businesses died.”

Benny Scott said his brother Leonard Scott, owned the tall building right across the street from the Macon City Hall. He also owned the building at the corner alley up from the Elks Lodge. “And he ran a cafe, called Gene’s Cafe and a package store for several years.”

Scott says at least four black tailors were doing well around Macon. Black own businesses lined Popular Street, including leather shops where they made saddles and related items. Scott recalls a man named W.T. Barnes, who worked in one of the leather shops for over 60 years. There were also at least two to three blacksmith shops.

He, too, remembers Henry Williams, who had a restaurant about a half block from the Macon City Hall on Popular Street. Black and white people ate in that business. They had a petition that separated the blacks from the whites who ate at the front of the restaurant. Scott said most people who ate there came from other counties around Macon. “People like farmers and folks who came to Macon to shop during the weekdays and weekends,” said Scott.

African American draymen stayed busy in downtown Macon because white and black businesses constantly moved supplies. Scott says they moved materials, wooden crates, and supplies.

The historical term for “drayman” was the driver of a dray, or low, flat-bed wagon without sides, generally pulled by horses or mules. This was a common way to transport all kinds of goods.

There were black draymen and who had horses, fine horses, and wagons, who would park at the corner of Popular and Third streets. Later when they became mechanized with moving vehicles, they would part at other areas around the city, quickly finding work.