Broken furniture, broken hopes: Georgia mom stuck in loop trying to get help for son with autism

As part of an 11Alive investigative series, we examine the gaps in the system created to help children with mental and developmental disabilities.

In the past five years, 1,268 children in Georgia were abandoned or surrendered to the state due to a parent's inability to cope or the child's behavioral issues. More than half of those children were abandoned more than once, generally in relation to a mental or developmental disability.

A series by 11Alive's investigative team, The Reveal, looked into the numbers, but more importantly, spoke to families who said their only option was to give up custody of their children.

"Abandon" sounds like a harsh term for a heartbreaking situation. The solutions are just as complicated as the reasons why parents make the decision. But the law is crystal clear.

One Georgia mom candidly shared her journey and explains why her son Jaylen hasn't been able to get the help he needs.

#KEEPINGJAYLEN

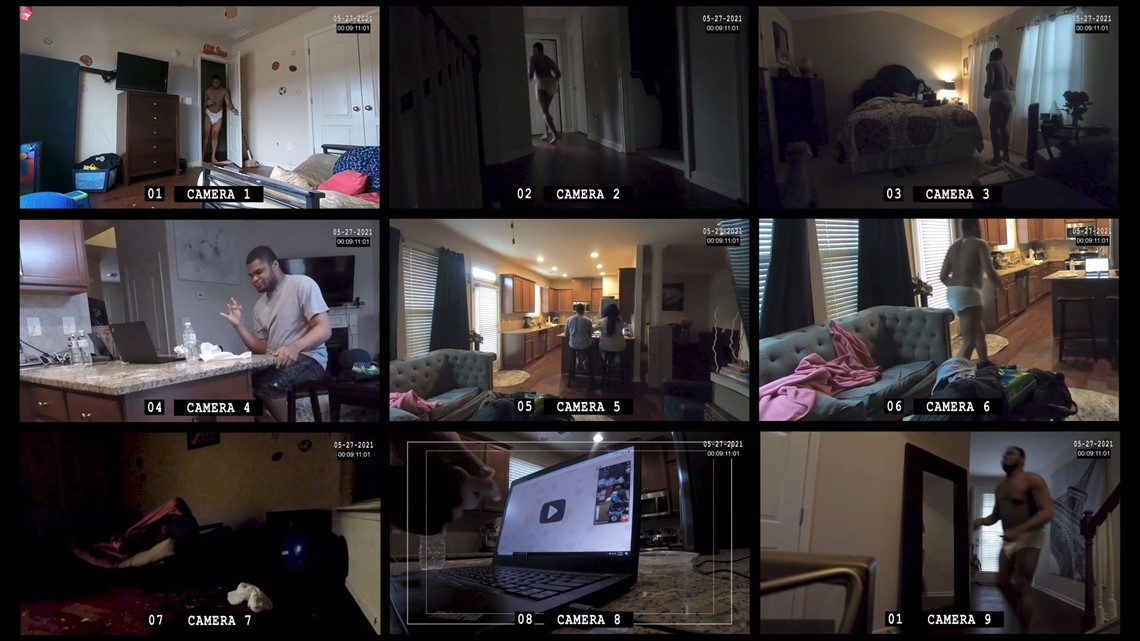

The Reveal set out to capture a typical day in Jaylen’s life, a non-verbal teen with autism. We set up cameras throughout the townhome he shares with his mom in Lawrenceville, entering only to change out batteries and memory cards.

The video clips captured a mother and son eating breakfast, talking about their day. It was the height of COVID-19, so Jaylen attended school remotely, since he wouldn’t keep on a face mask. And then there were hours of repetitive roaming as soon as his mom shifted her focus to work.

Jaylen’s actions are often abrupt. He can be loud. He’s 17 and strong, so when he rocks a stair banister, it breaks. When he repeatedly jumps on his bed, the metal frame bends. But Maria doesn’t know how to stop him or what he’s trying to communicate when he does these things.

His sleep is also restless, which means even in the middle of the night he is moving around the house.

“He gets up at like one or two o’clock in the morning,” Maria Manning explained. “Sometimes he screams. Sometimes he tries to open my door to get my attention.”

PLEADING FOR HELP

She remembers a few years back when he started to intentionally, physically injure himself. Even then, there was no way as a single working mom, she could watch him 24 hours a day. She pleaded with the state for help.

“I said if you guys don’t help him, I’m at the part where he’s just going to get dropped off at Children’s. And I meant it. Did I want to do it? No,” Manning said, fighting back the tears. “I felt it was the only way I could get some help for him.”

“Dropped off” – means abandon – to force the state to pay attention to their needs. She was talking with Georgia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities (DBHDD). They may administer some of the programs she was seeking, but it’s actually up to the Department of Community Health to approve the services and make sure they’re available. Either way, she said neither agency answered her plea.

“Sometimes I lock the door when he’s having a meltdown. He’s out there crying, I’m in my room crying. Help me. How do I help him," Manning questioned.

Susan Goico, the Director of the Disability Integration Project at Atlanta Legal Aid, said this is about the time she starts talking about EPSDT, a federal mandate for children receiving Medicaid.

“That stands for Early Periodic Screening, Diagnostic and Treatment,” she explained.

It’s a lot of words – but children like Jaylen really need others to understand them, because at its core EPSDT means children covered by Medicaid should get any service deemed medically necessary.

SERVICES NEEDED

The challenge is that doctors don’t always know how to express the supportive services that help keep the child healthy. It’s clear what medications or treatments might aid a physical disability, but behavioral therapies and in-home aides to help with bathing and quality of life are often not considered in an assessment of medical need. That’s where Goico often has to step in.

“If a physician says this child needs behavioral supports in the home because it’s impossible for the parent to stay up 24/7 just to keep their child safe and healthy, then I would say that’s not a convenience. It’s medically necessary,” Goico explained.

Once that need is identified she says, “the state not only has to provide these services or have these services available, but they have to help the families access them. It’s not enough to say, give a mom or dad, here’s a list of providers with some phone numbers. Call 50 and see what you get. That’s not going to work,” Goico said.

Yet Manning says that’s exactly what she’s experienced. If that’s the case, Goico says Georgia is breaking the law. The reality, there are no consequences when states fail to meet the needs – outside of a lawsuit by a family fighting for services.

FLAWS IN THE SYSTEM

It’s not that Georgia doesn’t care, 22-percent of our state funding goes toward healthcare, according to the Budget and Policy Institute. But families said we either need to spend more – or spend differently.

“What we see all the time is children with more complicated diagnosis, or multiple diagnosis, fall in what I call the Grand Canyon of service gaps. Because the service systems have a hard time working together,” Goico said.

The state knows needs are not being met. It is a state agency, the Division of Family and Children Services, that wrote a 9-page memo outlining some of the problems. In the past two years, child advocates, attorneys, and behavioral health providers have also written letters to DCH listing specific steps that could help. One group called the current system “incoherent.”

“Change is hard for people. I think human instinct has us, when someone suggests a new bold idea to have us go, 'ah, is that possible? Can that really work? Is it going to be too expensive?'” said Erica Fener Sitkoff, the Executive Director of Voices for Georgia’s Children.

“We advance laws, policies, and actions that improve the lives of children, particularly the ones that face the greatest barrier," Sitkoff said.

Right now the group is studying denials - why families with high need children on Medicaid are being told no. Their research has already revealed one problem.

“How complicated this is. As much as we have definitions for what’s medically necessary, there is a human component to this. There are people deciding that,” Sitkoff explained.

She said that means who gets what – isn’t consistent. Managed care organizations that hold Medicare contracts can simply say the requested service isn’t “medically necessary” without offering details on why.

A suggestion might be to require CMOs and private health insurance companies to list other lower level services that are available, and approved, in the family’s community. Too often, families claim they are denied access even as health insurance providers know other services are not available.

Those denials whether by Medicaid or private insurance companies can leave state taxpayers on the hook. In two years, DFCS said it spent more than $72 million on residential treatment, intensive in-home and out-of-state care because it felt the services ‘were’ needed. Not all of these children were abandoned to the system, but they do all represent the same group – dually diagnosed children with severe mental health and developmental disabilities.

And in the case of Medicaid denials, taxpayers actually have to foot the bill twice. Once to cover the child’s Medicaid plan, and the second time to actually pay for the required service.

“The sad part about this is, if I died tomorrow, he’s going to get help because I’m dead,” Manning proclaimed with a sad, yet frustrated look upon her face.

JAYLEN'S REALITY

Parents like Maria said the research needs to go further to determine why families approved for a service, don't access it. She offers a perfect example.

Jaylen is approved for behavioral therapy, or ABA, to help him find better ways to communicate. But when Jaylen was younger, Maria couldn’t juggle the limited appointment times with the hours of her job. Now that she’s working from home, therapists said at 17 – he’s too old.

“That really broke my heart because…” she said pausing to catch her breath and she teetered between tears and rage.

She knows behavioral therapy could teach her son important life skills and maybe open new opportunities for interaction within the community. “But there was always a barrier.”

While there are likely therapists that would work with Jaylen, Maria hasn’t found them. In the meantime, simple habits like rocking and jumping have destroyed several beds, she hasn’t bothered to fix the stair rail, and the couch we saw on our visit is gone.

“Right now we don’t have a couch. Like literally, we do not have a couch right now. The couch that was there, it’s gone,” Manning explained.

Gone, not from one jump, but a repetition of little jumps each day, every day. A pattern of walking in and out of rooms, turning on and off the lights. Disrupted sleep and desperate attempts to be understood. Without resources to break the cycle, Jaylen and his mom will live in a loop.

“I love my son. I love him so much but it’s like am I the best thing for him? Some days I don’t feel that way. What is he learning from me? How am I helping him? What can I do? I feel helpless. I’m his advocate and I feel helpless.”

NOTE: The #Keeping series is being told as part of the USC Annenberg Center for Health Journalism's 2020 Data Fellowship.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.