ATLANTA — Officer Larry LoBianco is a certified hero. Barely a year out of the police academy in 2016, he rescued a kidnapping victim by shooting one of the kidnappers in the leg. Then Officer LoBianco saved the kidnapper from bleeding to death by using his police radio cord as a tourniquet.

Now he’s fighting to save his career in law enforcement.

An outside psychologist hired by the City of Atlanta has ruled LoBianco unfit for duty.

“It’s just horrible,” LoBianco said. “How do you do this to a decorated officer who really has no bad history? We’re just going to cut him off,” he said, describing his treatment by the city.

The Atlanta Police Department first took Officer LoBianco’s badge and gun last December. Without his knowledge while he was on vacation for Thanksgiving, LoBianco’s lieutenant began building a file on him.

Lt. Robert E. Petersen wrote to his captain on November 30, “[Internal Affairs] concluded that due to a lack of documentation on our part, there was not enough for them to relieve Officer LoBianco from duty.”

RELATED: ‘In my opinion, he saved that guy’s life’: Officer plugs bleeding artery of kidnapping suspect

The lieutenant started creating documentation, writing a memo that would ultimately strip Officer LoBianco of his police powers, and land him in the office of a psychologist who has ended the APD careers of two other officers.

In all three cases, the psychologist wrote that, because of the officers’ “overt efforts at impression management, the evaluator was unable to obtain an accurate diagnosis.”

The city kept sending officers to this same psychologist, even though she was not able to diagnose them. That psychologist ruled all three suffered from, “maladaptive personality functioning” that rendered them “unable to function effectively in a law enforcement capacity.”

Atlanta’s municipal ordinances were changed in 2017 to prevent officers from appealing the opinions of psychologists who determine them unfit for duty. No second opinions are allowed.

Officer Received High Marks

LoBianco had built an impressive series of annual reviews with above-average scores and arrest stats, including a compliment directly from Police Chief Erika Shields a month before he was relieved of duty.

After the 2016 police chase and shooting where LoBianco rescued the kidnapping victim and saved the life of the kidnapper he shot, a sergeant recommended LoBianco and his partner for a commendation, praising their “quick response, bravery, and professionalism.” He had fired just three shots in two engagements, and then took extraordinary action to stanch the arterial bleeding of a suspect who is now serving a life sentence in prison.

A sergeant described LoBianco’s “outstanding work ethic, productivity, investigative techniques…but where Officer LoBianco really excels is in his investigations. He puts in more effort in solving complex cases than those with similar experience.”

LoBianco was promoted to the elite APEX anti-gang unit, where he continued to rack up top arrest numbers, but where he sometimes clashed with coworkers and supervisors, resulting in multiple transfers.

One supervisor wrote in his evaluation, he’s “a handful, but…a loyal and hard worker.”

A civilian who witnessed Officer LoBianco single-handedly subdue an angry suspect wrote to police commanders, complimenting the officer’s “composure and ability to contain the situation,” the witness wrote, “it was rush hour at a busy intersection, people were honking continuously, a crowd of people were gathering to watch, and the suspect would not relent. In my view, all of these factors created a tense situation that could have escalated, but the officer maintained control of the situation.”

Chief Shields wrote back to her command staff, “that’s some really nice feedback and says a lot about the officer.”

LoBianco’s captain forwarded the message to him, adding, “very proud of you.”

Just four weeks later, Officer LoBianco was characterized as out of control, and a threat to himself and others.

The Burglary Case

The turning point, based on police records obtained through the Georgia Open Records Act, appears to be a burglary investigation that infuriated LoBianco’s supervisors shortly before LoBianco left for vacation.

Burglary calls typically involve an officer taking a report and some witness statements, then turning over any investigation to detectives. But LoBianco actually tried to solve the case, which was close to the end of his watch that day.

Records show both a sergeant and a lieutenant questioned LoBianco’s efforts to track the burglary suspects, after one of the victims gave a detailed description in his 911 call. They wanted him to come back because the next shift needed his police cruiser, LoBianco said.

LoBianco wrote in his incident report, “as I was getting ready to leave, [the victim] informed me that he saw one of them; the one in the red hoody and skinny jeans.” Officer LoBianco then wrote, “I was able to see what apartment he went into,” and he knocked on the door to talk with the men inside.

After filing the incident report, LoBianco was questioned by different supervisors who said that he did too much or too little.

LoBianco wrote to his supervisors on November 13 of last year, “I am very disappointed with some of the officers in this zone as well as some of the sergeants…it seems like when ever you try to do the right thing you get shot down.”

► WATCH | The Reveal Sundays at 6 p.m. for the nations only local weekly investigative show

While he was on vacation, supervisors referred LoBianco to APD’s Office of Professional Standards to open an internal affairs investigation alleging the officer lied in the burglary incident report.

A detective investigating the burglary wrote, “I asked [the victim] if he pointed out a suspect to the officer while the officer was on scene. He said no, he never saw the suspects’ faces.”

LoBianco told internal affairs investigators the same story in a sworn statement, but the burglary victim could not be located when detectives tried to get a written statement contradicting Officer LoBianco.

Eventually, investigators would determine that the allegation of filing a false police report could not be sustained. They suggested only a written reprimand because LoBianco forgot to activate his body camera when searching the victim’s apartment.

Police commanders and city officials continued to use the allegations that LoBianco had been untruthful as a pretext for referring him for a psych evaluation, even after the Office of Professional Standards had been unable to sustain the allegations.

OTHER NEWS: Police officer tells citizen ‘suck my ****!'

Early Warning Memo

The beginning of the end of Officer LoBianco’s career with the Atlanta Police Department was an ‘early warning’ memo written by Lt. Robert E. Petersen to the director of the city’s Psychological Services unit on December 5.

The memo was written just five days after the lieutenant wrote to his captain that there wasn’t enough documentation for the Office of Professional Standards to relieve Officer LoBianco of duty.

Lt. Petersen’s memos alleged that Officer LoBianco had a “hit list” and was suspected of “sexual harassment” of the male sergeant directly above him in the chain of command, however each of those allegations was paired with information refuting them, sometimes in the same sentence.

The lieutenant wrote, quoting unidentified sources, “I was told by others who have worked with Officer LoBianco that if he likes someone, they’re on his ‘good list,’ but if he feels like someone had crossed and/or betrayed him, and/or he doesn’t like someone, they are on his ‘bad list.’ It is alleged that he has a list of people on some sort of ‘hit’ or ‘bad’ list, but I have not seen any evidence to support such a claim.”

Lt. Petersen also included a list of ten specific instances the lieutenant wrote added up to sexual harassment. Records show that list was sent to the lieutenant from LoBianco’s sergeant over Thanksgiving, but it’s not clear if the lieutenant asked him to write it, or if the sergeant sent it on his own.

The list used against Officer LoBianco to show sexual harassment included reference to a text with a crude line about genitalia. LoBianco says it was a direct quote from a rap song the officers had been joking about earlier that day, and the memo backs that up. He was also criticized for giving his sergeant gifts, such as meters to check for illegal window tint.

A full page of the four-page memo details allegations of sexual harassment, but the lieutenant admits the alleged target didn’t think it was sexual or harassment at all.

“Upon speaking with [the sergeant] about it, he has expressed that while the behavior is off and/or even weird, he does not feel like there is any sexual intent behind it, and therefore does not feel ‘harassed’ by it…I don’t think that there was any sexual intent behind it either, but more of his way of trying to connect.”

The lieutenant still suggested referring the case to internal affairs for a sexual harassment investigation.

“I am suffering the consequences due to misleading and false information,” LoBianco told The Reveal.

Lt. Petersen did call Officer LoBianco “still one of us,” and offered that he was an effective law enforcement officer. “While I cannot deny that Officer LoBianco is very committed to the job and does go above and beyond the call of duty, he does get too involved and allows his emotions to get the best of him often, and it seems like this job is truly all he has,” Lt. Petersen wrote.

Relieved of Duty

Officer LoBianco was summoned to a meeting in December where he was told to turn in his badge and gun. He says he was not told why, and police records do not show that the department informed LoBianco of the allegations against him.

LoBianco was assigned to various civilian positions within the police department over the next four months, including the video integration center and code enforcement. City records show supervisors continued to supply negative information about LoBianco, but it’s not clear if that information was offered independently or at the request of other city officials.

Officer LoBianco still had his personal, department-approved back-up pistol and a concealed carry permit, but he was counseled after clearing the weapon at work, and he was told to leave the gun at home. Among the negative reports from supervisors was that he was using binoculars to observe drug deals on the corner from the windows of the video integration center.

At the same time LoBianco was relieved of duty, he learned he had been approved to take APD’s investigator exam for a promotion. His requests for information from commanders about his duty status went unanswered, texts and police records show.

Unfit For Duty?

In late March of this year, commanders officially requested that Officer LoBianco be evaluated for fitness for duty.

The officials parroted items from the original list of concerns Lt. Petersen had written in December, and added that “these incidents span three different worksites,” and also referenced “apparent dishonesty.”

Those phrases ended up in the Fitness For Duty Evaluation (FFDE) report issued in April by Dr. Ifetayo Ojelade, who found Officer LoBianco unfit for duty.

Dr. Ojelade also suggested that, “continuing efforts towards empowering the examinee to function optimally would be unsuccessful.” In other words, there was nothing LoBianco could do to get his badge back, in her opinion.

Larry LoBianco was terminated by the city on April 30 for “failure to pass fitness for duty evaluation.”

LoBianco sent a text to Dr. Adrienne Bradford, the director of the city’s Psychological Services and Employee Assistance Program, who had cleared Officer LoBianco to return to duty after the 2016 shooting.

“They destroyed me,” LoBianco wrote in the text to Dr. Bradford. “I should have listened to you that time when you said that there were some people out to get me.”

Bradford responded, “I know it’s hurtful, I’m sorry!” LoBianco wrote back, “Well they are saying that it is the office of EAP who is saying I need to be terminated. I recorded the conversation.”

A week after he was terminated, LoBianco was reinstated without explanation. “The original dismissal paperwork provided you is null and void and will not be processed,” the city’s Human Resources Department wrote on May 8.

The same city that said LoBianco was unstable fired him, and unfired him, over an eight day period. “It shows that they don’t care” LoBianco said. “They don’t care.”

If LoBianco needed help, the city wasn’t helping him get it.

LoBianco was not given the psychologist’s evaluation, or even the diagnosis paragraph that is typically provided to other officers when they’re ruled unfit for duty, according to records reviewed by The Reveal.

LoBianco hired a lawyer and sought to get a copy of the psych report, and the documentation that Dr. Ojelade was given by the police department before his evaluation.

“EAP will not release a copy of the report to Officer LoBianco because of concerns that the report may be harmful to [his] mental health,” the city attorney wrote. “It is not EAP’s practice to share the report with anyone, including the officer.”

LoBianco’s attorney also requested many of the same records we did, but the city made him wait months for LoBianco’s own personnel file and other records.

In a strange twist, the same lieutenant who had referred LoBianco for psychological problems was supervising the records clerks who were denying LoBianco and his attorney the documents. Lt. Robert E. Petersen had been transferred to the department’s Information Services division after relieving LoBianco of duty.

LoBianco had to request the FFDE report directly from Dr. Ojelade through his own psychologist, as a medical record between providers.

The Fitness For Duty Evaluation

Larry LoBianco shared the Fitness For Duty Evaluation report with The Reveal.

Dr. Ojelade began her FFDE report by listing the concerns that were presented to her by the police department before she ever met LoBianco. She also referenced his half brother who is institutionalized for severe autism.

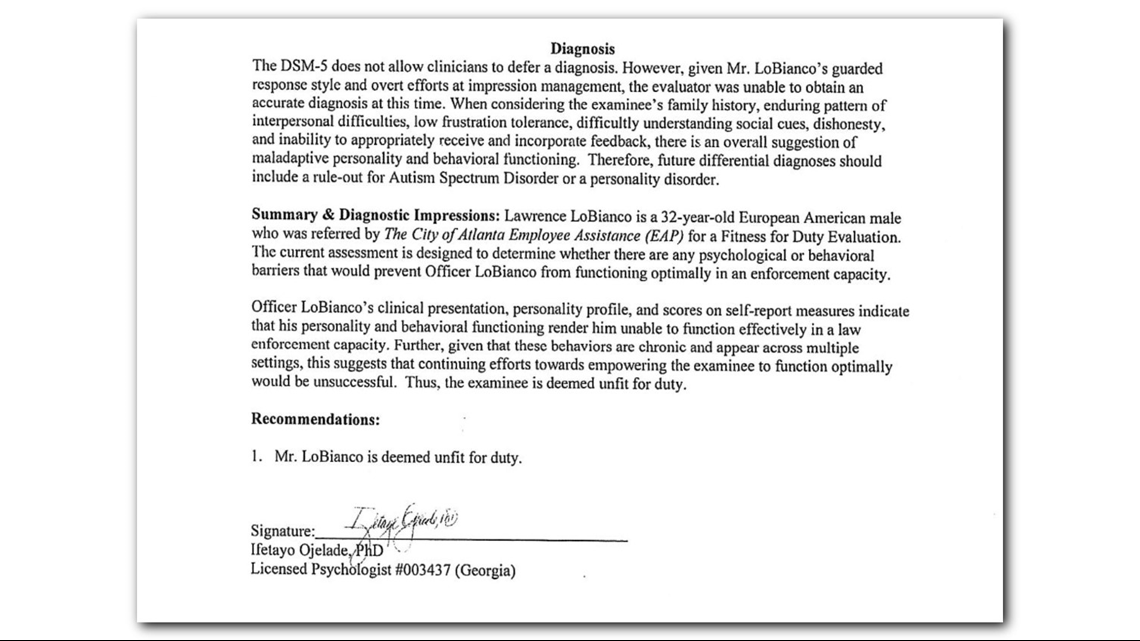

In the diagnosis section of her report, Dr. Ojelade wrote, “given Mr. LoBianco’s guarded response style and overt efforts at impression management, the evaluator was unable to obtain a diagnosis at this time.” She suggested he had, “maladaptive personality and behavioral functioning. Therefore, future differential diagnoses should include a rule-out for Autism Spectrum Disorder or a personality disorder.”

LoBianco said he was made to wait hours in the psychologist’s waiting room, where he was unaware office staff were watching him. Their observations made it into Dr. Ojelade’s report.

LoBianco was described in the official FFDE report as, “watching other clients in the lobby…as if he were evaluating them as suspects for a non-existent crime.”

As a result of Dr. Ojelade’s ruling, LoBianco wasn’t just blocked from working at APD, his Georgia peace officer certification was medically suspended by the state. His career as an officer was over.

“She destroyed my life,” LoBianco said.

Striking Similarities

The Reveal filed records requests for all adverse Fitness For Duty Evaluations in the Atlanta Police Department in recent years. Of the five officers ruled psychologically unfit, three were sent to Dr. Ifetayo Ojelade for their FFDEs. A fourth officer sent to Dr. Ojelade was cleared to return to duty, according to APD which supplied no records to us related to that officer’s case.

Unlike LoBianco, the two other officers ruled unfit by Dr. Ojelade were given their diagnosis paragraphs, but not the full reports. In the memos provided to us by Atlanta Police in response to our records requests, those diagnosis paragraphs were redacted.

The Reveal reached out to the two other officers and asked if they would be willing to provide the diagnoses that APD had kept hidden. The paragraphs provided to us by all three officers match in some places word-for-word which we have highlighted below.

Officer #1 FFDE Diagnosis

“Given [the officer’s] overt efforts at impression management, the evaluator was unable to obtain an accurate diagnosis. The examinee’s enduring pattern of behaviors in multiple settings…suggest maladaptive personality functioning. [The officer’s] clinical presentation, personality profile, and scores on self-report measures indicate her inability to be self-reflective, follow professional protocol, appropriately manage her anger, and accept corrective feedback render her unable to function effectively in a law enforcement capacity.”

Officer #2 FFDE Diagnosis

“[The officer’s] uncooperative behavior and overt efforts at impression management, the evaluator was unable to obtain an accurate diagnosis. The examinee’s enduring pattern of behaviors that include a chronic inability to be truthful, efforts to avoid abandonment, unstable relationships, and inability to receive feedback, suggest maladaptive personality functioning. [The officer’s] clinical presentation, personality profile, and scores on self-report measures indicate that her inability to be self-reflective, accept corrective actions, or engage in authentic relationships suggests she is unable to function effectively in a law enforcement capacity.”

Officer LoBianco’s FFDE Diagnosis

“Given Mr. LoBianco’s guarded response style and overt efforts at impression management, the evaluator was unable to obtain an accurate diagnosis at this time. When considering the examinee’s family history, pattern of interpersonal difficulties, low frustration tolerance, difficulty understanding social cues, and inability to appropriately receive and incorporate feedback, there is an overall suggestion of maladaptive personality and behavior functioning. Officer LoBianco’s clinical presentation, personality profile, and scores on self-report measures indicate that his personality and behavioral functioning render him unable to function effectively in a law enforcement capacity.”

OTHER NEWS: Turning a blind eye? Teen not alone in claims of sexual assault in Georgia youth detention center

Fit For Duty - LoBianco Cleared

Larry LoBianco went to his own psychologist for treatment and a second opinion.

Dr. David Raque, a psychologist with more than four decades of experience, was deeply critical of Dr. Ojelade’s methods and conclusions.

“Due to the fact that I did not have the additional information accorded Dr. Ojelade, I must conclude her report and findings were primarily based by the information the APD provided her because none of the tests she administered to Officer LoBianco offer a psychological explanation as to why he is not fit for duty,” Dr. Raque wrote in his FFDE report, clearing LoBianco to return to duty.

Dr. Raque also took issue with Dr. Ojelade’s report indicating LoBianco was sizing up other patients as suspects in the waiting room. “These interpretive comments do not make Officer LoBianco unfit for duty. As a professional, using statements from office staff do not stand as scientific, factually based conclusions to decided fitness for duty,” Dr. Raque wrote.

LoBianco was also diagnosed with dyslexia, to which Dr. Raque attributed supervisors’ concerns about LoBianco’s report writing skills. Dr. Raque also noted depression and anxiety, which he opined were caused by the acute stress the department and the city had placed on LoBianco over four months.

“When I read Dr. Ojelade’s report closely, I see none of the tests she administered support Officer LoBianco’s being fired," wrote Dr. Raque. "Based on my results, I recommend Officer LoBianco be immediately reinstated as an active police officer,” he concluded.

Out of an abundance of caution, LoBianco went to a third psychologist to get yet another opinion.

Dr. John Azar-Dickens, a psychologist and sworn police officer, wrote to LoBianco’s attorney, “…the initial fitness for duty done by APD’s psychologist is one of the worst I have ever seen…her interpretation of testing was bizarre…it’s as if she doesn’t even understand the test itself.

Dr. Azar-Dickens’ FFDE report determined LoBianco, “is found fit for duty and no specific concerns are identified related to his functioning in the role of an officer at this time.”

The third psychologist did diagnose LoBianco with “Adjustment Disorder with Anxiety,” and some obsessive-compulsive traits, but these were interpreted as minor issues that did not prevent him from serving as a police officer.

Dr. Azar-Dickens also determined, “while Officer LoBianco is found fit for duty, he may be better suited for a smaller department that is less chaotic, and which has a smaller command structure.”

No Appeals - No Second Opinions

Despite the trauma the city put him through, LoBianco still wanted to go back to the Atlanta Police Department as an officer.

His attorney sent the city the new FFDE report clearing LoBianco to return to full duty.

The city refused to accept it.

“The second opinion for fitness for duty is of no consequence to the department because the City’s Code, Section 114-380, indicates that an employee shall not be entitled to a second opinion,” the city’s HR department wrote back.

The ordinance was amended by city council in 2017. Prior to that, any officer ruled unfit would be entitled to an appeals process, including a panel of psychologists who would make a final recommendation. Now, only officers with physical fitness issues are allowed an appeal and panel review.

The opinion of the city’s chosen outside psychologist is final. No exceptions.

“What kind of leadership is that? What kind of person are you? That’s cruel,” LoBianco said.

The same city ordinance that prohibits second opinions also requires the city to offer other, civilian positions with the city for officers ruled unfit for police duty. LoBianco is currently working for the city’s zoning code enforcement unit, according to him at a vastly reduced level of pay.

The former officer says he was offered a list of disappointing options including a job as a custodian for the city.

Georgia POST (Peace Officer Standards and Training) accepted the second opinion clearing LoBianco to return to duty, and POST fully reinstated his certification once he updated the mandatory training he missed during his relief from duty.

LoBianco is currently cleared to work for any police department in Georgia. Any department except Atlanta.

One of the two other officers kicked off the force after evaluations by Dr. Ojelade is currently working for a police department in a neighboring jurisdiction.

Dr. Ojelade and The City of Atlanta

We reached out to Dr. Ojelade and twice requested an interview. We made it clear we would be investigating her methods. Through her office staff, Dr. Ojelade declined our request and offered no comment.

Similarly, we asked for interviews with Atlanta’s mayor and police chief. Both refused.

Carlos Campos, director of the Atlanta Police Department’s Public Affairs Unit, gave us this statement: “The fitness for duty process employed by the Atlanta Police Department is outlined in the City of Atlanta’s Code of Ordinances. This is a grossly inaccurate mischaracterization of APD standards and procedures designed to ensure the safety of the public and law enforcement. This attack on a medical professional’s objectivity is shameful and we stand behind the process and the professionals who perform evaluations.”

We got no reply when we asked in writing what, if anything, we had provided to the city was inaccurate.

The day after we received the written statement from the city, the website for Dr. Ojelade’s practice, A Healing Paradigm, included a new copyright warning.

Dr. Ojelade’s Twitter and Facebook accounts were also deleted.

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country. It airs Sunday nights at 6 on 11Alive.