He died in an Atlanta airport parking lot. 22 minutes after 911 call, first responders started CPR

A man died in an airport parking lot while waiting 22 minutes for CPR. The airport’s 911 center doesn’t have protocols for providing pre-arrival instructions.

The busiest airport in the nation has no protocol for providing CPR instructions to 911 callers during life-and-death medical emergencies.

Before COVID-19, Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport was the busiest in the world. That’s one reason the airport has its own dedicated 911 center. Calls from the airport are answered by multiple 911 centers in four cities and two counties, but all have a policy of transferring those calls to the airport’s Centralized Command and Control Center, or C4.

Thomas Lawson suffered an apparent heart attack in the South Economy parking lot on November 20, 2020. The 62-year-old retired Marine from Flowery Branch, stood up from his car, grabbed his chest, and said to his wife, “something’s wrong.”

Those were the last words Ruth Lawson would ever hear her husband speak.

“He took three very loud gasps of air, spaced apart, and never breathed again,” Ruth Lawson said. Thomas had previously survived heart surgery.

Ruth immediately called 911. She had no idea that another 22 minutes would pass before an airport firefighter would start CPR on her lifeless husband.

“It feels like forever when you're sitting there watching your loved one die in front of you,” Ruth explained.

Even though the South Economy parking lot is in College Park in Fulton County, her call was picked up by a cell tower on the Clayton County side of the terminal.

Clayton County 911 trains its operators to be Emergency Medical Dispatchers, or EMDs. While the operator who answered the call that morning was not yet a certified EMD, there was one available right next to her who could have provided CPR instructions.

Following policy, the operator transferred the call to the airport’s 911 center after 47 seconds.

‘We don’t have any dispatchers that are EMD certified,” the airport’s 911 director, Augustus Hudson, wrote in an internal email to clerks responding to a records request from 11Alive's investigative team, The Reveal.

“We don’t do EMD here,” Hudson wrote.

Instead of detailed instructions to help her husband breathe again, or to do chest compressions, Ruth was asked a series of questions she called “small talk” while waiting for the ambulance.

“How long have you been together?,” the dispatcher asked Ruth. “Are you from here?”

None of the questions was directed toward helping Ruth save her husband’s life.

Four options, none used

Several states — and major airports — require Emergency Medical Dispatcher certification. Georgia does not.

In fact, Georgia does not require any in-service training at all for 911 operators, even years or decades after they pass the initial 40-hour basic course.

Across the state, 911 centers are free to use any of four standard protocols to handle medical calls, or none at all.

- The first is Emergency Medical Dispatch, which requires specialized training and certification. Centers that use EMD subscribe to specialized index cards or software that guide dispatchers through a series of questions and instructions, such as telling callers how to do CPR while the ambulance is on the way.

- The second protocol is Telecommunicator CPR, or T-CPR. This is training pushed by the American Heart Association, that is less demanding and time consuming than full EMD certification, but still allows dispatchers to give some life-saving advice over the phone.

- The third protocol involves staffing a 911 center with EMTs or paramedics who can take over a medical call from a dispatcher to offer pre-arrival instructions.

- The fourth protocol is to transfer a 911 call to a secondary 911 center staffed by medical personnel. This is the method used by Atlanta’s main 911 center run by the police department. Medical calls everywhere in Atlanta but the airport are transferred to Grady EMS.

RELATED: Lost on the Line: Why 911 is broken

Atlanta’s airport, also a city department, uses none of these medical pre-arrival instruction protocols. All a 911 operator at the airport can do is dispatch medic units and stay on the line to keep the caller calm.

Even if a 911 operator at the airport knows CPR or has previous medical training, they are prohibited from giving life-saving instructions to 911 callers.

“They're not trained to provide CPR instructions over the phone,” Hudson said.

Major airports across the nation, Like DFW in Dallas, require EMD and provide pre-arrival instructions over the phone during medical calls.

22 minutes until CPR

A series of events delayed the ambulance sent to help Thomas Lawson.

First, the transfer from Clayton 911 to the airport cost 47 precious seconds. Four minutes after Ruth Lawson first dialed 911, the airport ambulance reported a mechanical delay. Eleven minutes into the call, the ambulance was delayed at an airport security gate.

Meanwhile Ruth told dispatchers that her husband was “white as a sheet…I can’t feel a pulse in his neck.”

“You have to be blind to not realize that someone is really leaving when they stop breathing, and if you don't get here soon enough, he will never breathe again,” she told The Reveal investigators.

Some 17 minutes after Ruth Lawson called 911, the ambulance missed the turn into the South Economy parking lot.

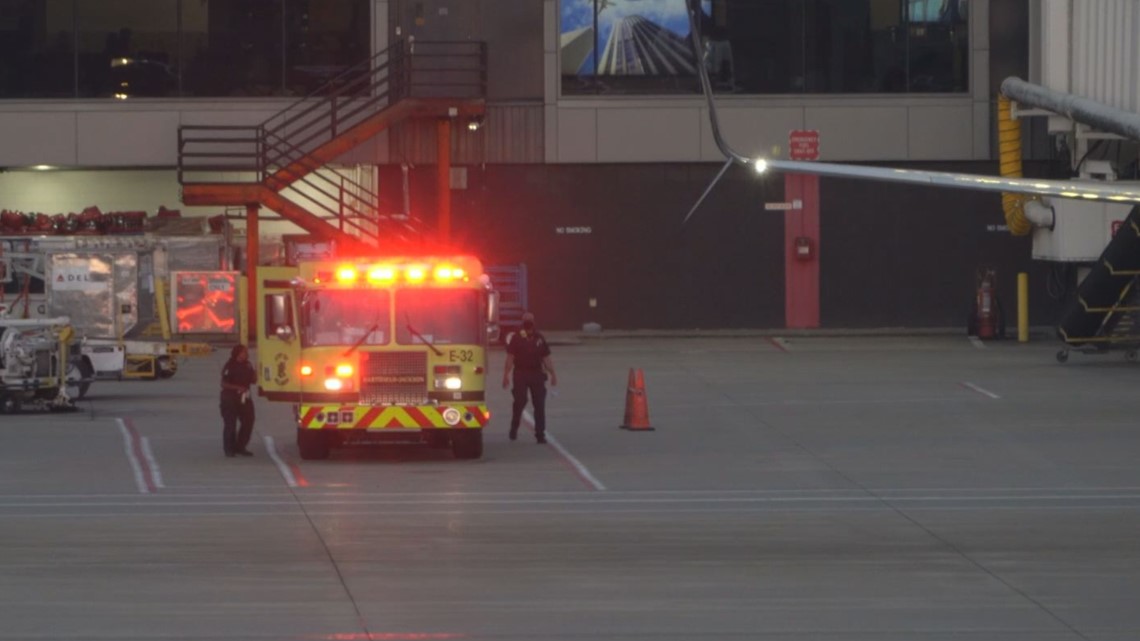

“We’re at the South Terminal right now. Should we go back around?,” the ambulance crew asked Engine 32, which had just pulled into the lot. Engine 32 responded, “yeah, you’ll have to go all the way back around and come in on the far side by the cell phone lot.”

Engine 32 reported CPR in progress at 11:05 a.m. Ruth had called for help at 10:43 a.m. — 22 minutes earlier.

If Thomas Lawson had collapsed on the tiny grass airstrip closest to his home in Flowery Branch, instead of at the busiest airport in the nation, his wife Ruth would likely have been given instructions to do CPR.

That’s because every 911 operator in mostly-rural Hall County is certified as an emergency medical dispatcher.

“Listen carefully. I’m going to tell you how to do chest compressions,” a Hall County EMD-certified dispatcher recently told a 911 caller.

“Pump the chest, hard and fast, at least twice per second, and at least two inches deep! We’re going to do this at least 600 times until help can take over,” the dispatcher directed.

After counting along with the dispatcher four compressions at a time, the caller said, “he’s got a pulse! He’s breathing!”

This kind of standardized pre-arrival instruction saves lives across the nation every single day, including in Georgia cities like Alpharetta, which also uses EMD.

DISPATCHER COULDN'T USE TRAINING

The operator who answered Ruth Lawson’s call had been a certified Emergency Medical Dispatcher for years, at least until she got hired by the airport.

Personnel records obtained by The Reveal show the airport dispatcher was previously the EMD manager for Fulton County’s 911 center, overseeing training and reviewing medical calls for accuracy.

In 2018, while still employed with Fulton County 911 as a higher-level EMD-Q, the dispatcher who would later answer Ruth’s call for help had co-authored a comprehensive study confirming the efficacy and accuracy of EMD pre-arrival instructions.

She was hired by the airport’s 911 center in May 2020, just six months before Thomas Lawson could have used her help.

“She could not have helped here because we don't have an EMD program here,” Augustus Hudson said. “So she's not authorized to provide those type of instructions,” he added.

The airport’s part of Ruth’s 911 call lasted 17 minutes and 55 seconds. Because the dispatcher was prohibited from sharing any medical instructions or CPR, she had no choice but to engage Ruth Lawson in small talk, which included a 40-second exchange about the origin of the dispatcher’s name:

Ruth Lawson: “I’m sorry, I missed your name.”

Airport Dispatcher: “My name is Miyoshi.”

Ruth Lawson: “OK, that’s an interesting name, where is it…”

Airport Dispatcher: “(laugh) it is a, it’s a Japanese name, um…”

Ruth Lawson: “OK.”

Airport Dispatcher: “I’m not a military brat and my mom didn’t travel. My parents didn’t travel. I was supposed to be born a boy, but I was born a female. So my mom had a male name. But she was watching a sitcom, and one of the housewives’ names was Miyoshi and that’s how I got her name.”

Ruth Lawson: “OK…”

Airport Dispatcher: “(laughing)”

The airport’s 911 director told us his team provided the “best service,” that it was a “good call,” and the dispatcher did an “excellent job.” He could not tell us if 22 minutes from 911 call to CPR was a good response time or not.

An internal email obtained by The Reveal through a public records request shows airport management considered the entire response “professional, conscientious,” and in the case of the dispatcher, “empathetic.”

In that same email from Andrew Gobeil, the airport’s interim director of policy and communications, told other managers that he was concerned The Reveal was, “more interested in pursuing a sensational segment rather than a true journalistic piece. That being said, not offering an on-camera response could make the airport look insensitive to the events surrounding Mr. Lawson’s death.”

Gobeil went on to offer to do the interview himself, instead of the 911 managers, whom he described as “experts in their respective fields, which do not include facing belligerent questions from a television presenter.”

Gobeil interrupted our time-limited interview with the 911 director outside the airport after we asked about the valuable seconds consumed by the origin of the dispatcher’s name.

“I don't want you to criticize the dispatcher for talking about her name, talking about her parents,” Gobeil said off-camera when interrupting. “She was doing the best she could to maintain calm, to do everything she could to make sure Mrs. Lawson was was taken care of. And this was not some flighty dispatcher who was unprofessional.”

When The Reveal's Chief Investigator Brendan Keefe asked, “have we said that?,” Gobeil replied, “the implication that you're trying to give is that she was not doing an excellent job.”

The Reveal requested a copy of the airport’s own phone recording of our interview, which would have captured Gobeil’s interruption on camera, but the airport wrote that the video could not be released without a TSA review, citing a federal regulation about sensitive security information at airports.

No medical training for 911 center

Hudson, the airport’s 911 director, repeatedly deferred to the “medical community” at the airport, saying “right now, EMD is not the recommendation.”

The airport’s Emergency Medical Services Director, Chief Christopher Collins with Atlanta Fire & Rescue, told 11Alive that 45 people have required CPR or suffered cardiac arrest at the airport since the beginning of 2019.

“Seven of those people were brought back, discharged from the hospital,” Collins said.

Does that mean 38 have died in a little more than two years? The airport and Collins wouldn’t say, and a spreadsheet sent by the airport didn’t help answer that question.

Atlanta’s airport has Automated External Defibrillators, or AEDs, deployed throughout the terminal and passenger concourses. They have been used to save lives, but the airport said weather conditions don’t allow AEDs to be stationed in the sprawling airport parking lots.

Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is the third leading cause of death in the United States in non-COVID years, according to the American Heart Association, which also said that every minute of delay starting CPR leads to a 10% reduction in the chance of survival.

The average total response time at Atlanta’s airport in 2020, from first call to rescue units arriving on scene, was 11 minutes and 48 seconds. That is much higher than surrounding agencies and the national standard.

“In many instances, the responding units have to go around the airport, get through the traffic, get through security,” Collins said. “Once they get through security and all the rest of that, they have to make it to where the patient is.”

Collins described the airport as “skyscrapers laying down,” with all the complexities of getting rescuers to the 80th floor.

Multiple 911 directors contacted by The Reveal said the airport’s extended response time makes medical pre-arrival instructions all that more critical to saving lives.

Fulton County 911 and Clayton County 911 answer emergency calls from the airport, and both use Emergency Medical Dispatch. Both also transfer calls to the airport’s 911 center, from centers that could offer pre-arrival instructions to one that cannot.

Four cities also pick up wireless 911 calls from the airport. Atlanta 911 and East Point 911 transfer medical calls to EMS operators at Grady Hospital. College Park uses a hybrid of EMD and transfers to Grady. Only Hapeville has no medical pre-arrival protocol, but the 911 director said their average EMS response time is around two minutes.

“Pre-arrival instructions always do help save lives,” Collins said, but added, “in this environment, it creates a challenge.”

The airport once had paramedics or EMTs on hand in the 911 center to provide pre-arrival instructions, according to Collins.

“That's something we can take a look at again, but right now it's not possible,” because of staffing shortages throughout Atlanta Fire & Rescue, the chief said.

Final destination

Tom Lawson was supposed to fly to Los Angeles with his wife to see Ruth’s father last November.

Instead, he reached his final destination when he parked at space 60-D in the South Economy lot at Hartsfield Jackson International Airport.

Now his widow, Ruth, is packing up the home where they raised their two boys in Flowery Branch.

“I can no longer live in the residence that I'm in, because of the incident,” Ruth said.

“The house is too big and needs a family.”

The Reveal is an investigative show exposing inequality, injustice, and ineptitude created by people in power throughout Georgia and across the country.

MORE FROM THE REVEAL:

Cancer causing chemical found in Ga. drinking water remains unregulated five years after EPA warning