Risking their jobs and retaliation, current and former employees at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are talking about documented discrimination complaints with 11Alive News.

The list of complaints, submitted to the agency’s Equal Employment Opportunity office over the past decade, was provided to 11Alive Investigator Andy Pierrotti this past May. There are at least 944 of them.

DIAGNOSING DISCRIMINATION | Read Part II

DIAGNOSING DISCRIMINATION | Read Part III

The disclosure came after filing a Freedom of Information Request from 11Alive, which asked for discrimination complaint numbers. Instead, someone at the agency handed over a list identifying each employee and their complaint. The CDC says it was an accident.

In a letter sent by deputy chief counsel for the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Constance Kossally asked 11Alive to “destroy all copies of the information, including electronic copies.” 11Alive declined, but chose to only identify CDC employees who agreed to share their stories.

Whether the disclosure was an accident or intentional, it severed confidentiality agreements with many employees who settled discrimination complaints. The result, many employees believe, allows them to discuss details about their complaints typically kept secret from the public.

Stories of discrimination

Anjella Johnson-Hooker is one of those employees who filed a complaint.

She was a top management official at the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD). At the time, Johnson-Hooker was responsible for a $5 billion budget and 1,300 employees.

"It was exciting," she recalled. "You never knew really what your day was going to hold." At the time, she was the only African-American in a senior leadership position at NCIRD.

Throughout her 17-year career, the agency recognized her with awards and accomplishments. One of those achievements included creating a system to track immunizations and vaccines across the world, a project the CDC struggled to launch for eight years. Johnson-Hooker told 11Alive she got it up and running in a year.

"I’ll never forget," she said. "Even senior leaders did not think it could be done, because it hadn’t been done."

Six years later, new CDC management came onboard, and in 2016, Johnson-Hooker was forced to re-apply for her job. Despite a stellar record, management told her they were looking for fresh blood.

She learned she lost her post through an email from human resources that read in part, “The hiring office has…decided not to use the certificate of highly qualified candidates.”

The email not only confirmed the CDC knew Johnson-Hooker was the best candidate, it acknowledged her replacement did not meet the agency’s requirements to be among the list of the most qualified applicants, which she later learned was a white colleague.

Johnson-Hooker still works at the agency, but she said she’s no longer invited to strategic meetings and has no voice in an agency she used to run.

“It’s like being stabbed with a knife," she explained. "So, you draw your own conclusions. But for me, when I look at it, it looked like racism."

11Alive Investigator Andy Pierrotti uncovered CDC leadership has known about claims of wide-spread discrimination for years. According to a 2012 CDC diversity and inclusion study, about half of the employees of color surveyed believe it’s a problem. Survey respondents told auditors, “highly qualified minorities are often overlooked for promotions.”

Four years later, the same diversity report showed minority sentiment had worsened. “[African-Americans] are the forgotten people when it comes to promotions,” wrote the study’s authors. According to the 2015/2016 audit, “it’s getting worse with respect to…retaining a diverse workforce.”

MORE | Read the 2015/2016 audit

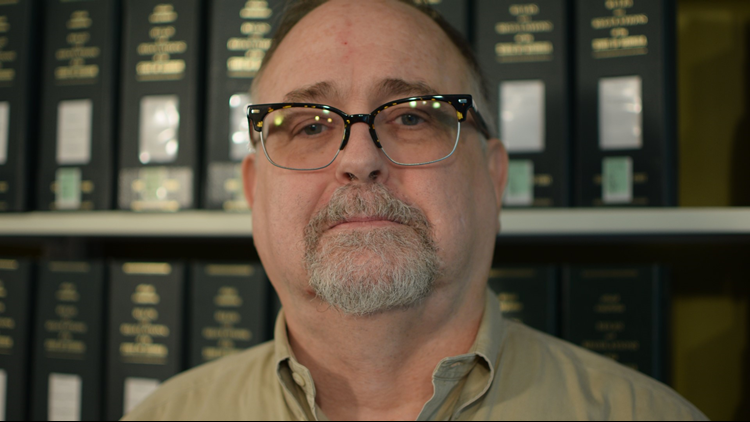

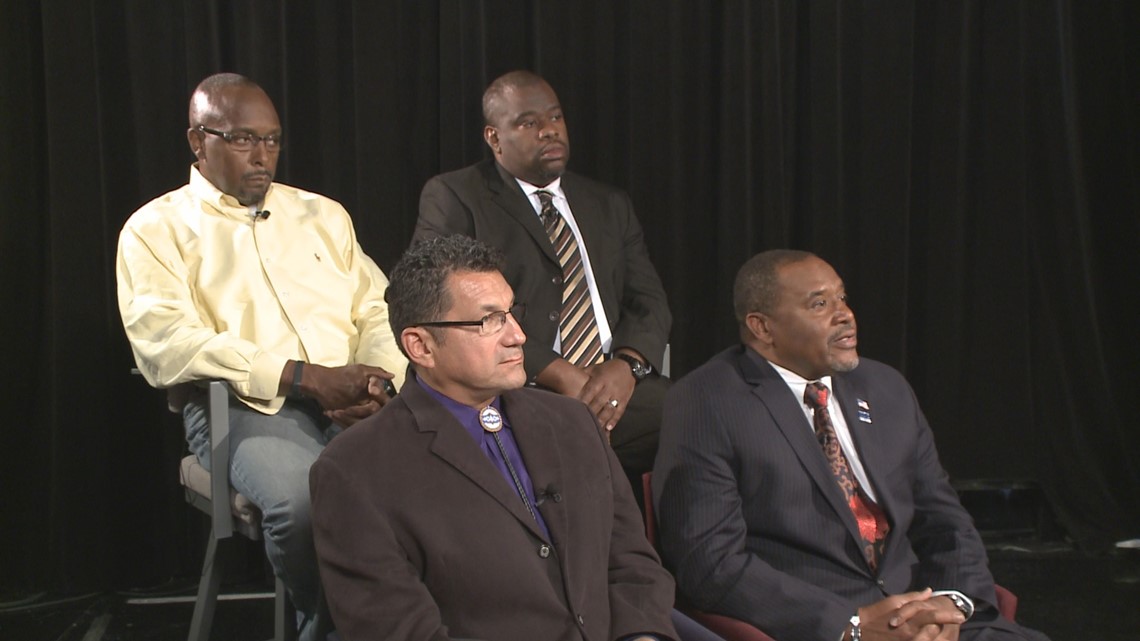

Clement Craddock agrees. As the CDC’s former emergency response manager, he was responsible for keeping agency employees safe across the globe. He says the agency sent him to Harvard and Georgia Tech for training over the past several years, costing taxpayers hundreds of thousands of dollars.

Employees of the CDC speak out about their claims of discrimination

In his discrimination complaint, he claims CDC replaced him with someone who had far less experience. Craddock’s current job description mirrors that of an over-paid hall monitor -- one that earns more than $130,000 a year.

“They want me to walk the hallways, walk the stairwells, look behind the doors to make sure they’re clear,” Craddock said. "That’s fraud, waste and abuse.”

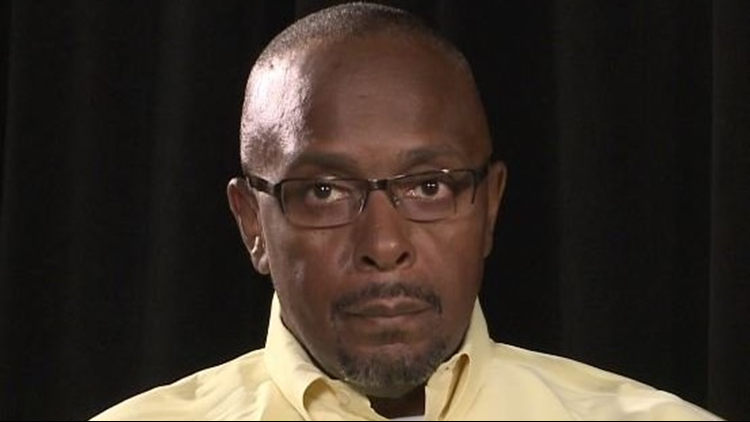

Carlton Duncan spent 35 years at the CDC and ended his career in a top leadership role. As deputy chief operating officer, he oversaw all domestic and international operations. He said all of his performance evaluations were positive and he often earned bonuses each year.

When his boss retired, he claims the agency never considered him for the job, even though policy mandates the position be filled through a competitive process.

“I was not interviewed. The position was never discussed with me. I never had an opportunity to compete for it, “ Duncan said. “The excuse I was given was, [CDC management] didn’t know who I was.”

Duncan settled a discrimination suit in 2011. Until now, he’s never discussed his complaint.

"I believe the issues at the CDC are clearly institutionalized and systemic," Duncan said. He retired in 2011.

When Rodrick Frazier joined the CDC in 2003, he thought he had landed his dream job.

“I was very passionate about that job for several years,” said Frazier, a health scientist. In 2008, he received a doctorate in naturopathy, a form of alternative medicine, while working at the agency.

Throughout his 18-year career, he’s worked in several divisions, including the Office in Infectious Diseases, as a safety manager.

In 2005, he filed a discrimination complaint after he says a manager attempted to force he and another black colleague out of the office.

“My motive for filing was, I don’t want any other young African-American male or female coming to this agency to have to deal with what I’m dealing with right now,” Frazier said. He settled the claim in 2007.

Frazier left that division and started working with a team that trains state coordinators in biological and chemical terrorism safety, where he eventually became a branch chief.

In 2014, his supervisor called him while he was at a hospital, waiting on the birth his daughter while on leave. Frazier said he was told his position was eliminated due to a re-organization. He doesn’t buy that excuse.

"I was the only branch chief not allowed to hire my own staff, couldn’t control my own budget," Frazier relayed. "My Caucasian colleagues were able to do so, but not me."

Since 2014, he’s filed two additional complaints related to retaliation claims. Both are both still pending.

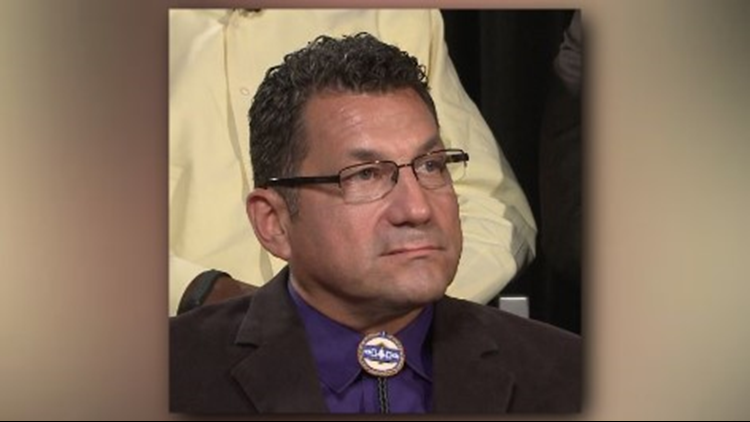

Dean Seneca, a health scientist and Native-American, has also filed numerous discrimination claims. He said CDC management has limited his ability to work on tribal issues.

“How inappropriate is that that I happen to be American Indian?” Seneca said. “The nation really needs to know what’s really going on at CDC.“

The 11Alive Investigators requested an interview with two members of the agency’s leadership team: newly appointed CDC Director Brenda Fitzgerald, and chief operating officer Sherri Burger, who has held the position since 2010. Both declined interviews. Both are white woman.

Many employees with pending or settled complaints believe the CDC’s Equality Employment Opportunity office is part of the problem. The EEO office is responsible for investigating discrimination complaints.

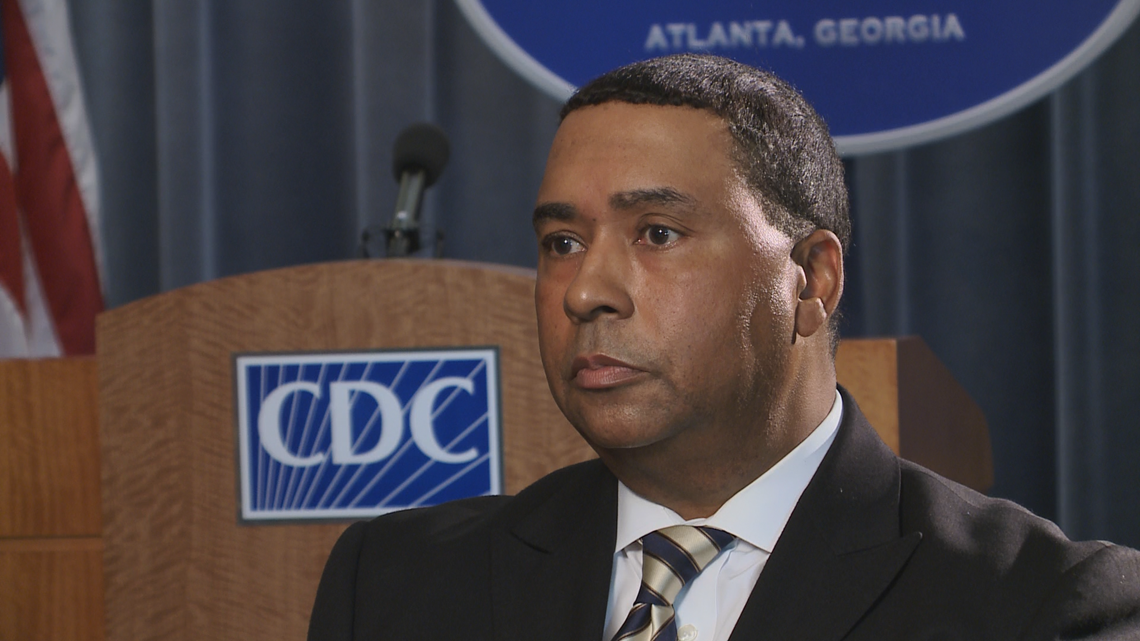

Its director, Reginald Mebane, doesn’t believe discrimination at the agency is systemic, but he did acknowledge the diversity reports’ findings.

“I can say honestly that we are concerned about the results of the audit,” Mebane told 11Alive. “I can understand and appreciate the sentiment, but the facts say otherwise."

Mebane said his office’s handling of discrimination complaints has improved over the past four years.

“We hold ourselves accountable to the EEO process, that is very tightly regulated and ensures that when we make decisions, about who gets promoted, or who gets trained, who gets paid, that those decisions go through a rigorous analysis," he said.

When asked why he believes current employees are risking potential retaliation for speaking out, Mebane, an African-American, called race a “very emotional” issue for employees.

“When an employee goes through the process of EEO and they don’t necessarily get the desired outcome, they feel very strongly about that,” Mebane said.

About a week after the interview, Mebane emailed the entire agency to notify employees about 11Alive’s future investigations and his decision to participate.

“We expect the tone of the series to be critical of CDC, and we wanted you to hear from us first,” Mebane wrote. “I agreed to an interview with the television station to help viewers understand how CDC’s equal opportunity employment system works and to offer general information.”

Cost to taxpayers

Records disclosed to 11Alive show the agency settled dozens of discrimination complaints, costing millions of tax dollars. Since 2007, the agency has paid out at least $4 million to 154 current and former employees.

But the figure is likely more, because many employees 11Alive tracked down said their settlements were higher than reported on the disclosure, which the agency requested the TV station to destroy.

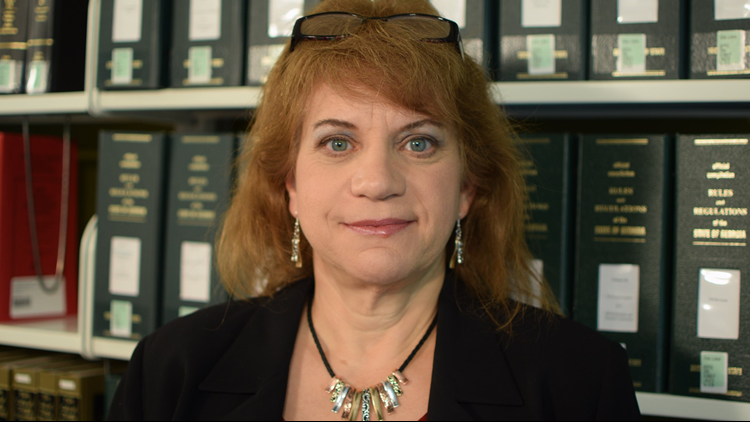

Tammy Corley received the highest settlement in the agency’s history. The former CDC behavioral scientist filed a disability discrimination complaint in 2012, which claims supervisors retaliated against her after she requested to change her work schedule to accommodate her documented delayed sleep phase syndrome.

Despite positive markings in every criteria in her last annual performance evaluation, Corley's supervisor terminated her for attendance violations. In 2014, the agency paid her $565,000 to settle her complaint. Corley now lives in New Zealand.

"A single person decided to discriminate against me when I did nothing wrong. As a result of defending myself, the career I spent a lifetime building was destroyed,” Corley wrote in an email to 11Alive. "They destroyed my life, so when you win against the CDC, you still lose."

How the CDC compares

It’s difficult to compare discrimination complaint numbers with other agencies because the U.S. government does not keep good records of federal employee disputes. By law, agencies are required to report figures to the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

When 11Alive sent a Freedom of Information Request to the agency requesting complaint numbers, the EEOC provided a link to a spreadsheet. Of the 152 federal agencies on the list, 40 reported “NRF” or "No Report Filed," where complaint data should be posted.

"While EEOC [regulations] require each federal agency to report federal sector EEO complaint data, some of the listed NRF agencies may be of a larger federal agency and their data may be reported elsewhere as part of the larger organization,” said James Ryan, an EEOC spokesperson.

Follow the series "Diagnosing Discrimination"

Part I: Monday, Oct. 30 – The Disclosure: An unprecedented number of CDC employees come forward with details about their complaints of discrimination.

Part II: Tuesday, Oct. 31 – Disability Discrimination: The CDC admits it breaks the law by not providing accommodations for its most vulnerable employees.

Part III: Wednesday, Nov. 1 – Retaliation: Employees discuss retaliation after filing discrimination complaints; the CDC keeps the results of discrimination secret.