Family of Brianna Grier says daughter would be alive today if Hancock County implemented new law

The law went into effect July 1, two weeks before deputies responded to Grier having a mental health episode. However, the new legislation has no mandate.

'Could this be addressed ahead of time?'

State legislators praised several laws aimed at helping Georgia respond to mental health this year.

One of them was the "Co-Responder law "that took effect July 1, encouraging law enforcement to team up with mental health counselors, but two months later, most counties have yet to create one of these co-responder teams.

13 Investigates’ Ashlyn Webb sat down with one family who says their daughter would be alive today if a mental-health professional was there to help.

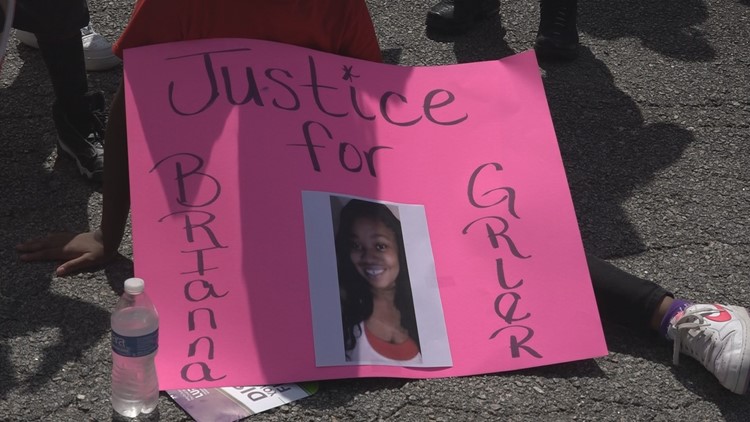

Hancock County made national news when body camera video was released showing deputies responding to 28-year-old Brianna Grier having a schizophrenic episode on July 15. A call for help from her parents ended in tragedy. The Georgia Bureau of Investigation says Grier fatally injured her head when she fell out of a deputy cruiser.

But to tell her story fully, Grier’s family says you have to go back to 2012.

“She was just 100 percent Brianna. She was just a smart, loving, caring human being,” said Mary Grier.

In 2012, Brianna Grier graduated from Hancock County High School with big and bright plans. That year, she went on to Fort Valley State University, studying to be a veterinarian.

“Smart as a whip. Smart as a whip,” Mary said.

But while at school, Brianna started showing signs of schizophrenia.

“With a condition like that, you don’t know which way they’re going to go. Who’s telling them what they’re going to do? …You don’t know if they’re going to hurt themselves or hurt you,” Marvin Grier said.

Marvin and Mary Grier say they’re daughter moved back home. The closest place for her to receive care for schizophrenia from her home in Hancock County was a 40-minute drive away in Milledgeville.

“That’s too long a distance,” Marvin said, especially when she was having an episode, her parents say.

“That’s why we always called 911. That was our only resource here…911. We didn’t have no other number to call,” Marvin said.

The Griers say usually EMTs would come to their home along with deputies.

But on July 15, only two Hancock County deputies responded when Brianna was suffering from another episode. They arrested her for public drunkenness.

Deputies' body camera video shows Brianna as they carry her to the cruiser. She yells, "Bring out your breathalyzer,” and, “I ain't broke no law."

The Griers say their daughter was not treated like she was having a schizophrenic episode.

“[She was treated] like a criminal,” Marvin said.

This time, the Griers' call for help ended differently.

"How'd she jump out of the car? There's got to be a lock in the back,” a Hancock County deputy said. “We got to do a report."

13 Investigates asked the Griers if they believed the outcome on July 15 would have been different if a mental health counselor was there along with police. Both said yes.

“Most definitely,” Marvin said. “We need training for the police officers.. We need someone to assist them if they don’t get the training in it. We need someone to assist them that can deal with people who have mental challenges.”

A law that went into effect July 1, 15 days before the sheriff’s office responded to the Griers' home, aims to do just that--get counselors on the ground with law enforcement responding to mental health calls.

State Senator Ben Watson was the primary sponsor for the bill.

“This was to require a framework to allow this to happen, to encourage this to happen, not a mandate,” Watson said.

It’s a law with no mandate. It’s up to counties to choose whether to implement and to find the funding.

“I think it’s something that will be a great return on investment when it comes to saving the county’s money. It’s going to be the right thing. It’s going to be patients out of emergency rooms and out of jails and putting them in places where they need to be,” Watson said.

Even if a county chooses to create a co-responder team, they then have to deal with finding mental health counselors that can respond. The state tried to resolve that last legislative session by putting in place tax credits and incentives.

The Griers say that doesn't give immediate help to families like theirs, trying to get their loved ones care closer to home.

“I get it. It's tough. Transportation is tough. Living in poverty is tough. There's no doubt about that, but this is offering a framework to allow that. This is not the panacea by any means. This is not going to cure mental health by any means,” Watson said.

Watson says it's not up to the state to provide mental health resources. It's just there as a safety net, he says.

“The question is, 'Why are they there? Could this be addressed ahead of time?' Certainly, it should have been,” Watson said. “I would say it's really the family's responsibility to get that person help.”

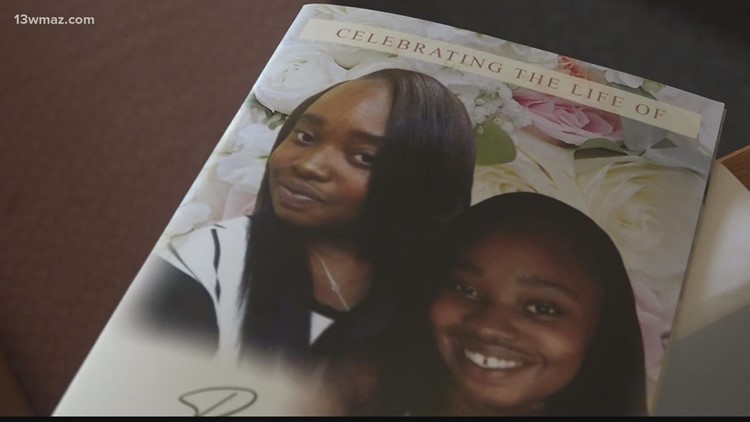

PHOTOS: Grier family says Brianna would be alive if Hancock County implemented new law

But the Griers say they did all they could.

“Everything we could handle, and we'd do it all over again if we had to,” Mary said.

They added that the state needs to step up to bridge the gap in access.

“We need resources,” Marvin said.

15 agencies out of Georgia's 159 counties have created co-responder teams, according to state Senator Ben Watson. Many relied on federal grants to build the programs.

U.S. Senator Jon Ossoff says a new federal law he sponsored will help fund these teams.

His office could not provide estimates for how much money will come to Georgia.

They say it will vary each budget year based on need.