The auto industry could be reshaped by a repossession device for cars. “Starter interrupter” technology makes a vehicle impossible to start after the owner misses a payment, but federal regulators are asking questions about how at least one auto finance company uses the equipment, reports CBS News correspondent Anna Werner.

Willie Conner needs a kidney transplant and gets dialysis five times a week. She needed a car, but she and her husband didn’t have a lot of money, so Car Credit City offering guaranteed credit sounded good.

“They made it easy, you know. Come on in, we’ll give you a car. Regardless of your credit,” Conner said.

That dealership is what’s known as a “buy here, pay here” auto lender, which means the dealership does its own financing on transactions. The price was high: a 2007 Chevy with more than 100,000 miles would cost them over $21,000 after payments at almost 29 percent interest, nearly six times the national average.

“But I had to get to dialysis. I have to get there or I don’t live,” Conner said.

Then one day in 2012, she came out of the treatment center and found the car wouldn’t start. Why? She said even though she had told them she would be a few days late on the payment, the dealer had turned the car off.

“At dialysis of all places. They cut my car off,” Conner said.

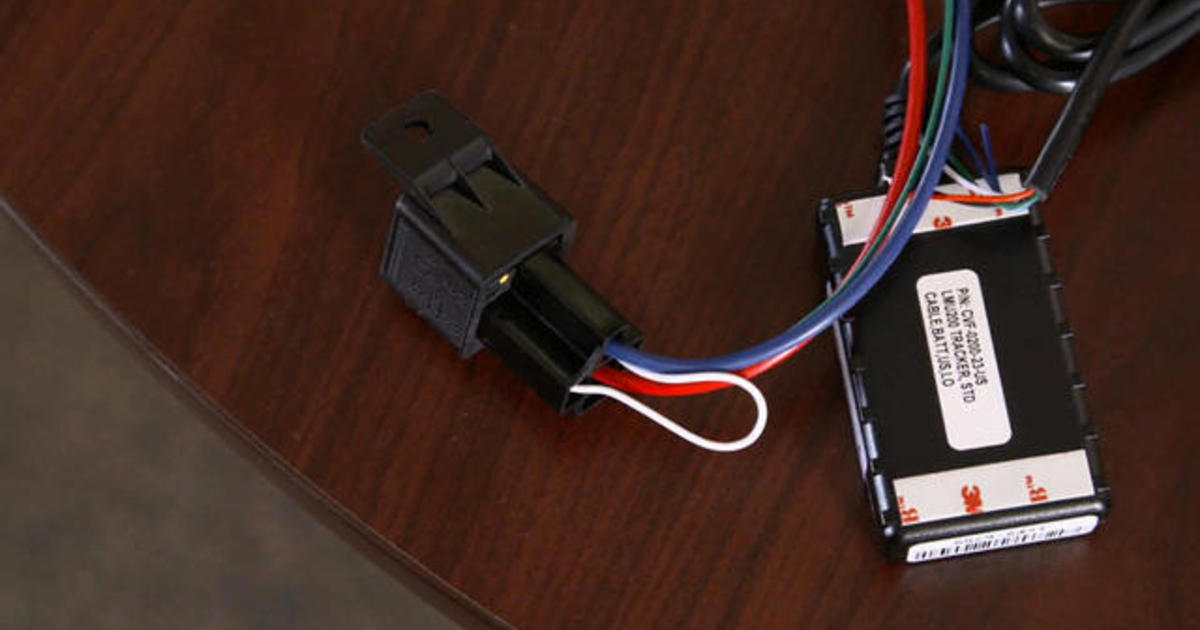

How? It’s something called a “starter interrupter,” technology that, combined with GPS tracking, allows a dealer to remotely track the location of a car, then disable it from starting as long as the car’s not moving.

Conner was left stranded.

“What did that make you feel like?” Werner asked.

“Like I was failing at everything. Everything. My health. My life,” Conner said. “Everything was a failure.”

Phoenix former car dealer Michael Fischer sells the devices. He says they’re needed because many buyers with poor credit default on the high-interest loans.

“It is a very risky business. I’ve been there. I lost a lot of cars which I didn’t even think was possible. I could find the customer. I just couldn’t find the car,” Fischer said.

But there are no federal laws on how to disclose or use the devices, and just four states have any regulations.

Chris Kukla with the Center for Responsible Lending said there are safety concerns.

“You’re on your way to pick your kids up, you stop at the store and suddenly you can’t start your car and your kids are left alone at a school,” Kukla said. “Or there are certainly stories of families where the mom was trying to get a kid to the emergency room and they got out to the driveway and couldn’t start their car.”

Even Fischer said, “The dealership should at least know where the vehicle is at when they’re shutting it off.”

The problem, Kukla said, is people who wind up with the devices in their cars often don’t have any other option but to accept them.

“It’s lower income consumers, it’s folks with blemished credit who have trouble finding loans elsewhere. They really don’t feel like they have an effective choice of whether to take these devices or not,” Kukla said.

Conner said for those who think it won’t happen to them, “Who knew? You know, I didn’t know that this would happen to me. You know, so you don’t know until you’ve been there.”

Conner told CBS News she was unaware of it but admits there could have been some disclosure in the papers she signed when she bought the car. The dealership later sued the Conners for money they said they were owed. The couple’s attorney said the lawsuit was later dismissed.

We reached out to the dealership where the Conners bought the car, Car Credit City, several times, and finally were told by a representative that they weren’t interested.