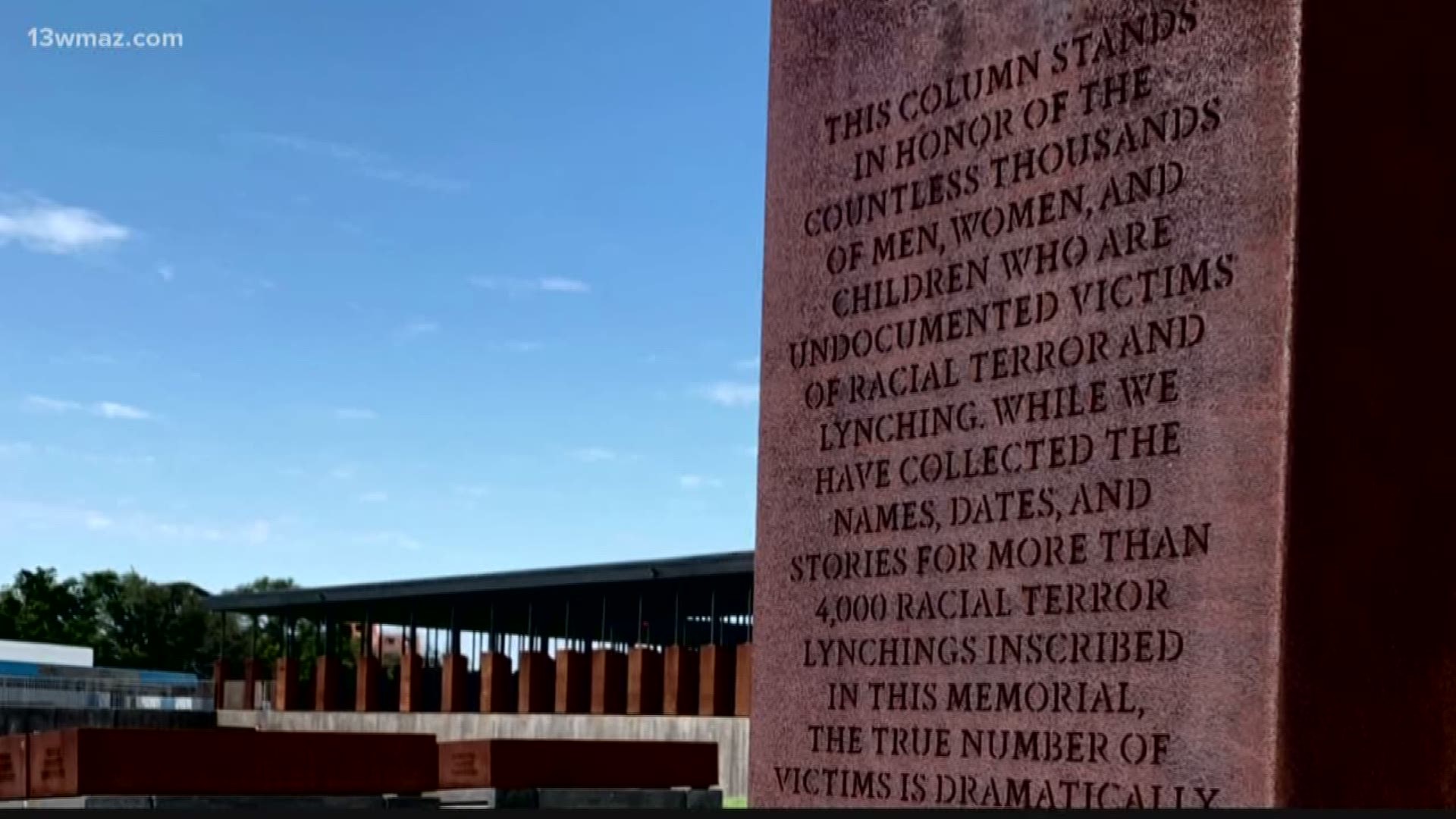

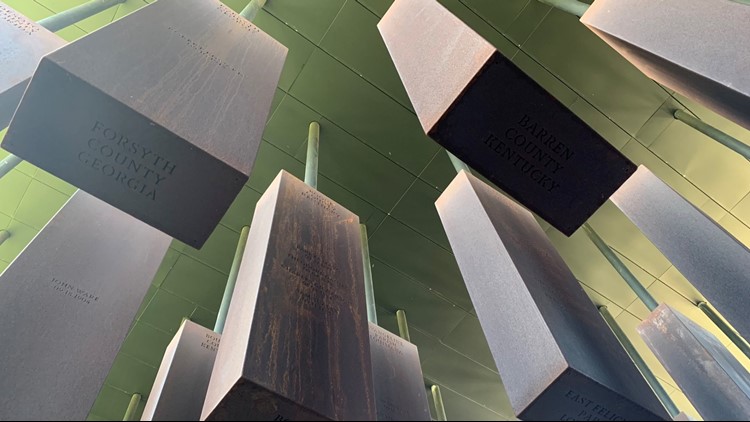

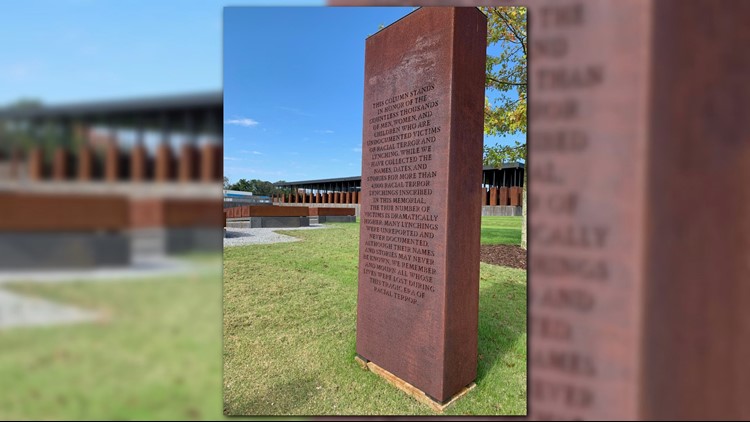

ATHENS, Ga. — Last spring, the Equal Justice Initiative opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, a sober site dedicated to documenting thousands of lynching victims across the United States.

One Georgia man helped provide hundreds of names recorded in that memorial. E.M. Beck is a retired University of Georgia professor who's made the study of lynchings his life's work along with a partner.

"What was a project became an obsession," Beck said. "When we got into it, what we found was that most of the sources of lynchings had a lot of inaccuracies, so we spent a lot of time putting together something we thought would be more accurate."

They thought that project would last six months -- it stretched on for two years and resulted in a published book, "A Festival of Violence." The book details a statistical look at lynchings in 10 states, and the reasons they may have been committed.

Beck and his partner, Stewart Tolnay, now keep a running list of lynch victims throughout the United States. Research is a daily practice.

"Every day, I do research," Beck said. "Even when I'm on vacation, if I've got internet connection, I'll spend an hour researching."

According to the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, more than 4,400 black people were lynched in the United States between 1877 and 1950. Beck extends that timeline from 1865 to 1980. The victims were brutalized in a number of ways, including hanging, burning and being riddled with bullets.

When Beck heard that the National Memorial for Peace and Justice was being put together, he was intrigued to see what the EJI had compiled compared to his own extensive research.

"I got their list, and I started checking against my list, and I was able to find that they did not have," Beck said. "I was able to find 300 to 400 cases that they didn't have."

One case in Beck's log is the Moore's Ford Bridge lynching of 1946, just 20 minutes from his Athens home. Two black couples were brutally beaten and shot by a mob in Oconee County after one of the men got in an argument with a white farmer.

"The mob stopped them and beat up the two men, drug the women out, drug all four of them over there and riddled them with bullets," Beck said. "There was never any indictments, there never will be any indictments. Everybody involved with it clammed up, and so it was just another tragedy that happened in the summer of 1946."

PHOTOS: Athens man's research on lynching leads back to Central Georgia

The lynching helped ensure President Harry Truman's commitment to civil rights. Beck helped with getting a proper historical marker placed near a highway a few miles away.

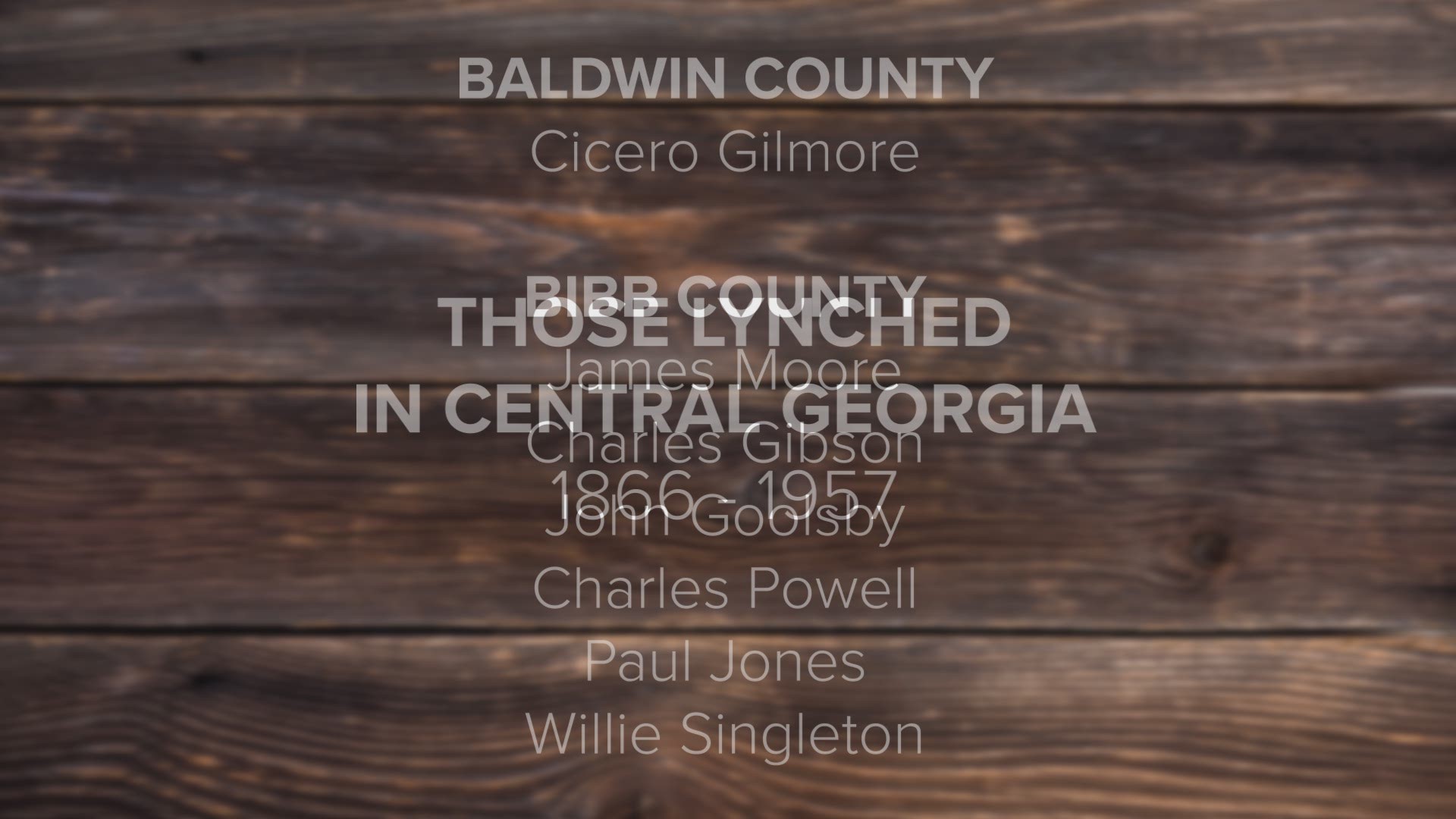

Central Georgia had a number of lynchings cases. According to Beck's data, 675 lynchings occurred in Georgia, 118 of those happened in Central Georgia. The southernmost counties were some of the worst offenders in the state.

Pulaski County lynched 10 black people between 1888 and 1957, Dooly County had 12 lynching victims between 1869 and 1935 and Dodge County held the highest total with 14 victims lynched between 1876 and 1919.

In 2016, a plaque was placed outside the Douglass Theatre in Macon, dedicated to 16 lynchings victims in Bibb, Jones and Monroe counties.

Many of the victims were accused of crimes like assaulting white women or murder, but proper justice rarely happened because mobs would take the law into their own hands. Other lynchings happened for things as small as disagreements.

"The primary purpose was to eliminate someone," Beck said. "But the secondary was, in fact, it reinforced especially in the case of white supremacy, it reinforced the notion of what white folks could do to black folks with impunity."

And at times that meant torture and desecration of black bodies, although Beck said that was more of the exception and not the norm. Typically, torture would happen with larger crowds that turned a lynching into a public spectacle.

"When you desecrate the body, then what you’re doing is -- not only did this person do something found that you want to kill them for, but you want to erase their memory, you want them not to exist," Beck said.

While Beck's data and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice document thousands of lynchings, there are still likely thousands that were never documented.

Those are stories that will not be told and people whose deaths are lost to history.