Criminal History: Anjette Lyles poisoned 4 family members for money

Some call her Macon's most infamous serial killer.

'Hard to imagine anyone killing people that they were supposed to love'

She was a small-town cook with a big time secret.

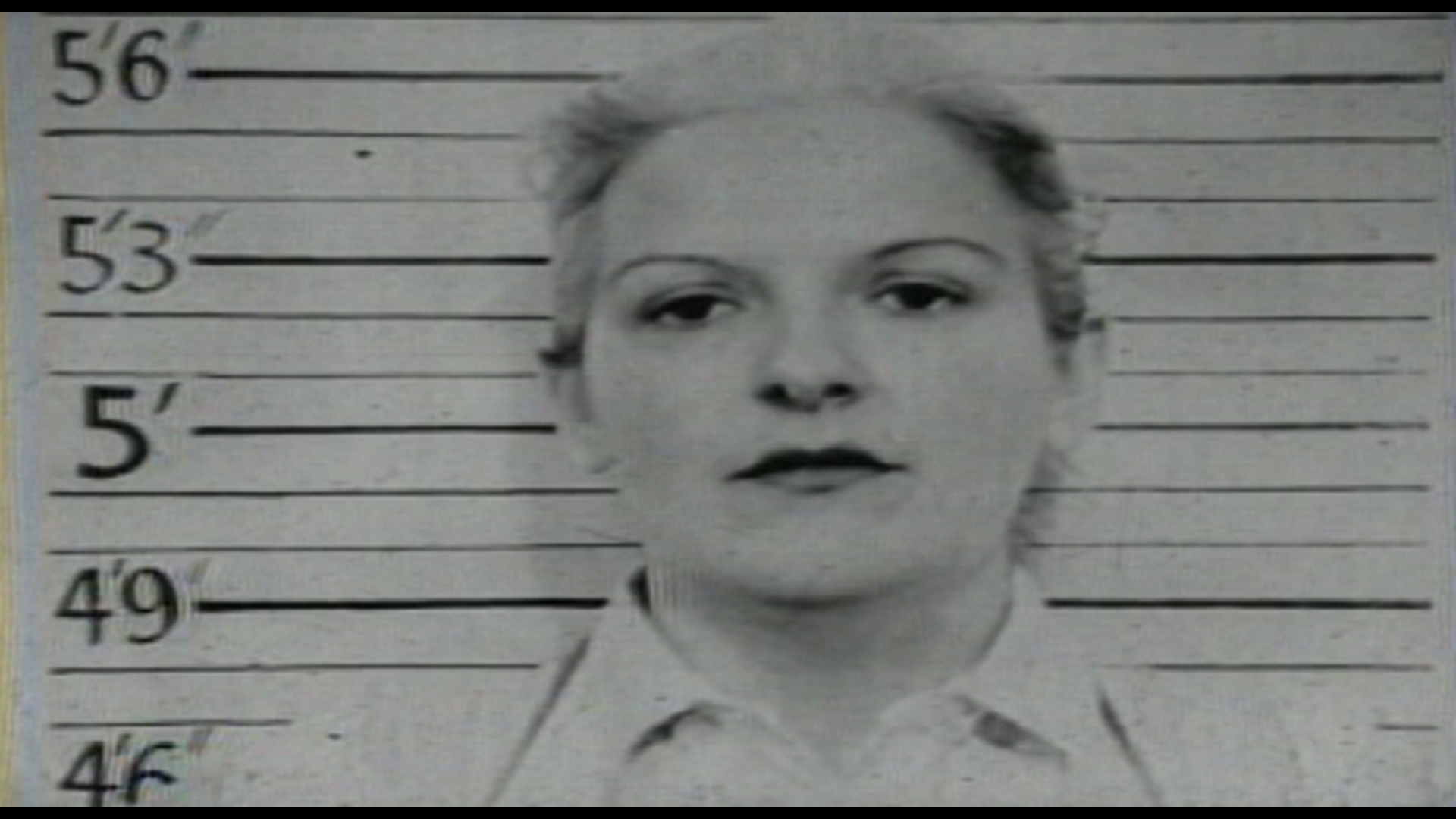

61 years ago, a Bibb County jury convicted Anjette Lyles of poisoning her 9-year-old daughter.

She was also accused of killing both of her husbands and her mother-in-law.

It's a bizarre case that's become the plot of books, plays, and TV specials. Decades later, it's still something that haunts some people in Macon.

"Macon, at that time, had a small-town vibe. People were very close," says longtime Macon resident, Patricia Sanderfer.

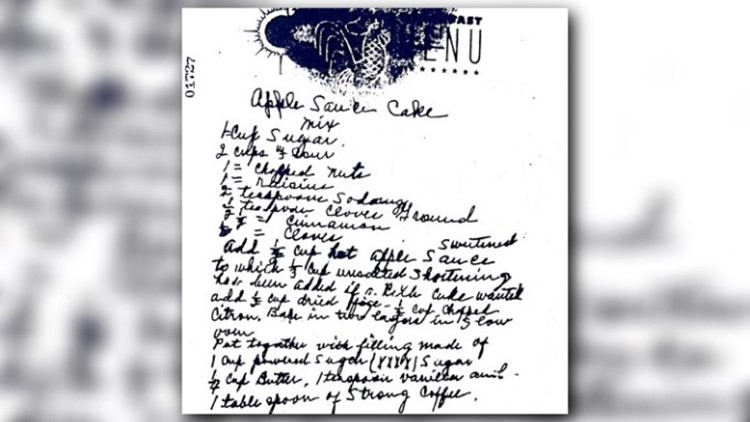

And at the center of the small southern town, there was a popular diner on Mulberry Street called Anjette's.

"Lawyers, attorneys, judges -- all kinds of folks -- would come and eat dinner at the diner," says Shannon Ray with Middle Georgia Paranormal Investigations.

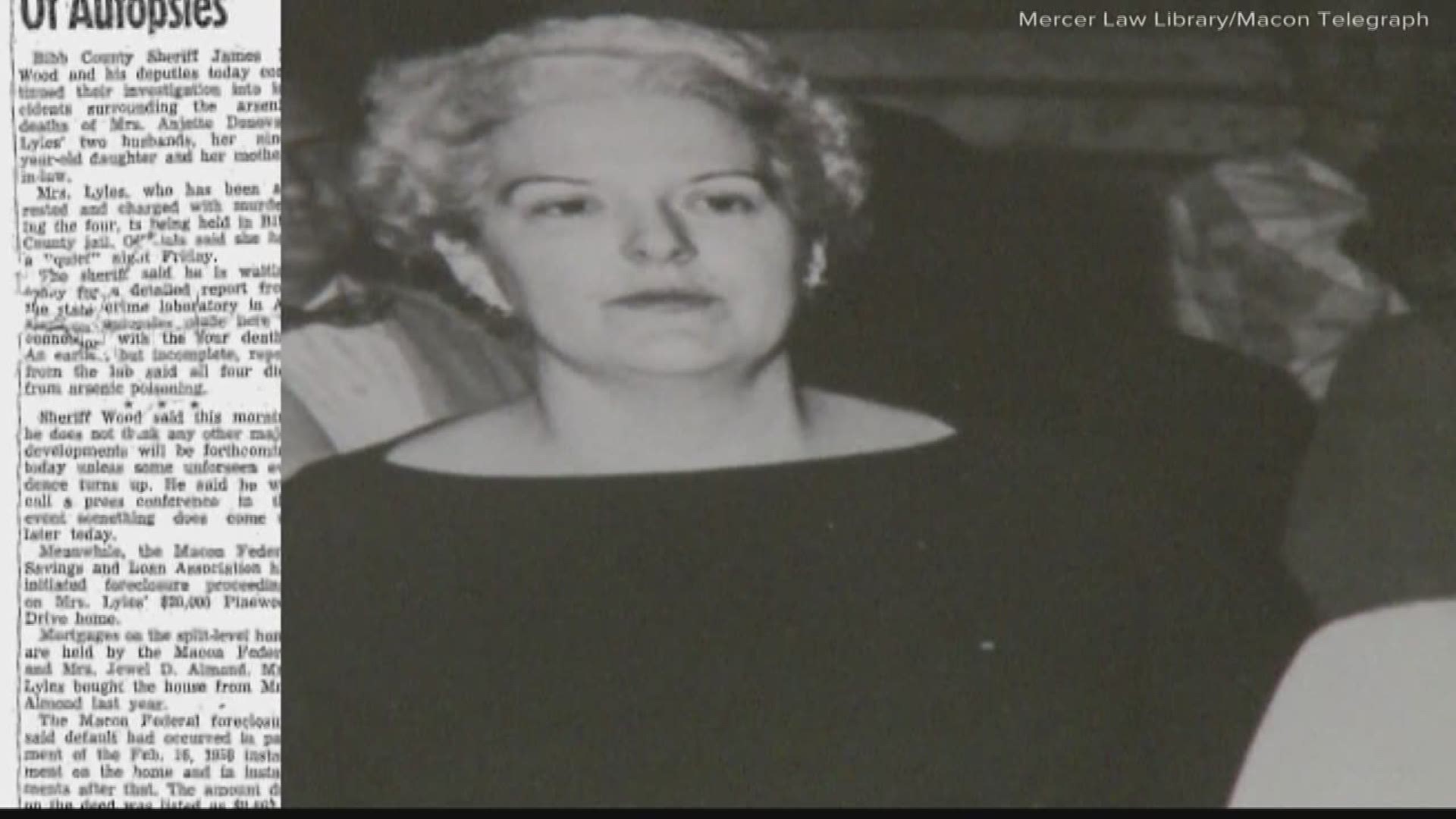

Owned by a buxom blonde with a personality to match, almost everyone in town knew Lyles.

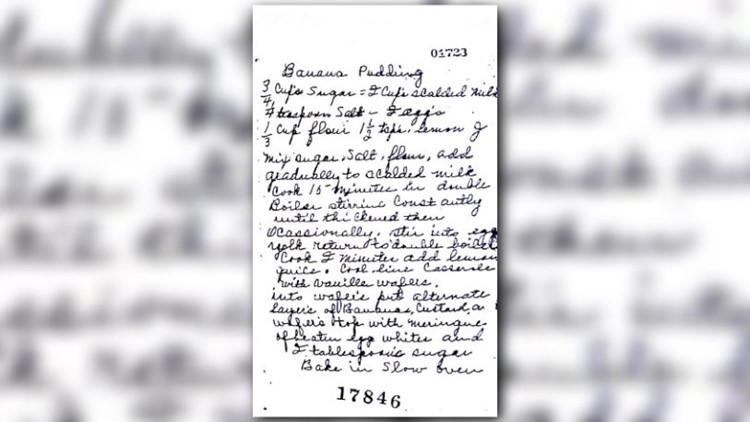

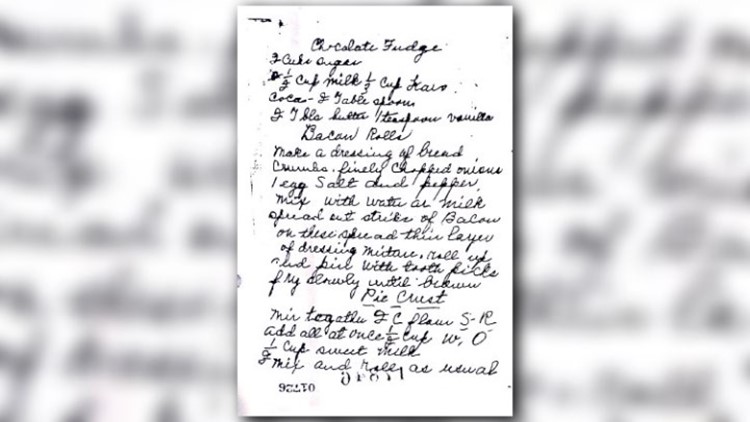

She greeted customers with tight hugs and warm conversation, an added bonus to her delicious southern fare.

"It was what we call 'country kitchen food' -- good, wholesome vegetables and meat -- just everyday southern food," says Sanderfer.

Between the fried chicken and mashed potatoes, it was a popular joint for many years, until people discovered murder might be on the menu.

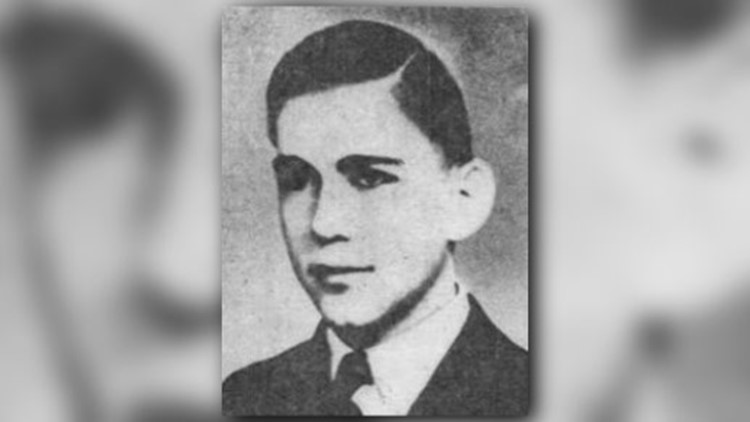

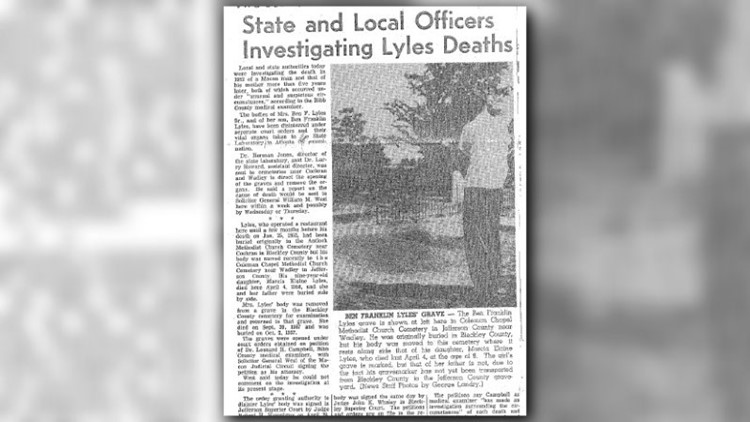

Over the course of six years, four of Lyles' immediate family members had died from what appeared to be natural causes -- her first husband, Ben Lyles, her second husband, Joe Gabbert, her mother-in-law, Julia Lyles, and Anjette's oldest daughter, Marcia.

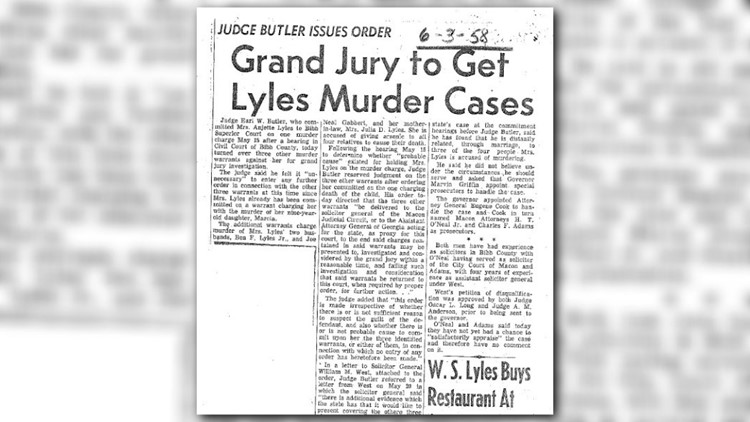

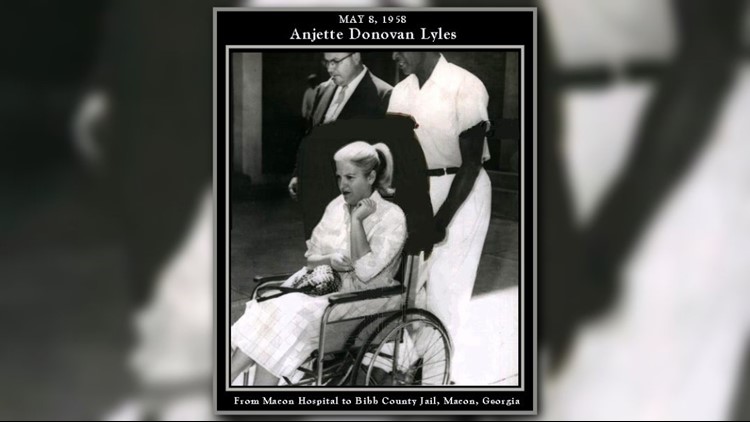

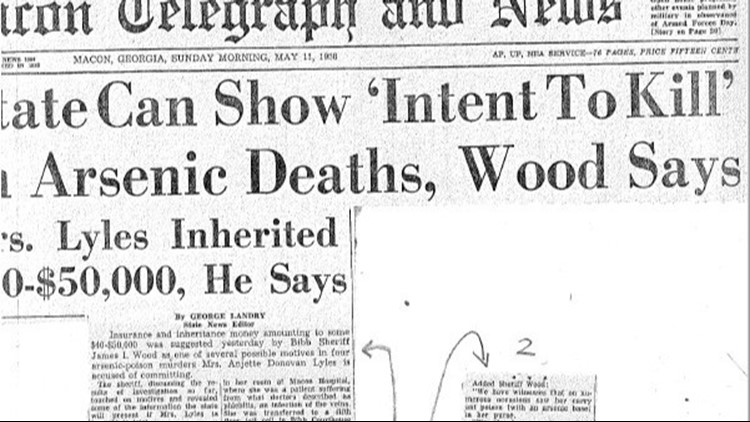

In May 1958, Bibb County deputies arrested Lyles and charged her with the murders of all 4 family members, but how had she done it?

"I was shocked, like everybody," says Sanderfer.

"To kill a 9-year-old child takes a very sociopath mind that goes beyond any pale of the imagination and narcissistic behavior," says Macon playwright Denver Pickard.

When investigators searched her home, they found voodoo paraphernalia, candles, potions, and powders, along with bottles of Terro Ant killer.

The pesticide contains arsenic, the same chemical found in the body of each of Lyles' dead family members after fresh toxicology tests.

"It was hard to imagine anyone killing people that they were supposed to love," says Sanderfer.

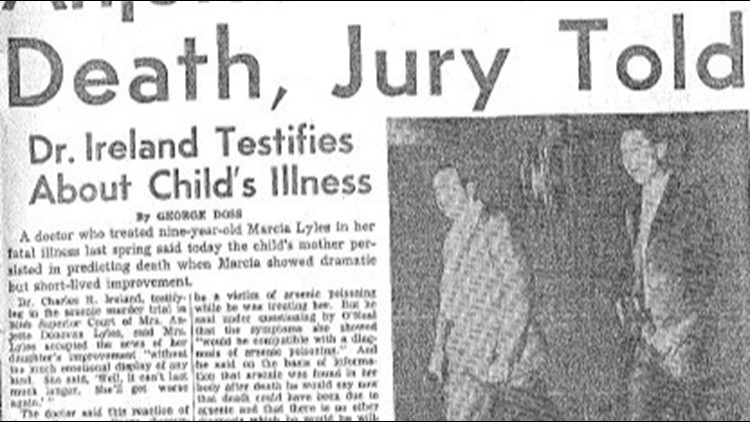

A medical examiner later testified that small doses of arsenic had been administered to all four victims over time, most likely disguised in food and drink.

"Well, how could she do that? Well, it was money. The root of all evil -- money," says Pickard.

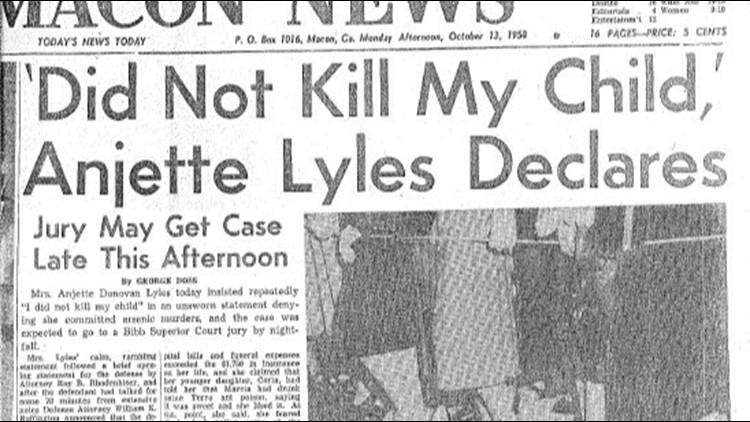

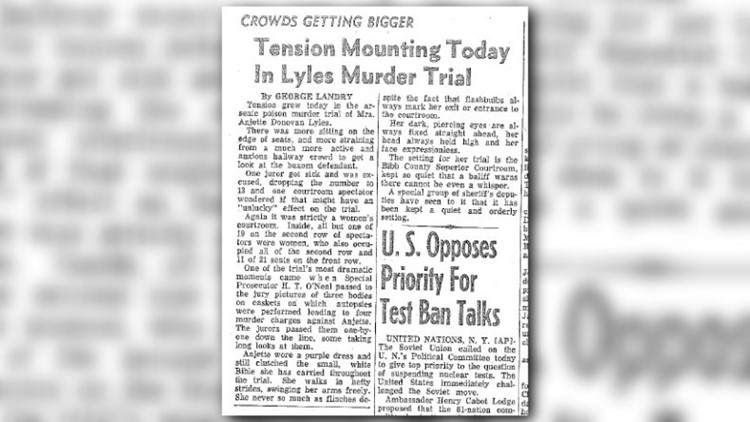

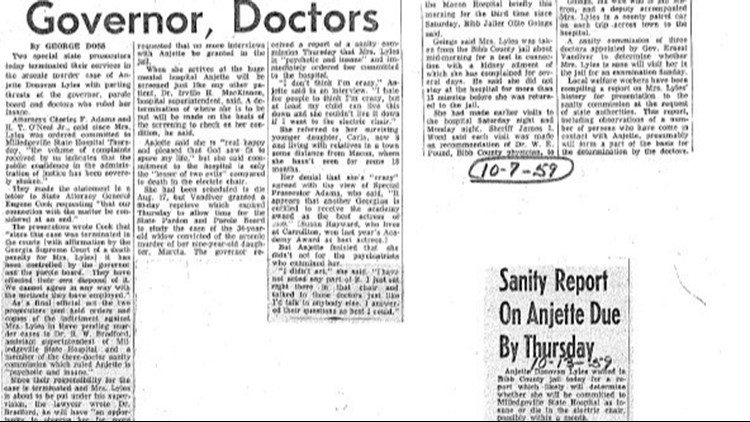

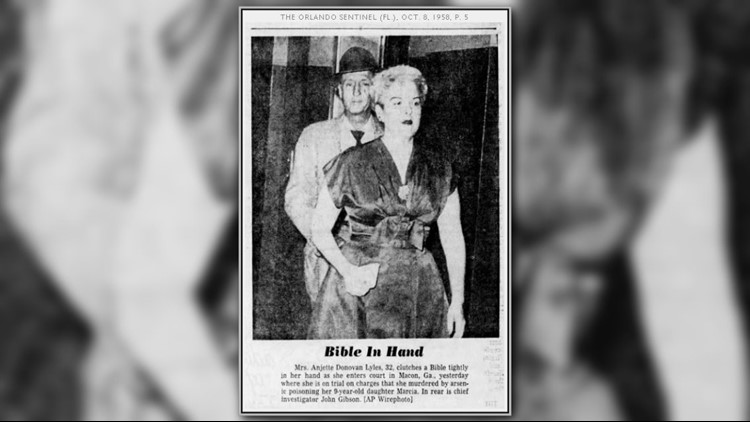

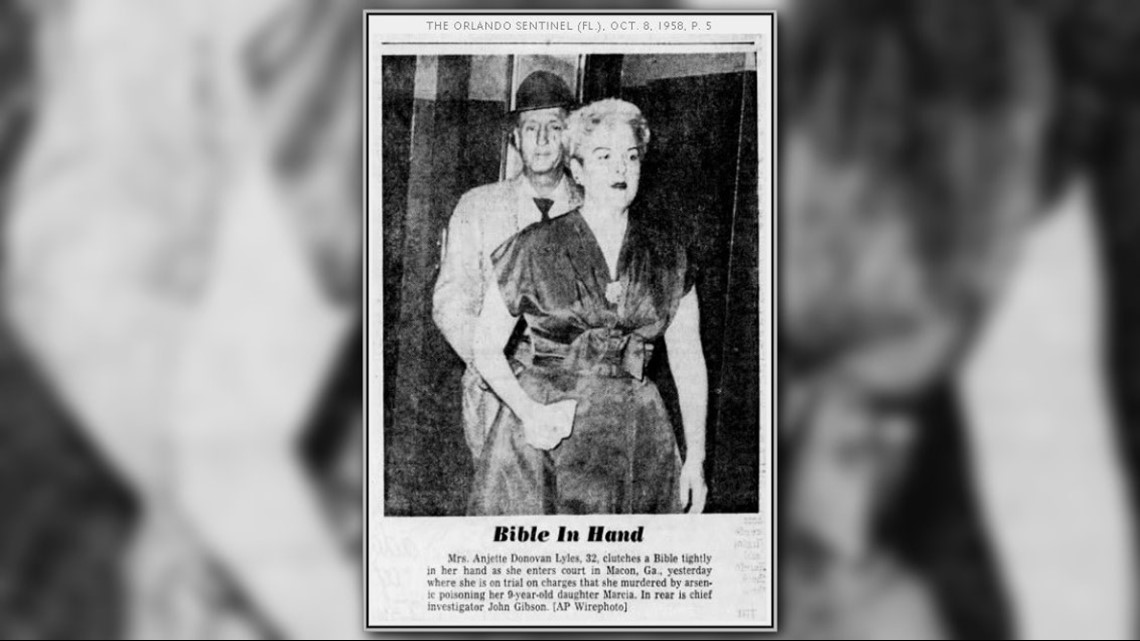

In October 1958, Lyles' trial began at the Bibb County Courthouse, drawing hundreds of spectators and reporters from around the world.

"Well, it was on the news and in the papers. It was everywhere. Many, many people were there," says Sanderfer.

Former state judge Bill Adams' father co-prosecuted the case in 1958, after the district attorney recused himself for being a distant relative of Lyles.

"This was a sensational trial, because Anjette was charged with murdering her daughter with arsenic poisoning," says Adams. "The theory of the case was Anjette was doing this for the money, for life insurance money."

During the week-long trial, the prosecution presented the jury with evidence that Lyles had spent money like, "a drunken sailor."

She reportedly bought herself a new white Cadillac with her second husband's life insurance payout.

"They were able to prove she had done some "funny business," if you will, with the way some of the insurance matters had been handled," says Adams.

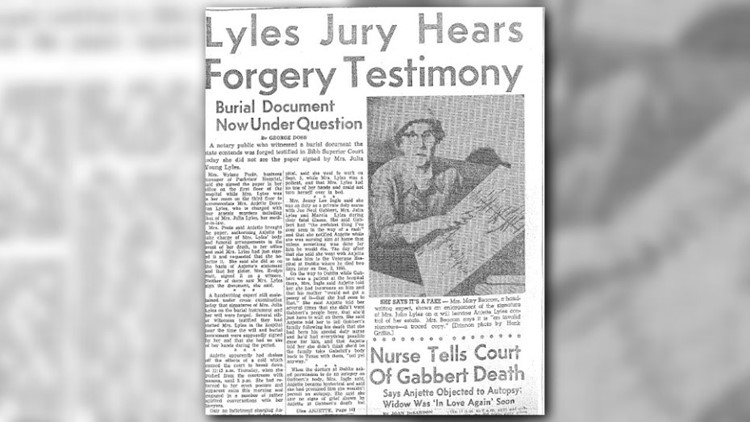

The prosecution also brought in a handwriting expert who testified that the signature on Julia Lyles' will had been forged.

"She thought she could charm the all-male jury into believing her when she said she did not do this," says Adams.

But, in the end, she couldn't.

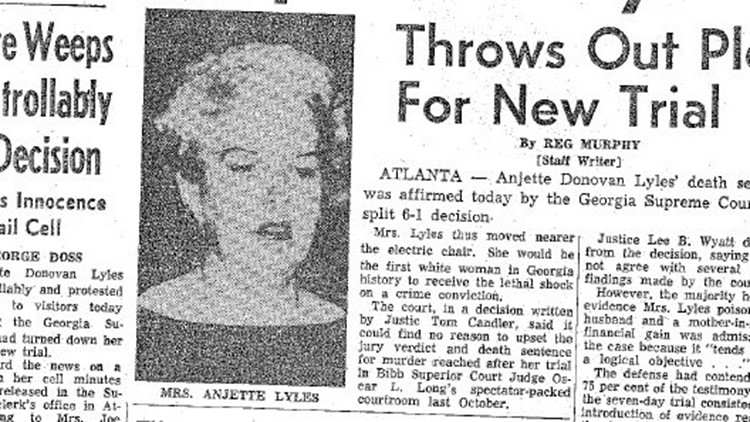

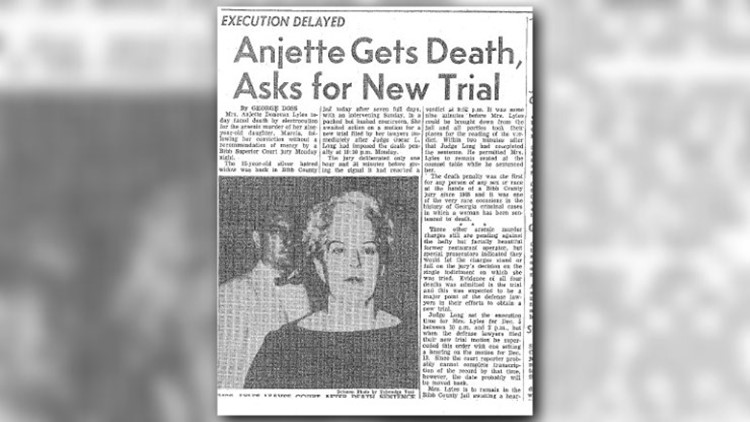

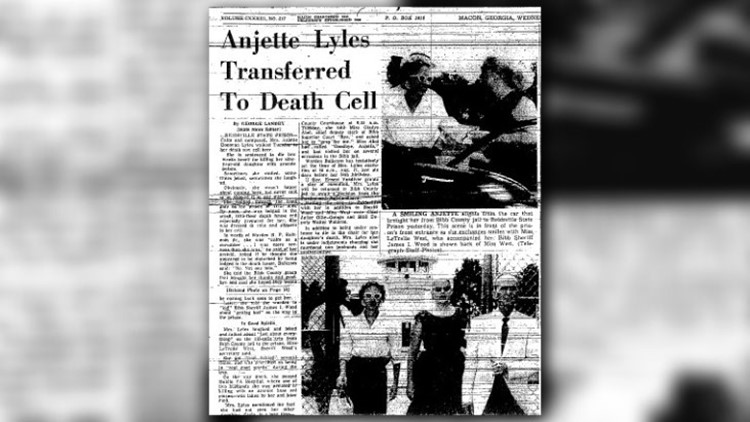

Anjette Lyles clutched her small, white Bible in a Bibb County Superior Court room and listened to the guilty verdict before being sentenced to death.

"She was never executed, though, because the governor, some said, did not want to sign a death warrant for a white woman," says Adams.

Visual history of the Anjette Lyles case

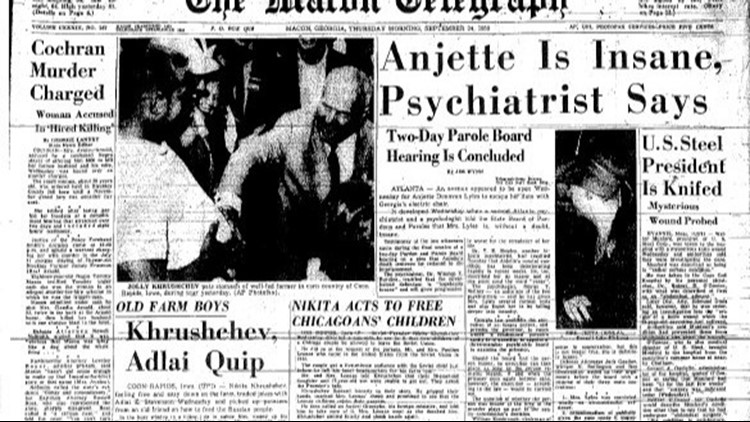

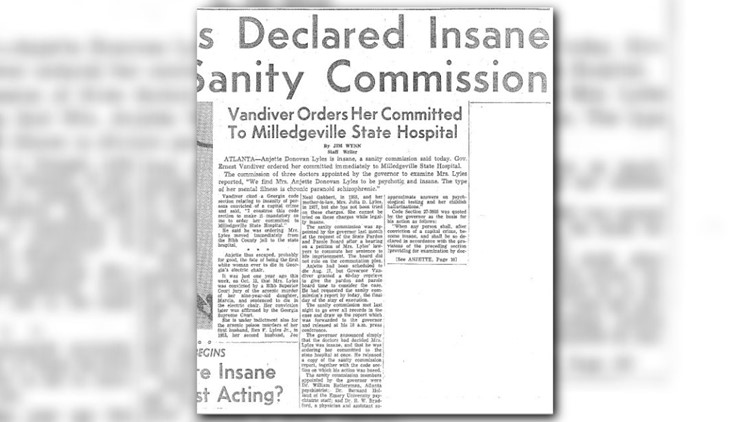

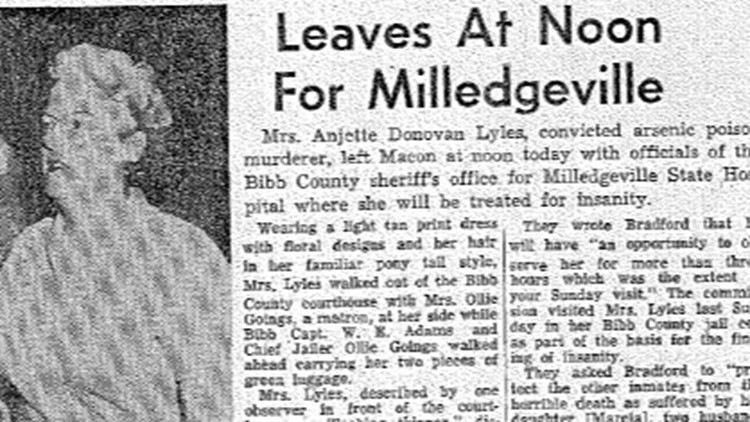

Lyles was later deemed "insane" by a group of psychologists, and spent the rest of her days at Central State Hospital in Milledgeville where people say, ironically, she worked in the kitchen.

"I feel like it's part of Macon's tarnished history that people don't like to talk about very much," says Ray.

In 1977, at age 52, Lyles died of a heart attack.

She and her first husband and daughter are all buried together at Coleman's Chapel Cemetery in Wadley, Georgia.

"Whisper to the Black Candle:" Deeper into the Anjette Lyles case

It's true that Anjette Lyles' case is one that has fascinated investigators as well as writers and storytellers for many years. One such writer is Jaclyn Weldon White, author of "Whisper to the Black Candle," a book that explores the Lyles case in great detail. If you are interested in learning more about this dark moment in Macon history, visit White's website.

MORE CRIMINAL HISTORY

RELATED: UNSOLVED: Who shot Tommy Purvis?

STAY ALERT | Download our FREE app now to receive breaking news and weather alerts. You can find the app on the Apple Store and Google Play.

STAY UPDATED | Click here to subscribe to our Midday Minute newsletter and receive the latest headlines and information in your inbox every day.

Have a news tip? Email news@13wmaz.com, or visit our Facebook page.